Inside Track: Johnny Cash | American VI: Ain’t No Grave

People + Opinion : Artists / Engineers / Producers / Programmers

Sometimes the simplest‑sounding music takes the most work to get right, and so it was with Johnny Cash's posthumous hit album American VI: Ain't No Grave. Engineer and mixer David R Ferguson was on hand at every stage of Rick Rubin's production.

Paul Tingen

David R Ferguson and Johnny Cash.David R Ferguson and Johnny Cash.Photo: Martyn Atkins

Hearing Johnny Cash singing the gospel classic 'Ain't No Grave (Gonna Hold This Body Down)' more than six years after his death is an arresting, evocative experience even for those who never knew the man personally. For those who knew and worked with Cash, the effect was even stronger. David R Ferguson, one of Nashville's most respected engineers and a long‑time collaborator with the singer, was lead engineer and lead mixer on the recently released sixth instalment of Cash's Rick Rubin‑produced American Recording series, American VI: Ain't No Grave. The engineer recalls: "John was gone and here he was singing 'Ain't No Grave' to us. When we started mixing that song, everybody on the project literally got goose‑bumps on their arms. It was really kind of spooky.”

The mix sessions took place in the spring of 2006, at Akademie Mathematique Of Philosophical Sound Research, no less — better known as Rick Rubin's studio in Los Angeles. They occurred at the tail end of several months of elaborate recording and mixing sessions, during which an extended team of engineers and musicians worked hard at framing a set of Cash vocal recordings. These recordings had been made in Nashville by Ferguson between May 2003 and Cash's death in September that year. Cash was 71 and had been diagnosed with dysautonomia a few years earlier. The disease had left him housebound, and to cap it all, in May 2003 his wife and partner of 35 years, June Carter Cash, had died. During his remaining four months, Cash was grieving, and with his health failing, he was aware that his time was limited.

Cash had found solace in recording during his last years, and also, presumably, in the iconic status he had achieved during the '90s. After his wife's death, his situation became truly desperate and he redoubled his studio efforts, recording the vocals for the songs that have been released posthumously on American V: A Hundred Highways (2006) and recently on American VI: Ain't No Grave.

Ferguson: "During the last months of his life, Johnny was recording a lot. It was almost an everyday thing. Johnny got sick, and then he got a little better, and it seemed as if playing and singing was the only thing that took his mind off his health problems. His hands were not working so great any more — he could not feel his fingers during these last months — and he could hardly stand that, because he wanted to play the guitar so badly. But he just couldn't do it. He played a little bit of guitar on the final track on the album, 'Aloha Oe', but other than that we focused on recording his vocals. There are two tracks on American VI that are just Johnny and his guitar, 'A Satisfied Mind' and 'Cool Water', and I had recorded these during the American III: Solitary Man period [2000]. Rick felt that they were really special and he waited for the right time to release them. He's a great record producer and he only releases things when he feels the time is right. In fact, when American V came out I was surprised at his track choices, because I thought that 'Ain't No Grave' and 'Redemption Day' would be on there.”

In The Middle

A young David Ferguson, far right, with Cowboy Jack Clement (far left) and country legends Johnny Cash and Roy Acuff, in a photo taken around 1988.A young David Ferguson, far right, with Cowboy Jack Clement (far left) and country legends Johnny Cash and Roy Acuff, in a photo taken around 1988.

'Ain't No Grave' and Sheryl Crow's 'Redemption Day' are arguably the stand‑out tracks on American VI, which is most likely why Rubin held them back for the final American release. Another reason may be that Rubin felt that 'Ain't No Grave' wasn't quite finished: as we shall see, the producer tinkered with Ferguson's final 2006 mix, adding some ear‑catching finishing touches. These additions occurred at the end of a long and winding road that took the tracks on American V and VI — simple, intimate and spontaneous as they may sound — from small‑scale recordings in Nashville to an extensive post‑production process in Los Angeles and, finally, to worldwide release. Ferguson explains the lengthy process, beginning, as they say, at the beginning.

"After June died, John briefly worked with their son John Carter Cash on a Carter Family tribute album, but soon afterwards we got back onto the American stuff. It was hard for John to get around, so we took the recording equipment to him. He might decide that it was easier to record in the round room in his house overlooking the lake, or we worked at his mother's house across the street, where we recorded 'Aloha Oe', or we recorded at John Carter Cash's Cash Cabin Studios. Everything was within a few hundred yards from each other. I would set up the equipment, and John or I would call his favourite musicians and we'd record. Rick came in for one of those sessions, and that really lightened Johnny's spirit. There was a great mutual respect between them.”

Another surprising aspect of the recordings for American V and VI is that, other than Cash's voice, very little of the Nashville recordings made it onto the final masters. Ferguson: "The whole point of the Nashville recordings was to get Johnny's vocals, the key and the tempo. Rick likes to be hands‑on with the tracks, so we later took the recordings to Los Angeles where Rick put on his own band. We changed the grooves of almost all the songs so dramatically that it did not work to use any of the original material. The Nashville process was to focus on recording Johnny singing with musicians he loved, and a few instrumental bits remain on the final albums, like Pat McLaughlin's guitar and Jack Clement's slide guitar on 'Aloha Oe': the original playing was really intimate, and you don't take Jack Clement's playing off anything! In Los Angeles we added a few things to the original instrumental tracks on that song.”

Producer Rick Rubin and the band outside his Akademie Mathematique studio. From left: Matt Sweeney, Mike Campbell, Benmont Tench, Rick Rubin, and engineer Dan Leffler.Producer Rick Rubin and the band outside his Akademie Mathematique studio. From left: Matt Sweeney, Mike Campbell, Benmont Tench, Rick Rubin, and engineer Dan Leffler.Photo: David R FergusonJohnny Cash sang very softly and preferred to be in the room with his Nashville musicians; this put significant demands on Ferguson's skill as an engineer. "I needed enough separation between Johnny's voice and the musicians, and the way you do that is by using close microphones and quiet instruments — there are no drums on this album, which made it much easier. Sometimes we would record the band and he would overdub his vocal, but that wasn't very often. Johnny had his own booth in the studio, but he didn't want to use headphones; he wanted to hear the real instruments and he really wanted to be in the middle of it. He was singing barely a whisper, so I close miked him and everyone else, put up some good windscreens and prayed! Nowadays with the new technology you can very easily erase all the bits in between the singing, and if you don't change the tempo later on, the ambient leakage will kind of disappear.”

All the 2003 Nashville material was recorded to Pro Tools, at 24‑bit/48kHz, using some choice mics and preamps. "I used a Neumann U67 on Johnny's voice for most songs, in some cases a U87, and occasionally an AKG 414. It would depend on what room we were recording in. The mic then went through an Urei 6176 mic pre, and then directly into Pro Tools. That was it. I didn't use any limiters or compressors. In the past I'd also sometimes recorded Johnny at his house in Jamaica, where I recorded to a Roland 2480 and used the same mics and mic pres — it was like I carried an aeroplane full of stuff there — but I'm not sure how much of that ended up on these records.”

Time‑consuming

Two years after Cash's death, Rubin decided to prepare the 2003 material for release on what would become the American V and VI albums. So, late in 2005, Ferguson travelled to Rubin's Akademie Mathematique Of Philosophical Sound Research, where he joined an extended team. Rubin had invited a band consisting of renowned players like guitarists Mike Campbell (Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers), Smokey Hormel (Beck, Tom Waits), and Matt Sweeney (Dixie Chicks, Neil Diamond), plus keyboardist Benmont Tench (Heartbreakers, U2, Dylan) into the studio, with guitarist/keyboardist Jonny Polonsky occasionally coming in to add his talents. The posse of engineers present included Greg Fidelman, Dan Leffler, Phillip Broussard and Paul Fig.

Ferguson: "A lot of people are involved in making Rick Rubin's records, so I don't want to act like I was the big hero. I was the lead engineer and mixer, but that doesn't mean shit. There were some really great seconds on this album, guys that have worked for Rick in the past quite a lot. Dan Leffler is fantastic, and so is Philip Broussard, and Greg Fidelman is a world‑class engineer and mixer. There was so much mixing to do on those last two records, and we had been working on the project for so long, that we got into a time crunch towards the end, and took over another studio where Greg mixed a few of the tracks.”

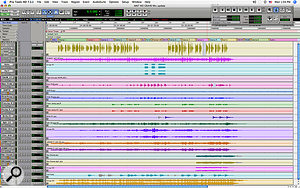

The recording team sat the band in one of the recording areas at Akademie Mathematique Of Philosophical Sound Research for extensive overdubbing sessions. Ferguson: "We had the band in a circle in the same room, while Benmont's B3 was out in the hallway and his Leslie in the garage, so they were isolated and we got a really good sound from them. Jonny Polonsky wasn't there for all of the tracking, he overdubbed a little bit of everything. We started off with a click and Johnny's vocal in their headphones, and Rick sitting at the Neve console and guiding the band, with regards to the kind of feeling or mood that he wanted them to set. We then did a lot of different takes. One of the reasons these records take so long to make is that you afterwards have to listen to every note of every take and choose the best bits and compile them. That's a time‑consuming and, at times, confusing process. Eventually, when we were done editing the stuff, we consolidated the tracks to make sure nothing got accidentally moved around. That's the reason the [Pro Tools] Edit window for 'Ain't No Grave' looks so tidy!”

'Ain't No Grave'

Traditional

Produced by Rick Rubin

There are 19 instrumental tracks, one vocal track and one SMPTE track on the 'Ain't No Grave' Edit window.

This Pro Tools screen capture shows all of the tracks that were actually used on the mix of 'Ain't No Grave', apart from Rick Rubin's last‑minute overdubs. This Pro Tools screen capture shows all of the tracks that were actually used on the mix of 'Ain't No Grave', apart from Rick Rubin's last‑minute overdubs. Ferguson takes it from the top, explaining what's what and how it was recorded. "The click track and some of the Nashville tracks are actually above the vocal track at the top, but you can't see them on this screen shot. The vocal track itself is called 'New Vocal RR' because it's a new vocal edit, and RR means it has Rick's approval. A lot of the vocal and other editing was done by other engineers, like Greg and Dan in another room. Editing is not a big enough word, because there's a real art to it, and Greg is one of the best in the world. Johnny's vocals were compiled from two or three takes, and Greg was still editing and, where necessary, tuning the vocals even while I was already mixing, and I then laid them where Rick wanted them. There may have been tiny timing issues, and that was a question of going into the waveform, highlighting things and manually nudging them, going on feel. You don't want things to sound robotic.

"The track below the vocals is Smokey Hormel's acoustic guitar. I recorded all the acoustic guitars with Neumann KM64 microphones, and sometimes a KM84. I remember because I use these microphones all the time! The mics were going straight through Rick's Neve 8068 board, which sounded great. I just recorded everything flat, no effects or treatments going in. You place the mics so that you get the sound you want, and then you can doctor it afterwards. Below the guitar track are two really great keyboard parts, played by Jonny Polonsky on Conn and Farfisa organs. Rick wanted something in the instrumental part, and Jonny overdubbed these solo‑ish parts after the band had laid down the basic tracks. I recorded the organs with Rick's Neumann KM184 mics, again through the desk.”

The next track may raise some eyebrows, and Ferguson laughed: "Yes, it's tape hiss. Let me explain that to you! From time to time I use that. It's subliminal in analogue, and it helps your ears to get used to digital. Tape hiss really helps to disguise edits. Also, when somebody stops singing, the air around them changes. With Johnny singing so softly we left the room sound where we could, but in some cases, when there was leakage, we had to insert silence when he wasn't singing. Tape hiss helps to mask these things. It's one of my tricks, and I think most of the tracks on the album have tape hiss on them. This may sound like I'm full of shit, but it seems to work! It really does take the edges off edits. The best way to get tape hiss is to use biased tape, because it sounds different when it's biased. You find some biased tape, you play it, in my case at 30ips, record a few minutes into your DAW, and bring it up a little bit in the mix.

The band at work in Akademie Mathematique. Smokey Hormel is closest to the camera, Mike Campbell behind him and to the left, Johnny Polonsky is at the rear and Matt Sweeney right.The band at work in Akademie Mathematique. Smokey Hormel is closest to the camera, Mike Campbell behind him and to the left, Johnny Polonsky is at the rear and Matt Sweeney right."Below the tape hiss is a bass slide track, which was played by Smokey on an acoustic‑guitar‑shaped acoustic bass — the guys switched around on instruments a lot. I recorded that with the KM64 and again via the Neve, no compression. Smokey was a genius in coming up with that part, because it makes the track a little bit more spooky. We then re‑amped the slide bass part via an old Fender Pro Bassman from the '50s, which I recorded with an SM57. On loud guitar amps I always use that mic. I laid down the re‑amped slide bass on a separate track, below, and in between is a SMPTE track for the Massenburg Flying Faders automation on the Neve desk. Going further down there are two piano tracks, credited to Jonny, but that could be labelled wrongly, I think Benmont played that. Rick's grand piano is upstairs, and I used two Royer R121 ribbon mics on it, again going straight into the Neve.

"I added the bells. There are these cathedral bells in Rick's place, six feet high and six feet wide, and Dan Leffler and I tried them out and recorded them with a U67 — when recording cathedral bells you need to use a wide‑pattern microphone! The electric guitar was played by Matt Sweeney, and that probably went through the same Fender Bassman amp and again the SM57. Matt also played a National electric dobro, which I again recorded via the Bassman, and with two SM57s to get a left and right stereo part. Then there's Jonny's acoustic, which is a 12‑string part, recorded with a KM64 or 84. You can see that I duplicated that part below, which I sometimes do to get a part in stereo. I'll duplicate and it and offset one of the parts seven milliseconds and then pan them wide. Why seven? I don't know, it seems the right amount for me. It's enough to make something appear stereo without it sounding like delay, and also enough to avoid strange things with the phase. Seven milliseconds seems to work for all instruments. It's probably a big no‑no to 'stereoise' something in this way, but for me there's no right or wrong. Whatever it takes to get it done. Below that are two Chamberlin oboe tracks, DI'ed into the desk and grouped on a track below; and finally a Wurlitzer, played via the same Bassman for some distortion, and recorded with the same SM57. At the very bottom is stereo mix number nine, which is the last one we did, but not necessarily the one used.”

Creating A Mood

Some material for albums in the American series was recorded by Ferguson on a portable rig at Johnny Cash's house in Jamaica. Some material for albums in the American series was recorded by Ferguson on a portable rig at Johnny Cash's house in Jamaica.

Ferguson is reluctant to make an estimate of how much time was spent recording and editing 'Ain't No Grave', because they sometimes worked on several songs at the same time, but his rough guess was 10 days in total. For the same reason, his estimate of the time the final mix took, two or three days, is also approximate. "I can't tell exactly. But it took a lot of time. You might spend five or six hours recording music, and then you add overdubs, and then you fool with it and massage it, and gradually you turn it into a painting. One issue was that Rick had to approve everything and he also needed to hear each of the different mixes we attempted, yet he wasn't always there. Sometimes he was away producing Linkin Park or the Red Hot Chili Peppers. He would listen to our work either in his room upstairs or in his house in Malibu, so I'd either show up with a CD or I'd send him the track via Internet in full resolution, and he'd listen to it on his $50,000 speakers! Of course, Rick also had to get into the right frame of mind to be able to judge something as intimate as this. So sometimes we'd wait for his approval, and we might work on something else meanwhile. Rick has a really great memory, and he may say, 'I remember that there was something different going on in this song at this point,' and you go back and listen, and he's right. So there was a lot of to-ing and fro‑ing. But usually when Rick says a mix is done, it is done, and you don't have to worry about it any more, and you can move onto another song.

"I mixed on his 32‑channel Neve 8068, because I prefer mixing on a console, and because it's how Rick's studio is set up. I'll mix in the box if I have to, but Rick's Neve sounds great, and also, I prefer to stay away from plug‑ins and use the real thing. Outboard still sounds better. It just does. I use plug‑ins from time to time, and I use them in my own studio in Nashville, the Butcher Shoppe, because I don't have a lot of outboard. But if you can afford the real thing, use it. Some plug‑ins do things outboard can't, like you can do some very precise EQ with plug‑ins, but at the same time things easily start splattering and getting sibilant with plug‑in EQs and limiters. There's nothing like a great real limiter, and when they do their job properly, you can't even hear them working. Limiters are like cars, you get what you pay for!

"With regards to waiting for Rick to come back to us while we were working, Flying Faders turned out to be very handy, and Dan Leffler is a master at documenting the board and bringing a mix exactly to where it was. In some cases we had small sessions with only six returns, and we'd simply use another part of the Neve to continue with tracking.

"The tracks on the American albums sound very simple, but mixing them was a lot more involved than just pushing up the faders. Normally, when mixing I start with the drums, and then add in the bass, and then so on, and mainly you're looking for the groove. Often, when you're in a studio recording a band and monitoring them, the groove is there. And then you go back a week later, and you pull up the session and sometimes it's hard to find the groove. It's like: 'Where the hell is it gone?' It's all about the blend. So, with the mixes for American V and VI, I would initially start off with the guitars or whatever has the groove, and go from there. But when I started doing these mixes, Rick kept saying: 'Turn the ocal up, turn the vocal up.' This struck me, because there are several different pockets that the vocal can go in when mixing. There's a pocket way back and thinned‑out that makes the band sound louder, and then there's the next one, which makes the band sound a little softer. But these tracks were all about the vocal. It's all about creating a mood, and Johnny Cash's vocals are the loudest thing on the record.”

The Vocal Is The Key

Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: David R Ferguson

"John's vocal chain was the key. His voice wasn't really strong, so I had to pump it to make it as strong as I could make it sound, and to give the impression that he sang out more than he did. So I put his vocal through a Fairchild 670 limiter and then through the Massenburg GML EQ and then back into the console. It depended on the song, but I tended to hit the limiter really hard. Sometimes, if I could hear things pump with one limiter, I'd send it through a second one and it went away. On earlier records, I used the RCA BA6A limiter on John's voice, but I fell in love with the Fairchild. Also, digital is not the warmest medium in the world, and I was trying to warm things up as much as I could. The EQ boosted around 4kHz. I recall Rick saying that it needed to be 'brighter but not brighter' — so more of the low highs, and no boosting around 8 or 10 kHz, because then things can really start to splatter. The 3/4/5k range seemed to make things jump out a little more.

"Getting Johnny's voice to sound great was the most important thing, and after that I got a groove going with the acoustic guitars, and then brought things in as we needed them. The way Rick makes records is to build things, as far as dynamics go. You build it up, take it down, and build it up again. We tried to create a good mood for this song, and I used console EQ and [Universal Audio] 1176 compressors on probably every instrument, and that was it. There's no reverb on any of the tracks. Every time I've tried to put a reverb on a record for Rick, he says 'take it off.' It was hard for me to get used to, but it makes a lot of sense. We used a reverb chamber at Capitol for 'The First Time I Ever Saw Your Face' [on American IV: The Man Comes Around, 2002], but that's it.

"I'd have made the acoustic guitars pretty bright, because the guys didn't like changing their strings, and I also rolled out around 100Hz, to make sure it didn't get boomy. I had the Bomb Factory BF76 [plug‑in] on the slide bass, as well as the Neve 33609 limiter, and I may not have used the re‑amped track. I think I had the same stereo Neve 33609 on the Farfisa and Conn organs. I used that Neve limiter on a lot of the solo instruments. I also had a Moogerfooger plug‑in on the bells, because they were so in tune, you could hardly hear them. A phasing effect added a little wobble, and you could hear them a little better. When I mixed in the bells the track really started sounding spooky! I can't recall all of what I did, because it's a few years ago, but mainly it was simply a matter of fitting the instruments together, and EQ'ing without soloing. Sometimes you have to solo, of course, but it's a good idea to EQ with the instrument in the track, because in that way it makes more sense. If something sounds good solo'ed, it doesn't mean it fits.

"Finally, I mixed to half‑inch, and put the Fairchild 670 over the two‑mix. That works really well, especially for more sparse recordings. Putting a limiter over the two‑mix in the right way will help the mix because it's not squeezing everything together. Instead it will bring the band up when the singer isn't singing, so you can have the vocal really loud, and when there are no vocals the band comes up a little. This really helps your mix. If it's working right, you get a really nice smooth transition, and a $50,000 Fairchild does a good job! For editing different mixes together, which was done by Philip Broussard, we transferred the mixes back to Pro Tools, and we'd then send the half‑inch tapes and the Pro Tools edits to the mastering engineer [Stephen Marcussen], with the regions showing on the tape so he knew exactly where to edit. Rick then decided what to use, and whether the aged half‑inch tapes sounded better than the digital copies. Once half‑inch sets, even just for a week, the sound starts to change. In fact, the sound on tape changes all the time, it never stops. You may get print‑through, depending on how hot you recorded, magnetic rust touches, and your mix may begin to sound a little cloudy. So we always make a digital copy at the time a half‑inch mix is printed, to compare.”

The Final Touches

David R Ferguson.David R Ferguson.

Clearly, an astonishing amount of attention to detail went into the creation of American V and VI. This is also illustrated by the events of late 2009, when Ferguson received a call from Rubin requesting him to come over to LA and dig out the 2006 mixes for the forthcoming albums. "I went through all the half‑inch mixes and took them to Rick's Malibu house. When I played him 'Ain't No Grave', he said: 'That's not the one. We have a better mix than that!' He's usually right, and he was. He's not as close to the whole thing as the engineer or the mixer: he keeps his distance, and that means he can listen without thinking about the process, which is great. He was working with the Avett Brothers at the time, and once I got him the mix he wanted, he and engineer Ryan Hewitt overdubbed a banjo, chains and footsteps to my mix of the song. That's really hard to do, but they did a great job.”

The addition of the banjo, chains, and footsteps were a stroke of genius that concluded an astoundingly intricate, six‑and‑a‑half year long, off‑and‑on gestation process. It greatly enhanced the goose‑bump factor of the album's title track, and the sense of the spirit of Johnny Cash being kept alive. Ain't no grave gonna hold him down, indeed. .

David R Ferguson

David R Ferguson was born in 1962 in Nashville, and by his own account "always wanted to become an engineer”. He got his break in 1980 working as an errand boy at the legendary Cowboy Jack Clement's Cowboy Arms Hotel and Recording Spa studio in Nashville. "I'd sneak up into the studio at night and learned how to use the equipment, and after I'd done that for a year or two I made a record while he was out of town. He came back and listened to that record 100 times, and finally summoned me to his office, and asked me whether I'd made it. I admitted I had, and that I'd recorded it in his studio. So he said, 'You're fired! But I'll hire you back as my engineer.' After that, I recorded a lot of records, and Jack also put me through two schools, Nashville Tech and Belmont, to take courses in engineering.”

Ferguson, who adds that he learned most of his engineering skills from engineer Jack 'Stack A Track' Grochmal, worked for many years at Clement's studio, clocking up an impressive list of credits that includes U2 (on their 1987 Rattle & Hum album) and, naturally, Johnny Cash. "I first met Johnny in 1982, via Jack. A couple of weeks after that, Johnny wanted me to help him put some work tapes together for publishing purposes. That was the first time I recorded him. Johnny was a great man, one of the few great men I've ever met, and I always treated him so. At the same time, he didn't like to be with a lick‑ass, so I also treated him like a friend and a person, and he appreciated that. We became buddies and I often travelled with him.”

Today Ferguson co‑owns, together with John Prine, a studio in Nashville called The Butcher Shoppe. He spends much of his time working there, with second engineer Sean Sullivan. Ferguson can be reached at thebutchershoppe@bellsouth.net.

No comments:

Post a Comment