Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions. Where there are no limits! Enjoy your visit!

Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions

| Company Founded | 2005 |

|---|

| Overview | Our services include Sound Engineering, Audio Post-Production, System Upgrades and Equipment Consulting. |

|---|---|

| Mission | Our mission is to provide excellent quality and service to our customers. We do customized service. |

Saturday, February 28, 2015

Friday, February 27, 2015

Q How do I tackle the unwanted noise coming from analogue modelling plug-ins?

Sound Advice : Recording

I like to use a lot of analogue modelling plug-ins when I’m mixing, but while I like the sounds I’m getting in general, I always seem to end up with too much noise and it’s driving me crazy! What’s the best way to tackle this problem?

Daniel Jones via email

SOS Reviews Editor Matt Houghton replies: The noise could be coming from more than one place, and could be being amplified by more than one processor, so the first task is to find out where the noise is actually emanating from. Step one is to turn off the noise generators! These seem to be on by default in too many modelling plug-ins. (Really, who wants them to sound that authentic? They’ll be making them break down during sessions and charging a virtual repair fee next!) Step two is to go back and look at the sources you’re processing, to see if there’s any low-level noise there that’s being amplified by the compression make-up gain that’s going on in a lot of these plug-ins. I’m not just talking about compressors and limiters, here — anything that features some sort of saturation or distortion will reduce the dynamic range, and when gain’s applied that will bring up the noise along with everything else.

A common cause of unwanted noise is analogue-modelling plug-ins, which are often too authentic! This UAD Studer model, for example, features a noise control which, by default, is hidden beneath a panel. Several Waves plug-ins also have noise switched on by default, and in some mixes compression and limiting further down the signal chain can raise this to annoying levels.A common cause of unwanted noise is analogue-modelling plug-ins, which are often too authentic! This UAD Studer model, for example, features a noise control which, by default, is hidden beneath a panel. Several Waves plug-ins also have noise switched on by default, and in some mixes compression and limiting further down the signal chain can raise this to annoying levels.Then it’s time to consider how to tackle the remaining noise. If noise is prominent while the wanted signal is playing, consider using a dedicated noise-removal tool like iZotope RX, Waves X-Noise and so on. These can be highly effective, but they’ll sometimes leave unwanted artifacts. If the noise only bothers you between sections of wanted sound, then level automation on the individual sources is an obvious solution — if the noise isn’t there, it can’t be amplified by any plug-in.

Gates do this automatically, of course, but they just don’t sound right to me unless they have a variable ‘floor’ control, or whatever you prefer to call it (the bundled one in Cubase, for example, doesn’t have this feature), as the abrupt cutting off of the noise just serves to draw attention to the fact it was there in the first place. I’d rather have noise right the way through than hear that! But even then, level automation is a more precise option.

A more natural-sounding technique than a gate is to automate the frequency of a low-pass filter so that the filter rolls down the spectrum in sections between the wanted bits of sound. The sound remains, but it is less noticeable, and the transition between sections is less glaring too. This is how the old Symetrix noise gates worked, and where sophisticated noise-removal tools such as iZotope RX aren’t called for, or aren’t working for you for whatever reason, it’s a useful technique to try on hissy guitar sounds; I’ll bet it will work for you too.

I haven’t yet found a plug-in that does this automatically for you, but you can do this in Cockos Reaper using its dynamic automation system (it’s called Parameter Modulation; see http://sosm.ag/reaper-parametermod for details). This can be set up to make the filter frequency move dynamically in relation to the amplitude of the source signal — so as the vocal phrase finishes, the filter rolls off the more noticeable high-frequency hiss. It takes a bit of finessing to get it right, but if you’re already using Reaper, it could be just the ticket!

I like to use a lot of analogue modelling plug-ins when I’m mixing, but while I like the sounds I’m getting in general, I always seem to end up with too much noise and it’s driving me crazy! What’s the best way to tackle this problem?

Daniel Jones via email

SOS Reviews Editor Matt Houghton replies: The noise could be coming from more than one place, and could be being amplified by more than one processor, so the first task is to find out where the noise is actually emanating from. Step one is to turn off the noise generators! These seem to be on by default in too many modelling plug-ins. (Really, who wants them to sound that authentic? They’ll be making them break down during sessions and charging a virtual repair fee next!) Step two is to go back and look at the sources you’re processing, to see if there’s any low-level noise there that’s being amplified by the compression make-up gain that’s going on in a lot of these plug-ins. I’m not just talking about compressors and limiters, here — anything that features some sort of saturation or distortion will reduce the dynamic range, and when gain’s applied that will bring up the noise along with everything else.

A common cause of unwanted noise is analogue-modelling plug-ins, which are often too authentic! This UAD Studer model, for example, features a noise control which, by default, is hidden beneath a panel. Several Waves plug-ins also have noise switched on by default, and in some mixes compression and limiting further down the signal chain can raise this to annoying levels.A common cause of unwanted noise is analogue-modelling plug-ins, which are often too authentic! This UAD Studer model, for example, features a noise control which, by default, is hidden beneath a panel. Several Waves plug-ins also have noise switched on by default, and in some mixes compression and limiting further down the signal chain can raise this to annoying levels.Then it’s time to consider how to tackle the remaining noise. If noise is prominent while the wanted signal is playing, consider using a dedicated noise-removal tool like iZotope RX, Waves X-Noise and so on. These can be highly effective, but they’ll sometimes leave unwanted artifacts. If the noise only bothers you between sections of wanted sound, then level automation on the individual sources is an obvious solution — if the noise isn’t there, it can’t be amplified by any plug-in.

Gates do this automatically, of course, but they just don’t sound right to me unless they have a variable ‘floor’ control, or whatever you prefer to call it (the bundled one in Cubase, for example, doesn’t have this feature), as the abrupt cutting off of the noise just serves to draw attention to the fact it was there in the first place. I’d rather have noise right the way through than hear that! But even then, level automation is a more precise option.

A more natural-sounding technique than a gate is to automate the frequency of a low-pass filter so that the filter rolls down the spectrum in sections between the wanted bits of sound. The sound remains, but it is less noticeable, and the transition between sections is less glaring too. This is how the old Symetrix noise gates worked, and where sophisticated noise-removal tools such as iZotope RX aren’t called for, or aren’t working for you for whatever reason, it’s a useful technique to try on hissy guitar sounds; I’ll bet it will work for you too.

I haven’t yet found a plug-in that does this automatically for you, but you can do this in Cockos Reaper using its dynamic automation system (it’s called Parameter Modulation; see http://sosm.ag/reaper-parametermod for details). This can be set up to make the filter frequency move dynamically in relation to the amplitude of the source signal — so as the vocal phrase finishes, the filter rolls off the more noticeable high-frequency hiss. It takes a bit of finessing to get it right, but if you’re already using Reaper, it could be just the ticket!

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Wednesday, February 25, 2015

Tuesday, February 24, 2015

Q Are mineral-wool acoustic panels safe?

Sound Advice : Recording

I’m looking to get some acoustic panels of the rigid fibreglass/Rockwool type for my bedroom studio. I’ve read a few things online about possible dangers — in particular about respiratory issues (though I think carcinogenic impact was proven negative). Now, I know you wouldn’t use them if you thought there were a danger, but there’s a lot of guff online about potential issues. As my daughter has slight respiratory issues already, I definitely don’t want to make things worse. Can you offer me any advice on this?

SOS Forum post

We often advocate the use of mineral wool for use in DIY acoustic treatment — it’s safe to use provided you take sensible precautions.We often advocate the use of mineral wool for use in DIY acoustic treatment — it’s safe to use provided you take sensible precautions.SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: They’re not inherently carcinogenic, as far as I am aware, but loose fibres can certainly cause irritation. For that reason, mineral wool should always be covered with a breathable but tightly woven fabric that will prevent the release of fibres. If you’re making DIY panels, then spraying the mineral-wool slabs with a diluted PVA glue helps to keep fibre shedding down, and make sure you wear a mask while handling the stuff.

Commercial mineral-wool-based panels can smell unpleasant at first, due to the glues used, so I always unwrap them and leave in the garage for a week or so, to let the fishy glue smell dissipate before installation!

Monday, February 23, 2015

Saturday, February 21, 2015

Q Do surround-sound speakers need to be of the same type?

Sound Advice : Mixing

I’m a sound engineer planning to have a surround-sound setup. The problem is, I already have a pair of Yamaha MSP5s and I don’t really want to spend the money required to have three more of them for surround use! So, can I have Yamaha HS5s for the centre and rear speakers, and also a different sub (something like KRK 10S)? Will it really make such a difference?

SOS Forum post

SOS Reviews Editor Matt Houghton replies: Well, depending on what sort of surround material you’re mixing on it could be workable — but it will never be ideal, and if you’re serious about doing commercial surround work in the longer term you’re going to want speakers designed to be used together. In the meantime, the trick in this sort of setup is to do all of your critical EQ/balance work in mono or stereo in the first place on your best pair of speakers, and then to pan things out to do your surround mix — safe in the knowledge that your EQ and relative levels already work, and that you’ll have more space for separation when mixing in surround. Your speakers might not match perfectly, but you’ll already have done most of the tonal work, and you’re just trying to get the right idea of positioning. A few years ago when I interviewed Kevin Paul (who, as then Head Engineer at Mute, had just re-mixed the entire Depeche Mode back catalogue for surround sound), I asked about budget setups for home-studio owners who wanted to dip their toes in the world of surround-sound. For similar reasons to those I gave above, he suggested that you could probably get by for a while with a home-cinema surround setup as a secondary monitoring system, with your critical work being done on your usual higher-quality stereo pair.

Cheap home-cinema surround systems like this might help you get a feel for surround-sound mixing, but they’re far from the best tool for the job.Cheap home-cinema surround systems like this might help you get a feel for surround-sound mixing, but they’re far from the best tool for the job.SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns adds: Plenty of professional surround monitoring systems use different, typically smaller, speakers in the rear channels. However, the critical aspect is that they are voiced to sound the same as the front speakers, so that the tonality remains consistent regardless of where any sound is panned. Most high-end monitor manufacturers pay a great deal of attention to this aspect, specifically so that their monitors can be mixed and matched in the way you describe. However, tonal consistency is likely to be less well maintained at the budget end of the market, so it’s something you’ll need to assess first hand.

As Matt has said, the work-around is to make all your critical EQ and balance judgements on the higher-quality front L/R speakers first, and only after you have the stereo track working well to think about re-panning things for surround. You will probably then notice distracting tonality changes as sounds move onto the other speakers, but you’ll have to restrain yourself from reaching for the EQ controls, as you’ll otherwise be equalising for the speakers rather than the content! You may well need to tweak the relative balance of things after panning to compensate for the inherent panning-law effects, but be careful to tweak only because of panning offsets, not because a speaker’s response is over or under-emphasising the signal.

I’d add a small word of caution about using a domestic home-theatre system. Yes, the five mains speakers will all be identical and will have the same tonality, which is helpful. However, they’ll be compact and most of the bass will be diverted to the subwoofer via in-built bass-management arrangements. The potential problem is that home-theatre subwoofers are generally designed with the emphasis on delivering impressive explosions, not tuneful bass. Most seem to have a one-note bass quality so, once again, make all your bass EQ and balance decisions on your good-quality stereo speakers, not the home theatre system!

I’m a sound engineer planning to have a surround-sound setup. The problem is, I already have a pair of Yamaha MSP5s and I don’t really want to spend the money required to have three more of them for surround use! So, can I have Yamaha HS5s for the centre and rear speakers, and also a different sub (something like KRK 10S)? Will it really make such a difference?

SOS Forum post

SOS Reviews Editor Matt Houghton replies: Well, depending on what sort of surround material you’re mixing on it could be workable — but it will never be ideal, and if you’re serious about doing commercial surround work in the longer term you’re going to want speakers designed to be used together. In the meantime, the trick in this sort of setup is to do all of your critical EQ/balance work in mono or stereo in the first place on your best pair of speakers, and then to pan things out to do your surround mix — safe in the knowledge that your EQ and relative levels already work, and that you’ll have more space for separation when mixing in surround. Your speakers might not match perfectly, but you’ll already have done most of the tonal work, and you’re just trying to get the right idea of positioning. A few years ago when I interviewed Kevin Paul (who, as then Head Engineer at Mute, had just re-mixed the entire Depeche Mode back catalogue for surround sound), I asked about budget setups for home-studio owners who wanted to dip their toes in the world of surround-sound. For similar reasons to those I gave above, he suggested that you could probably get by for a while with a home-cinema surround setup as a secondary monitoring system, with your critical work being done on your usual higher-quality stereo pair.

Cheap home-cinema surround systems like this might help you get a feel for surround-sound mixing, but they’re far from the best tool for the job.Cheap home-cinema surround systems like this might help you get a feel for surround-sound mixing, but they’re far from the best tool for the job.SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns adds: Plenty of professional surround monitoring systems use different, typically smaller, speakers in the rear channels. However, the critical aspect is that they are voiced to sound the same as the front speakers, so that the tonality remains consistent regardless of where any sound is panned. Most high-end monitor manufacturers pay a great deal of attention to this aspect, specifically so that their monitors can be mixed and matched in the way you describe. However, tonal consistency is likely to be less well maintained at the budget end of the market, so it’s something you’ll need to assess first hand.

As Matt has said, the work-around is to make all your critical EQ and balance judgements on the higher-quality front L/R speakers first, and only after you have the stereo track working well to think about re-panning things for surround. You will probably then notice distracting tonality changes as sounds move onto the other speakers, but you’ll have to restrain yourself from reaching for the EQ controls, as you’ll otherwise be equalising for the speakers rather than the content! You may well need to tweak the relative balance of things after panning to compensate for the inherent panning-law effects, but be careful to tweak only because of panning offsets, not because a speaker’s response is over or under-emphasising the signal.

I’d add a small word of caution about using a domestic home-theatre system. Yes, the five mains speakers will all be identical and will have the same tonality, which is helpful. However, they’ll be compact and most of the bass will be diverted to the subwoofer via in-built bass-management arrangements. The potential problem is that home-theatre subwoofers are generally designed with the emphasis on delivering impressive explosions, not tuneful bass. Most seem to have a one-note bass quality so, once again, make all your bass EQ and balance decisions on your good-quality stereo speakers, not the home theatre system!

Friday, February 20, 2015

Thursday, February 19, 2015

Q How long should I spend on a mix?

Sound Advice : Mixing

Mike Senior

I’ve found your Mix Rescue articles really useful, but I was struck by how much detail Mike Senior goes into. I get why he does it, but I don’t have a feel for how long it takes. If I’m mixing like this, should I be spending hours, days, weeks, or what?

Dave Jackson, via email

SOS contributor Mike Senior replies: I get asked this question frequently, but it’s difficult to answer in the abstract because the time required varies tremendously between projects. Sometimes I’ve spent more than two weeks mixing one song, but at other times I’ve finished three or four mixes in one day. Mix Rescue projects typically take between three and five days.

SOS’s Mix Rescue features often go into huge amounts of detail, but a good proportion of the time and effort involved is often spent correcting issues that could have been more quickly corrected when writing or tracking. A pure mixing job should not take you more than a couple of days — and can often be completed much more quickly. SOS’s Mix Rescue features often go into huge amounts of detail, but a good proportion of the time and effort involved is often spent correcting issues that could have been more quickly corrected when writing or tracking. A pure mixing job should not take you more than a couple of days — and can often be completed much more quickly. Why the wide variation? My job is to turn the supplied multitracks into a finished product, and as the production values of ‘finished–sounding’ vary enormously depending on the style of music and its projected market, the amount of time required to reach that quality threshold inevitably varies too. In terms of pure mixing activities (processing, effects and fader moves), a sensibly recorded small acoustic session might need little more than simple balancing and panning to give a nicely representative organic sound, and therefore require only a few hours per song to complete. Large–scale chart–targeted productions, on the other hand, might require two or three days to make sense of a blizzard of different programmed and overdubbed sonic elements, while keeping the overall sonics within extremely tight mass–market stylistic tolerances in terms of mix tonality, short-/long–term dynamics, and vocal/hook intelligibility.

The reason most Mix Rescue projects take longer is that they almost always involve more than just mixing work. For example, I usually end up spending a day or so editing, simply because most Mix Rescuees haven’t realised how carefully the leading releases in their target style manage timing and tuning issues. In many cases, the recordings demanded to implement a given style simply aren’t there either. I might get DI’d acoustic guitars where the genre calls for miked–up sounds, say, or there may be no appropriate double tracks/layers, or the electric guitars may be too distorted, or the drums may have had ancient worn–out heads... The list is endless, even before you add a truly inventive catalogue of inadvisable recording methods into the equation! Every one of these tracking–stage misjudgments costs the mix engineer time, either in trying to salvage something useful from what’s provided, or in working around crucial omissions.

The time requirements really balloon where the project needs more creative production input. On a sonic level, if no–one has really committed to decisions about what the record should sound like during tracking, that leaves the mix engineer having to take a (more or less educated) guess, and that frequently involves a good deal of trial and error. The same applies if the arrangement or structure of the music aren’t serving the music well. Or if the artist is concerned that there simply isn’t enough melodic/harmonic interest in the parts as recorded, such that additional MIDI parts, recorded overdubs, or editing/mixing stunts become necessary to increase the amount of ear–candy.Hopefully that gives you some idea how long my Mix Rescue projects take. But, as I said, much of this time is spent on things other than actual mixing. In my view, a mix that takes me more than two days in any style raises serious questions about the recording and production techniques used prior to mixdown. While there are clearly many things that can be ‘fixed in the mix’, that’s an extraordinarily inefficient way of working if you have any alternative! I can’t tell you how often I’ve wished, while doing the Mix Rescue column, that I could travel back in time and ask the reader to spend just 10 more minutes doing something while tracking that would have saved me hours (quite literally) of remedial work. To quote Trevor Horn, “the mix is the worst time to do anything”!

Mike Senior

I’ve found your Mix Rescue articles really useful, but I was struck by how much detail Mike Senior goes into. I get why he does it, but I don’t have a feel for how long it takes. If I’m mixing like this, should I be spending hours, days, weeks, or what?

Dave Jackson, via email

SOS contributor Mike Senior replies: I get asked this question frequently, but it’s difficult to answer in the abstract because the time required varies tremendously between projects. Sometimes I’ve spent more than two weeks mixing one song, but at other times I’ve finished three or four mixes in one day. Mix Rescue projects typically take between three and five days.

SOS’s Mix Rescue features often go into huge amounts of detail, but a good proportion of the time and effort involved is often spent correcting issues that could have been more quickly corrected when writing or tracking. A pure mixing job should not take you more than a couple of days — and can often be completed much more quickly. SOS’s Mix Rescue features often go into huge amounts of detail, but a good proportion of the time and effort involved is often spent correcting issues that could have been more quickly corrected when writing or tracking. A pure mixing job should not take you more than a couple of days — and can often be completed much more quickly. Why the wide variation? My job is to turn the supplied multitracks into a finished product, and as the production values of ‘finished–sounding’ vary enormously depending on the style of music and its projected market, the amount of time required to reach that quality threshold inevitably varies too. In terms of pure mixing activities (processing, effects and fader moves), a sensibly recorded small acoustic session might need little more than simple balancing and panning to give a nicely representative organic sound, and therefore require only a few hours per song to complete. Large–scale chart–targeted productions, on the other hand, might require two or three days to make sense of a blizzard of different programmed and overdubbed sonic elements, while keeping the overall sonics within extremely tight mass–market stylistic tolerances in terms of mix tonality, short-/long–term dynamics, and vocal/hook intelligibility.

The reason most Mix Rescue projects take longer is that they almost always involve more than just mixing work. For example, I usually end up spending a day or so editing, simply because most Mix Rescuees haven’t realised how carefully the leading releases in their target style manage timing and tuning issues. In many cases, the recordings demanded to implement a given style simply aren’t there either. I might get DI’d acoustic guitars where the genre calls for miked–up sounds, say, or there may be no appropriate double tracks/layers, or the electric guitars may be too distorted, or the drums may have had ancient worn–out heads... The list is endless, even before you add a truly inventive catalogue of inadvisable recording methods into the equation! Every one of these tracking–stage misjudgments costs the mix engineer time, either in trying to salvage something useful from what’s provided, or in working around crucial omissions.

The time requirements really balloon where the project needs more creative production input. On a sonic level, if no–one has really committed to decisions about what the record should sound like during tracking, that leaves the mix engineer having to take a (more or less educated) guess, and that frequently involves a good deal of trial and error. The same applies if the arrangement or structure of the music aren’t serving the music well. Or if the artist is concerned that there simply isn’t enough melodic/harmonic interest in the parts as recorded, such that additional MIDI parts, recorded overdubs, or editing/mixing stunts become necessary to increase the amount of ear–candy.Hopefully that gives you some idea how long my Mix Rescue projects take. But, as I said, much of this time is spent on things other than actual mixing. In my view, a mix that takes me more than two days in any style raises serious questions about the recording and production techniques used prior to mixdown. While there are clearly many things that can be ‘fixed in the mix’, that’s an extraordinarily inefficient way of working if you have any alternative! I can’t tell you how often I’ve wished, while doing the Mix Rescue column, that I could travel back in time and ask the reader to spend just 10 more minutes doing something while tracking that would have saved me hours (quite literally) of remedial work. To quote Trevor Horn, “the mix is the worst time to do anything”!

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Q. How can I automate the level of vocals against a backing track?

Sound Advice : Mixing

I'm currently involved in composing music tracks for a self-help medical audio program and I would like to be able to create tracks that combine subliminal messages with music. Subliminal messages work best when hardly heard — just a very little bit — so I'm looking for some automatic way of keeping the vocal signal just audible as the music rises and falls in level. I read your article about automatic ducking techniques in Cubase, and was hoping to use this information to achieve my goal, but I still haven't been able to achieve what I'm after, namely to get the vocal level to follow the music level. I read the instructions several times, and played around with the settings, but it still doesn't work. Can you advise?Via SOS web site

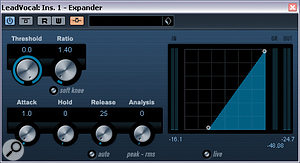

SOS contributor Mike Senior replies: The Cubase Notes article (SOS May 2009: /sos/may09/articles/cubasetech_0509.htm) you're referring to won't directly help you to achieve what you want, because it gives instructions on how to reduce the level of one signal (the electric guitars in the article's example) in response to another signal's level increase (the lead vocal in the article's example). A better alternative would be to follow the instructions in my June 2010 Cubase column (/sos/jun10/articles/cubase_0610.htm), where I describe how to simulate the effects of Waves Vocal Rider using a side-chain-enabled Expander plug-in. In Mike Senior's June 2010 Cubase column, we showed how to simulate the effects of Waves' Vocal Rider using a side-chain-enabled Expander plug-in; we can see part of the process here. This technique automates the vocal to correspond with the level of the backing track: particularly useful for our reader, who is creating tracks that incorporate subliminal messages.In Mike Senior's June 2010 Cubase column, we showed how to simulate the effects of Waves' Vocal Rider using a side-chain-enabled Expander plug-in; we can see part of the process here. This technique automates the vocal to correspond with the level of the backing track: particularly useful for our reader, who is creating tracks that incorporate subliminal messages.Q. How can I automate the level of vocals against a backing track?

The down side of that approach, though, is that expanders with external side-chain access aren't particularly common, so here's an alternative scheme that uses a triggered compressor instead (these are more common):

Create a parallel channel fed from the vocal. (You could also just duplicate the vocal track, but this is a little less elegant because it makes later processing of the overall vocal tone less convenient.)

Compress the parallel channel.

Invert its polarity.

Now trigger its gain-reduction from the music channel. (If you have several music channels, then perhaps send them first to a group bus, so you can easily feed the compressor side-chain from there.)

Assuming that your plug-in delay compensation is working, this setup should give you the automatic level riding you're after. When the mix is quiet the parallel channel is less compressed, and will cancel the lead vocal more (reducing its level), whereas, when the mix is loud the parallel channel will be more compressed and will cancel the lead vocal less (increasing its level).

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Friday, February 13, 2015

Q What’s the difference between PPM and VU meters?

I recently came across a plug-in that incorporates both VU and PPM metering, and it got me thinking: what exactly is the difference between the two?

Via SOS web site

SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: These are both, strictly speaking, obsolete analogue metering formats! In short, the VU meter shows an averaged signal level and gives an impression of perceived loudness, while a PPM indicates something closer to the peak amplitude of the input signal. However, in our modern digital world, neither meter really performs adequately, and the current state of the art is enshrined in the new ITU-R BS1770 standard, which is being adopted very rapidly around the world in the broadcast sector and elsewhere. This is an excellent metering system that provides a new and very accurate Loudness Meter scaled in LUFS — which does a much better job than the VU — along with an oversampled True Peak Meter scaled in dBTP, which does a much better job than the PPM. I urge everyone to use these meters in preference to everything else!

However, for historians, the VU or Volume Unit meter was conceived in 1939 and originally called the SVI or Standard Volume Indicator. It was developed as a collaborative project by CBS, NBC and Bell Labs in America and, since the meter scale was calibrated in 'volume units', that's the name that stuck! The SVI/VU meter is amongst the simplest of all audio meter designs and essentially behaves as a simple averaging voltmeter, with a moderate attack (or 'integration') time of about 300ms. The needle fall-back time is roughly the same, and the full meter specification is enshrined in the IEC 60268-17 (1990) standard.

A VU meter's display is influenced by both the amplitude and duration of the applied signal. With a steady sine-wave signal applied to the input, a VU meter gives an accurate reading of the RMS (root-mean-square, or average) signal voltage. However, with more complex musical or speech signals the meter will typically under-read, and a sustained sound will produce a significantly higher indication than a brief transient signal, even if both have the same peak voltage. In theory, a VU meter should respond to both the positive and negative halves of the input audio signal, but the cheapest implementations sometimes only measure one half of the waveform, and so can provide different readings with asymmetrical signals compared to full VU meters.

The simplicity of the VU meter design makes it relatively cheap to implement, and so VU meters tend to be employed in equipment that requires a lot of meters — such as multitrack recorders or mixers — or where accurate level indication is not essential.

The reference level indication is 0VU, but the audio level required to achieve that could be whatever the user wished. The original SVI implementation included an adjustable attenuator to accommodate any standard operating level up to +24dBu (US broadcasters still use nominal reference levels of +8dBu). Modern VU meters usually omit the user-adjustable attenuator and are typically set to give a 0VU indication for an input level of either 0dBu or +4dBu. The latter is the most common 'pro standard', but a lot of manufacturers use the former alignment, including Mackie. In general, then, the SVI or VU meter tends to show the average signal voltage, and gives a reasonable indication of perceived loudness.

The Peak Programme Meter or PPM is a much more elaborate design and pre-dates the VU, as its development started in 1932, with the meter we know today appearing in 1938. Despite the name, PPMs don't actually indicate the true peak of the signal voltage. Early units employed a 10ms integration time (Type II meters), while later units reduced the integration time to 4ms (Type I meters). These short integration times were selected specifically to ignore the fastest transient peaks, and as a result the PPM is often referred to as a 'quasi-peak' meter to differentiate it from true-peak meters. Typically, very brief transient signals will be under-read by about 4dB. The reason for ignoring brief transients was to encourage operators to set slightly higher levels than would otherwise be the case, on the assumption that any transient overloads in recording or transmitting equipment would be inaudible, which is generally the case for analogue overloads of less than 1ms. Q What’s the difference between PPM and VU meters?

Whereas the VU meter has fairly equal attack and release times, the PPM is characterised by having a very slow fall-back time, taking over 1.5 seconds to fall back 20dB (the specifications vary slightly for Type I and II meters). The reasoning for the slow fall-back was to reduce eye-fatigue and make the peak indication easier to assimilate. The specifications of all types of PPM are detailed in IEC 60268-10 (1991), and the scale used by the BBC comprises the numbers 1-7 in white on a black background. There are 4dB between each mark, and PPM 4 is the reference level (0dBu). EBU, DIN and Nordic variants of the PPM exist with different scales. The EBU version replaces the BBC numbers with the equivalent dBu values, while both the Nordic and DIN versions accommodate a much wider dynamic range.

Via SOS web site

SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: These are both, strictly speaking, obsolete analogue metering formats! In short, the VU meter shows an averaged signal level and gives an impression of perceived loudness, while a PPM indicates something closer to the peak amplitude of the input signal. However, in our modern digital world, neither meter really performs adequately, and the current state of the art is enshrined in the new ITU-R BS1770 standard, which is being adopted very rapidly around the world in the broadcast sector and elsewhere. This is an excellent metering system that provides a new and very accurate Loudness Meter scaled in LUFS — which does a much better job than the VU — along with an oversampled True Peak Meter scaled in dBTP, which does a much better job than the PPM. I urge everyone to use these meters in preference to everything else!

However, for historians, the VU or Volume Unit meter was conceived in 1939 and originally called the SVI or Standard Volume Indicator. It was developed as a collaborative project by CBS, NBC and Bell Labs in America and, since the meter scale was calibrated in 'volume units', that's the name that stuck! The SVI/VU meter is amongst the simplest of all audio meter designs and essentially behaves as a simple averaging voltmeter, with a moderate attack (or 'integration') time of about 300ms. The needle fall-back time is roughly the same, and the full meter specification is enshrined in the IEC 60268-17 (1990) standard.

A VU meter's display is influenced by both the amplitude and duration of the applied signal. With a steady sine-wave signal applied to the input, a VU meter gives an accurate reading of the RMS (root-mean-square, or average) signal voltage. However, with more complex musical or speech signals the meter will typically under-read, and a sustained sound will produce a significantly higher indication than a brief transient signal, even if both have the same peak voltage. In theory, a VU meter should respond to both the positive and negative halves of the input audio signal, but the cheapest implementations sometimes only measure one half of the waveform, and so can provide different readings with asymmetrical signals compared to full VU meters.

The simplicity of the VU meter design makes it relatively cheap to implement, and so VU meters tend to be employed in equipment that requires a lot of meters — such as multitrack recorders or mixers — or where accurate level indication is not essential.

The reference level indication is 0VU, but the audio level required to achieve that could be whatever the user wished. The original SVI implementation included an adjustable attenuator to accommodate any standard operating level up to +24dBu (US broadcasters still use nominal reference levels of +8dBu). Modern VU meters usually omit the user-adjustable attenuator and are typically set to give a 0VU indication for an input level of either 0dBu or +4dBu. The latter is the most common 'pro standard', but a lot of manufacturers use the former alignment, including Mackie. In general, then, the SVI or VU meter tends to show the average signal voltage, and gives a reasonable indication of perceived loudness.

The Peak Programme Meter or PPM is a much more elaborate design and pre-dates the VU, as its development started in 1932, with the meter we know today appearing in 1938. Despite the name, PPMs don't actually indicate the true peak of the signal voltage. Early units employed a 10ms integration time (Type II meters), while later units reduced the integration time to 4ms (Type I meters). These short integration times were selected specifically to ignore the fastest transient peaks, and as a result the PPM is often referred to as a 'quasi-peak' meter to differentiate it from true-peak meters. Typically, very brief transient signals will be under-read by about 4dB. The reason for ignoring brief transients was to encourage operators to set slightly higher levels than would otherwise be the case, on the assumption that any transient overloads in recording or transmitting equipment would be inaudible, which is generally the case for analogue overloads of less than 1ms. Q What’s the difference between PPM and VU meters?

Whereas the VU meter has fairly equal attack and release times, the PPM is characterised by having a very slow fall-back time, taking over 1.5 seconds to fall back 20dB (the specifications vary slightly for Type I and II meters). The reasoning for the slow fall-back was to reduce eye-fatigue and make the peak indication easier to assimilate. The specifications of all types of PPM are detailed in IEC 60268-10 (1991), and the scale used by the BBC comprises the numbers 1-7 in white on a black background. There are 4dB between each mark, and PPM 4 is the reference level (0dBu). EBU, DIN and Nordic variants of the PPM exist with different scales. The EBU version replaces the BBC numbers with the equivalent dBu values, while both the Nordic and DIN versions accommodate a much wider dynamic range.

Thursday, February 12, 2015

Wednesday, February 11, 2015

Q Is it a good idea to use a subwoofer in my home studio?

Sound Advice : Mixing

Matt Houghton

I have all the acoustic treatment I can fit into my home studio already, and have a decent amp and good–quality (PMC) passive monitors, but I have trouble judging low frequencies — so I’m thinking of adding a subwoofer. What should I consider when selecting one, and is it a good idea in my situation?

Bill Gambles, via email

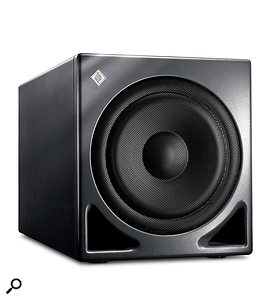

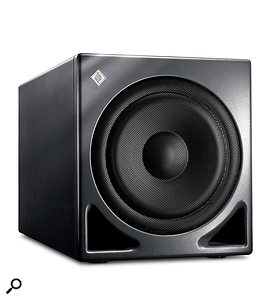

SOS Reviews Editor Matt Houghton replies: You don’t state what model of speaker you have, but PMC claim that their TB2 model, for example, offers a ‘useful’ frequency response down as low as 40Hz. I can think of very few music–making scenarios where you should need particularly accurate monitoring lower than that — and in those few cases you’d need a room that could cope. If your room can’t cope, and you really do need to judge the level of a 30–50Hz sine wave, then it’s a pretty trivial matter to check on a modern frequency analyser plug–in what’s going on.

Subwoofers aren’t necessarily the right answer to your bass–monitoring woes, particularly in studios that are set up in domestic spaces — no matter how high the quality of subwoofer.Subwoofers aren’t necessarily the right answer to your bass–monitoring woes, particularly in studios that are set up in domestic spaces — no matter how high the quality of subwoofer.With this in mind, I’d suggest that you start not by thinking about subwoofers, but by attempting to check what level of bass your speakers are actually putting out into your room: play some bass–rich material over them and stand in a corner of the room, where the bass build–up is likely to be greatest, and walk around the room boundary. If you can hear an increase in very low frequencies, then lack of bass from your speakers isn’t your main problem — and adding a sub will probably just prove to be an expensive way to make matters worse.

If your speakers are doing their job, you need to do something about the room. You say you’ve already installed as much acoustic treatment as you can, but perhaps you can reconsider the nature of the acoustic treatment you’ve installed. To achieve remotely accurate low–frequency monitoring in a domestic space the room must be treated with ample bass trapping. The idea is to absorb low-frequency waves so that they don’t bounce around the room causing all those nasty peaks and nulls. It’s pretty much impossible to install too much bass trapping, but often impossible to install enough! We’ve covered this subject many times over the years, but for ideas on relatively compact bass traps check out our Studio SOS feature from July 2006 (http://sosm.ag/studiosos-0706).

Of course, you may live in a rather grander residence than the one I pictured from your description, and perhaps have a large room or double garage at your disposal, with plenty of room for adequate bass trapping. In this case a sub might be worth considering — but even then, only once you’ve made efforts to treat the room properly. If you decide that you really do need a sub, then there’s a whole host of questions you need to answer, not just which model is best. Thankfully, our Technical Editor wrote an in–depth article on this very subject back in April 2007 (http://sosm.ag/all-about-subwoofers). I’d suggest reading that before you reach for your credit card!

Matt Houghton

I have all the acoustic treatment I can fit into my home studio already, and have a decent amp and good–quality (PMC) passive monitors, but I have trouble judging low frequencies — so I’m thinking of adding a subwoofer. What should I consider when selecting one, and is it a good idea in my situation?

Bill Gambles, via email

SOS Reviews Editor Matt Houghton replies: You don’t state what model of speaker you have, but PMC claim that their TB2 model, for example, offers a ‘useful’ frequency response down as low as 40Hz. I can think of very few music–making scenarios where you should need particularly accurate monitoring lower than that — and in those few cases you’d need a room that could cope. If your room can’t cope, and you really do need to judge the level of a 30–50Hz sine wave, then it’s a pretty trivial matter to check on a modern frequency analyser plug–in what’s going on.

Subwoofers aren’t necessarily the right answer to your bass–monitoring woes, particularly in studios that are set up in domestic spaces — no matter how high the quality of subwoofer.Subwoofers aren’t necessarily the right answer to your bass–monitoring woes, particularly in studios that are set up in domestic spaces — no matter how high the quality of subwoofer.With this in mind, I’d suggest that you start not by thinking about subwoofers, but by attempting to check what level of bass your speakers are actually putting out into your room: play some bass–rich material over them and stand in a corner of the room, where the bass build–up is likely to be greatest, and walk around the room boundary. If you can hear an increase in very low frequencies, then lack of bass from your speakers isn’t your main problem — and adding a sub will probably just prove to be an expensive way to make matters worse.

If your speakers are doing their job, you need to do something about the room. You say you’ve already installed as much acoustic treatment as you can, but perhaps you can reconsider the nature of the acoustic treatment you’ve installed. To achieve remotely accurate low–frequency monitoring in a domestic space the room must be treated with ample bass trapping. The idea is to absorb low-frequency waves so that they don’t bounce around the room causing all those nasty peaks and nulls. It’s pretty much impossible to install too much bass trapping, but often impossible to install enough! We’ve covered this subject many times over the years, but for ideas on relatively compact bass traps check out our Studio SOS feature from July 2006 (http://sosm.ag/studiosos-0706).

Of course, you may live in a rather grander residence than the one I pictured from your description, and perhaps have a large room or double garage at your disposal, with plenty of room for adequate bass trapping. In this case a sub might be worth considering — but even then, only once you’ve made efforts to treat the room properly. If you decide that you really do need a sub, then there’s a whole host of questions you need to answer, not just which model is best. Thankfully, our Technical Editor wrote an in–depth article on this very subject back in April 2007 (http://sosm.ag/all-about-subwoofers). I’d suggest reading that before you reach for your credit card!

Q. How can I create a 'fake' M/S setup that is mono compatible?

I thought I had the whole M/S thing down until I listened to a commercial record and realised their stereo image was wider than mine and yet still perfectly mono compatible!In order to convert a mono source to an M/S pair, I bus the source audio to two separate tracks. On one track, the audio is unchanged and routed to the stereo bus centre (which I label 'Mid'). The other I delay by around 10ms, then split it to the left and right stereo bus, with the right side inverted (I label this track 'Side'). The 'Side' track cancels when I sum to mono.The problem I'm having is that the stereo image is not very wide. While it is clearly in stereo, it does not reach the extremes of the stereo field as it would by utilising the Haas effect. When I use a simple Haas trick, I achieve the width I desire (ie. a hole in the middle), but it is not acceptably mono compatible. Is there a trick I am missing to achieve the width that I desire in my pseudo-M/S setup, yet also maintain mono compatibility?

Via SOS web site

SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: When you use this method of creating a fake stereo signal from a mono source, the apparent width is determined entirely by the amount of Side signal relative to the amount of Mid signal. No Side means mono. Loads of Side means wide perceived stereo image. Too much Side signal means a hole in the middle and quiet mono!

So you should be able to make the track as wide as you want — even to the level of a hole in the middle — just by further pushing the level of the Side signal. Changing delay time also affects perceived width and size. Larger delays (30-70 ms) create more hall-like effects, while shorter delays (5-30 ms) are more subtle and less 'roomy'.

However, this kind of M/S-based fake stereo is never as convincing as real stereo. You inherently end up with a mush of frequencies spread across the sound stage; your original mono source is spread across the image like butter on bread. There is no discrete spatial positioning, and no coherent imaging. Basically, it isn't real stereo, it never can be real stereo, and comparison with a real stereo recording is pretty pointless and always disappointing!

Moreover, created in the way you describe, the stereo image will tend to be bass-heavy on the left-hand side, because the relatively short delay you are using will tend to allow low frequencies to sum in phase on the left and out of phase on the right. This can be cured by inserting a high-pass filter before (or after) the delay line to remove bass from the Side signal. Set it to about 100-150 Hz to ensure the bass content stays central.Top: The arrangement our reader is currently using to produce a wider stereo image, which results in reduced bass on the right-hand side. The fake stereo image arises because some frequencies are stronger in one side than the other, due to the offset comb-filtering resulting from combining the original and delayed signals with the same and opposite polarities. More 'fake Side' ('S') level results in a wider perceived image. In the lower diagram, the fake 'S' signal has been high-pass filtered, avoiding bass cancellation in the right-hand side.Top: The arrangement our reader is currently using to produce a wider stereo image, which results in reduced bass on the right-hand side. The fake stereo image arises because some frequencies are stronger in one side than the other, due to the offset comb-filtering resulting from combining the original and delayed signals with the same and opposite polarities. More 'fake Side' ('S') level results in a wider perceived image. In the lower diagram, the fake 'S' signal has been high-pass filtered, avoiding bass cancellation in the right-hand side.

The Haas effect — which you can employ by panning the original source to one side and a short-delayed version of it to the other — can sound very wide indeed, but usually isn't very mono compatible. The only way to make a single source fill a stereo sound-stage in any kind of convincing way — in my humble opinion — is to record it in stereo in a decent-sounding acoustic space, or use a really good reverb processor to achieve a similar thing. There are other techniques that can be used to create pseudo-stereo effects using dedicated stereo-width enhancers and variations on the distortion and chorusing theme, but they all tend to change the tonality to some extent, which may not be what you're after.

Via SOS web site

SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: When you use this method of creating a fake stereo signal from a mono source, the apparent width is determined entirely by the amount of Side signal relative to the amount of Mid signal. No Side means mono. Loads of Side means wide perceived stereo image. Too much Side signal means a hole in the middle and quiet mono!

So you should be able to make the track as wide as you want — even to the level of a hole in the middle — just by further pushing the level of the Side signal. Changing delay time also affects perceived width and size. Larger delays (30-70 ms) create more hall-like effects, while shorter delays (5-30 ms) are more subtle and less 'roomy'.

However, this kind of M/S-based fake stereo is never as convincing as real stereo. You inherently end up with a mush of frequencies spread across the sound stage; your original mono source is spread across the image like butter on bread. There is no discrete spatial positioning, and no coherent imaging. Basically, it isn't real stereo, it never can be real stereo, and comparison with a real stereo recording is pretty pointless and always disappointing!

Moreover, created in the way you describe, the stereo image will tend to be bass-heavy on the left-hand side, because the relatively short delay you are using will tend to allow low frequencies to sum in phase on the left and out of phase on the right. This can be cured by inserting a high-pass filter before (or after) the delay line to remove bass from the Side signal. Set it to about 100-150 Hz to ensure the bass content stays central.Top: The arrangement our reader is currently using to produce a wider stereo image, which results in reduced bass on the right-hand side. The fake stereo image arises because some frequencies are stronger in one side than the other, due to the offset comb-filtering resulting from combining the original and delayed signals with the same and opposite polarities. More 'fake Side' ('S') level results in a wider perceived image. In the lower diagram, the fake 'S' signal has been high-pass filtered, avoiding bass cancellation in the right-hand side.Top: The arrangement our reader is currently using to produce a wider stereo image, which results in reduced bass on the right-hand side. The fake stereo image arises because some frequencies are stronger in one side than the other, due to the offset comb-filtering resulting from combining the original and delayed signals with the same and opposite polarities. More 'fake Side' ('S') level results in a wider perceived image. In the lower diagram, the fake 'S' signal has been high-pass filtered, avoiding bass cancellation in the right-hand side.

The Haas effect — which you can employ by panning the original source to one side and a short-delayed version of it to the other — can sound very wide indeed, but usually isn't very mono compatible. The only way to make a single source fill a stereo sound-stage in any kind of convincing way — in my humble opinion — is to record it in stereo in a decent-sounding acoustic space, or use a really good reverb processor to achieve a similar thing. There are other techniques that can be used to create pseudo-stereo effects using dedicated stereo-width enhancers and variations on the distortion and chorusing theme, but they all tend to change the tonality to some extent, which may not be what you're after.

Tuesday, February 10, 2015

Q. Could I use Cubase System Link to slave my VST plug-ins?

I'm looking to set up another computer alongside my main computer to slave all my CPU-draining VST instruments and effects. I'm currently using Cubase 5, but looking to upgrade to 6 soon, and would like to utilise the VST System Link option. After doing some Internet research, I know System Link will only work with certain audio interfaces. I have a budget of around $500 to buy the two interfaces, and I'm wondering what you could advise me to get for that? It would be great if you could give me some information on setting up and using System Link, as there is very little on the Internet to help!

George Morton via email

SOS Reviews Editor Matt Houghton replies: Personally, I wouldn't recommend using System Link, as there are alternatives around that allow you to link two machines without requiring a second audio interface.

The one I have most experience with is FX Teleport, by FX-Max (www.fx-max.com/fxt). There's a free demo that you can try using any type of network connection, including USB and Firewire, but if you decide to use it you'll get better results from a faster network connection, such as Gigabit Ethernet. The one additional piece of hardware I'd recommend investing in is a KVM box, which allows you to use a screen, mouse and keyboard with multiple computers. That's pretty much essential when working in this way. I'd thoroughly recommend FX Teleport if another computer is the answer to your problems.

Before you invest, though, do make sure that it is more CPU power that you need. Availability of memory, or hard-drive loading, could also be a cause of problems. It could be that, for example, results are limited by your hard-disk performance, particularly if you are running an operating system, audio files and streaming sample instruments all from the same disk, in which case running those three things from separate drives might help.

Memory is often not a huge problem area, although it can be an issue on some 32-bit systems, particularly where you have a lot of hardware installed. First, there's a maximum of 4GB available in Windows XP 32-bit, of which only 2 or 3 GB is available to each application — and all of the plug-ins running within Cubase count as one programme! On my old XP system, I had 4GB of memory installed, but had only 2.3GB available to applications, due to the way in which Windows allocated memory address space to my various DSP cards.

In 64-bit versions of Windows, this limitation is removed. You might run into problems with older 32-bit plug-ins if you try to run the 64-bit version of Cubase, but in my current system I'm running 32-bit Cubase on Windows 7 64-bit, with the JBridge utility allowing me to run 64-bit plug-ins (such as Kontakt) in their own address space.

If you haven't tried it yet, I'd also suggest experimenting with Cubase's Freeze facility, which allows you to 'freeze' audio and instrument tracks. This essentially performs a temporary render of those tracks and unloads any plug-ins to free up precious computer resources. You can unfreeze at any time if you need to go back and tweak, and even when frozen you still have access to features such as level and pan automation.

Finally, another option is to consider upgrading to a modern multi-core PC. That might not be quite within your budget, but if you've not upgraded for a few years, you'll be amazed at how much more you can do in a single system. One advantage is that you'll only have the noise of one machine to put up with, because remember that the more computers you have running, the greater the sound of whirring fans will be in your studio!

George Morton via email

SOS Reviews Editor Matt Houghton replies: Personally, I wouldn't recommend using System Link, as there are alternatives around that allow you to link two machines without requiring a second audio interface.

The one I have most experience with is FX Teleport, by FX-Max (www.fx-max.com/fxt). There's a free demo that you can try using any type of network connection, including USB and Firewire, but if you decide to use it you'll get better results from a faster network connection, such as Gigabit Ethernet. The one additional piece of hardware I'd recommend investing in is a KVM box, which allows you to use a screen, mouse and keyboard with multiple computers. That's pretty much essential when working in this way. I'd thoroughly recommend FX Teleport if another computer is the answer to your problems.

Before you invest, though, do make sure that it is more CPU power that you need. Availability of memory, or hard-drive loading, could also be a cause of problems. It could be that, for example, results are limited by your hard-disk performance, particularly if you are running an operating system, audio files and streaming sample instruments all from the same disk, in which case running those three things from separate drives might help.

Memory is often not a huge problem area, although it can be an issue on some 32-bit systems, particularly where you have a lot of hardware installed. First, there's a maximum of 4GB available in Windows XP 32-bit, of which only 2 or 3 GB is available to each application — and all of the plug-ins running within Cubase count as one programme! On my old XP system, I had 4GB of memory installed, but had only 2.3GB available to applications, due to the way in which Windows allocated memory address space to my various DSP cards.

In 64-bit versions of Windows, this limitation is removed. You might run into problems with older 32-bit plug-ins if you try to run the 64-bit version of Cubase, but in my current system I'm running 32-bit Cubase on Windows 7 64-bit, with the JBridge utility allowing me to run 64-bit plug-ins (such as Kontakt) in their own address space.

If you haven't tried it yet, I'd also suggest experimenting with Cubase's Freeze facility, which allows you to 'freeze' audio and instrument tracks. This essentially performs a temporary render of those tracks and unloads any plug-ins to free up precious computer resources. You can unfreeze at any time if you need to go back and tweak, and even when frozen you still have access to features such as level and pan automation.

Finally, another option is to consider upgrading to a modern multi-core PC. That might not be quite within your budget, but if you've not upgraded for a few years, you'll be amazed at how much more you can do in a single system. One advantage is that you'll only have the noise of one machine to put up with, because remember that the more computers you have running, the greater the sound of whirring fans will be in your studio!

Monday, February 9, 2015

Q Is it a problem using commercial tracks as a reference if audio files are clipped?

Sound Advice : Recording

Hugh Robjohns

I’ve put together a group of commercial reference mixes. I chose them because I liked the way they sounded, but I noticed that two of them had been clipped. Are these mixes still worth using as references? And how can they clip without distorting in an ugly fashion? Finally, why would the engineer do that, especially with folk music?

Via SOS forum

Is a file really clipping? The only way to tell is by using a true–peak meter, such as this one in Steinberg’s Cubase.Is a file really clipping? The only way to tell is by using a true–peak meter, such as this one in Steinberg’s Cubase.SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: First, let me highlight a small but critically important difference: hitting 0dBFS is not synonymous with ‘clipping’ — it’s a perfectly legitimate situation to have a sample reaching 0dBFS, and a signal is only ‘clipped’ if a sample should have been allocated a higher quantisation value than was available. The only way to check the real situation is to use a ‘True Peak’ meter, as specified in the BS.1770 loudness metering recommendations — there are plenty of those from various plug–in developers. Other forms of ‘clip meter’ in your DAW may illuminate before the onset of clipping, or when there’s one or more samples at 0dBFS, and some may be user–calibrated — you need to be sure what your meter is actually telling you before you pay too much attention to the flashing red lights!

Is a file really clipping? The only way to tell is by using a true–peak meter, such as this one in Steinberg’s Cubase.Is a file really clipping? The only way to tell is by using a true–peak meter, such as this one in Steinberg’s Cubase.SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: First, let me highlight a small but critically important difference: hitting 0dBFS is not synonymous with ‘clipping’ — it’s a perfectly legitimate situation to have a sample reaching 0dBFS, and a signal is only ‘clipped’ if a sample should have been allocated a higher quantisation value than was available. The only way to check the real situation is to use a ‘True Peak’ meter, as specified in the BS.1770 loudness metering recommendations — there are plenty of those from various plug–in developers. Other forms of ‘clip meter’ in your DAW may illuminate before the onset of clipping, or when there’s one or more samples at 0dBFS, and some may be user–calibrated — you need to be sure what your meter is actually telling you before you pay too much attention to the flashing red lights!

The fact that the material doesn’t sound clipped or distorted would suggest that it is, in fact, reaching 0dBFS by design (through a normalisation process or very precise limiter), but not actually being clipped. However, it’s also worth noting that while it’s possible to hear just a single sample clipping, with some material you won’t hear it even if it lasts more than 16 samples. It’s partly frequency dependent, but also dependent on the reconstructed waveform, which ordinary peak sample meters make no attempt to analyse (hence the need for a true-peak meter).

Are ‘peak–level’ mixes useful as references? Yes, of course they are: it’s the sound character of the mix that you’re referencing, so if the mix sounds good to you that’s all that matters. Note, though, that playing things back at the same loudness is essential if you’re to make meaningful comparisons.

There are, unfortunately, plenty of mixes that are genuinely clipped, which therefore distort to some degree. “Why would ‘they’ do that?” is a question I’ve been asking for decades! It’s technically unnecessary and ultimately destructive, but ‘art’ is often illogical, and pressure from the misguided ‘loudness wars’ lobby has encouraged or forced people to do daft things for decades, sadly.

Hugh Robjohns

I’ve put together a group of commercial reference mixes. I chose them because I liked the way they sounded, but I noticed that two of them had been clipped. Are these mixes still worth using as references? And how can they clip without distorting in an ugly fashion? Finally, why would the engineer do that, especially with folk music?

Via SOS forum

Is a file really clipping? The only way to tell is by using a true–peak meter, such as this one in Steinberg’s Cubase.Is a file really clipping? The only way to tell is by using a true–peak meter, such as this one in Steinberg’s Cubase.SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: First, let me highlight a small but critically important difference: hitting 0dBFS is not synonymous with ‘clipping’ — it’s a perfectly legitimate situation to have a sample reaching 0dBFS, and a signal is only ‘clipped’ if a sample should have been allocated a higher quantisation value than was available. The only way to check the real situation is to use a ‘True Peak’ meter, as specified in the BS.1770 loudness metering recommendations — there are plenty of those from various plug–in developers. Other forms of ‘clip meter’ in your DAW may illuminate before the onset of clipping, or when there’s one or more samples at 0dBFS, and some may be user–calibrated — you need to be sure what your meter is actually telling you before you pay too much attention to the flashing red lights!

Is a file really clipping? The only way to tell is by using a true–peak meter, such as this one in Steinberg’s Cubase.Is a file really clipping? The only way to tell is by using a true–peak meter, such as this one in Steinberg’s Cubase.SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: First, let me highlight a small but critically important difference: hitting 0dBFS is not synonymous with ‘clipping’ — it’s a perfectly legitimate situation to have a sample reaching 0dBFS, and a signal is only ‘clipped’ if a sample should have been allocated a higher quantisation value than was available. The only way to check the real situation is to use a ‘True Peak’ meter, as specified in the BS.1770 loudness metering recommendations — there are plenty of those from various plug–in developers. Other forms of ‘clip meter’ in your DAW may illuminate before the onset of clipping, or when there’s one or more samples at 0dBFS, and some may be user–calibrated — you need to be sure what your meter is actually telling you before you pay too much attention to the flashing red lights!The fact that the material doesn’t sound clipped or distorted would suggest that it is, in fact, reaching 0dBFS by design (through a normalisation process or very precise limiter), but not actually being clipped. However, it’s also worth noting that while it’s possible to hear just a single sample clipping, with some material you won’t hear it even if it lasts more than 16 samples. It’s partly frequency dependent, but also dependent on the reconstructed waveform, which ordinary peak sample meters make no attempt to analyse (hence the need for a true-peak meter).

Are ‘peak–level’ mixes useful as references? Yes, of course they are: it’s the sound character of the mix that you’re referencing, so if the mix sounds good to you that’s all that matters. Note, though, that playing things back at the same loudness is essential if you’re to make meaningful comparisons.

There are, unfortunately, plenty of mixes that are genuinely clipped, which therefore distort to some degree. “Why would ‘they’ do that?” is a question I’ve been asking for decades! It’s technically unnecessary and ultimately destructive, but ‘art’ is often illogical, and pressure from the misguided ‘loudness wars’ lobby has encouraged or forced people to do daft things for decades, sadly.

Q. Can you help me with MP3 file conversion?

Can you explain a few things about creating MP3s? I'm currently converting WAVs to 24-bit, 44.1kHz and then converting them to MP3, but I'm not entirely sure what effect this kind of conversion has on the sound. Will my method have a higher-quality outcome than 16-bit WAVs converted to MP3?Via SOS web site

SOS contributor Martin Walker replies: I doubt that you'll hear any difference in practice by increasing the bit depth from 16 to 24. As long as you leave a few dB of headroom to give your MP3 encoder some 'space' to perform a clean result, the main decision to be made with MP3s is the target bit-rate. MP3 files can be created at CBR (Constant Bit Rate) values from 8Kbps to 320Kbps. Spoken word is still perfectly intelligible down to about 24Kbps, which is usually perfectly sufficient for podcasts, talk radio, and so on. Solo acoustic music performances could be acceptable at 48Kbps, although 64Kbps is probably more in line with AM radio quality.

For reasonable-quality ensemble music, many people consider 128Kbps a good baseline, especially if the intended destination is computer speakers or in-car audio systems. However, when listening on a hi-fi or on studio playback gear, many musicians find 128Kbps difficult to listen to, especially since the frequency response falls off rapidly above 16kHz, high‑frequency sounds such as cymbals sound distinctly harsh, and you can often hear a low-level background 'warbling' sound, which is the main reason that some people dislike this rate.

If you're looking for the best compromise for your MP3 files between compression ratio and audio quality, bit-rates of 160Kbps or 192Kbps are generally recommended, with 192Kbps, in particular — often being classed as 'near CD' quality — suitable for complex music or tracks with lots of bass content. Only on expensive playback systems can most people tell the difference between 192Kbps and CD quality.

Further up the scale, if you want some compression but minimal degradation in sound, 256Kbps is a good compromise compared with CD audio, since the frequency response is generally identical to the original up to about 18kHz, and the difference between the two is barely discernible by most people, even on high-end systems. For ultimate MP3 quality, you could choose 320Kbps, but so few people can hear the difference between this and 256Kbps (or real CDs, for that matter) that it's generally a waste of disk space.

Of course, the main point of all these conversions is to reduce file size, and most MP3 encoders also offer a choice of VBR (Variable Bit Rate), in which the bit rate is altered dynamically during your track. Because VBR can rise during complex passages and drop during simpler sections, with some material it can sound significantly better when compared to a similarly sized CBR file, and instead of numeric values you may be offered a quality setting anywhere from 'highest' to 'lowest'. However, VBR is rarely used for online audio streaming because its constantly changing data stream encourages glitches and errors, as it does on some older MP3 players, particularly when fast forward or rewind controls are used.

The above guidelines are fine for the average punter, but as musicians, what should we really be listening for when deciding on bit-rate? Well, because of the way MP3 encoding relies on one frequency 'masking' another nearby at a lower level, any instrument that glides from one frequency to another (such as fretless or acoustic bass, guitar whammy-bar excursions, Theremin or trombone solos) may result in audible artifacts, so listen out for these and use a higher setting if required.MP3 encoding reduces file size partly by Frequency Masking (discarding information that is unlikely to be heard because of nearby louder tones), but it can be fooled by some types of music, such as gliding or pure tones.MP3 encoding reduces file size partly by Frequency Masking (discarding information that is unlikely to be heard because of nearby louder tones), but it can be fooled by some types of music, such as gliding or pure tones.

Another killer combination for the MP3 encoder is a pure solo tone, such as a long, high vocal or flute note, or guitar feedback tone, with complex but quiet instrumentation behind it. Listen out for distortion or general fuzziness where the encoder has decided that parts of the background instrumentation are redundant: they might be with a rock band and screaming guitar solo, but not with a quartet featuring a flute solo.

Ultimately, though, all these choices pale into insignificance if your MP3 files are intended for online streaming. Many sites, such as Soundcloud, YouTube, and so on, convert incoming audio to their own chosen format so, unless you're offering downloadable MP3 files, you're often stuck with whatever quality choices these other delivery sites choose for you (typically around 128Kbps).

Published in SOS January 2012

SOS contributor Martin Walker replies: I doubt that you'll hear any difference in practice by increasing the bit depth from 16 to 24. As long as you leave a few dB of headroom to give your MP3 encoder some 'space' to perform a clean result, the main decision to be made with MP3s is the target bit-rate. MP3 files can be created at CBR (Constant Bit Rate) values from 8Kbps to 320Kbps. Spoken word is still perfectly intelligible down to about 24Kbps, which is usually perfectly sufficient for podcasts, talk radio, and so on. Solo acoustic music performances could be acceptable at 48Kbps, although 64Kbps is probably more in line with AM radio quality.

For reasonable-quality ensemble music, many people consider 128Kbps a good baseline, especially if the intended destination is computer speakers or in-car audio systems. However, when listening on a hi-fi or on studio playback gear, many musicians find 128Kbps difficult to listen to, especially since the frequency response falls off rapidly above 16kHz, high‑frequency sounds such as cymbals sound distinctly harsh, and you can often hear a low-level background 'warbling' sound, which is the main reason that some people dislike this rate.

If you're looking for the best compromise for your MP3 files between compression ratio and audio quality, bit-rates of 160Kbps or 192Kbps are generally recommended, with 192Kbps, in particular — often being classed as 'near CD' quality — suitable for complex music or tracks with lots of bass content. Only on expensive playback systems can most people tell the difference between 192Kbps and CD quality.

Further up the scale, if you want some compression but minimal degradation in sound, 256Kbps is a good compromise compared with CD audio, since the frequency response is generally identical to the original up to about 18kHz, and the difference between the two is barely discernible by most people, even on high-end systems. For ultimate MP3 quality, you could choose 320Kbps, but so few people can hear the difference between this and 256Kbps (or real CDs, for that matter) that it's generally a waste of disk space.

Of course, the main point of all these conversions is to reduce file size, and most MP3 encoders also offer a choice of VBR (Variable Bit Rate), in which the bit rate is altered dynamically during your track. Because VBR can rise during complex passages and drop during simpler sections, with some material it can sound significantly better when compared to a similarly sized CBR file, and instead of numeric values you may be offered a quality setting anywhere from 'highest' to 'lowest'. However, VBR is rarely used for online audio streaming because its constantly changing data stream encourages glitches and errors, as it does on some older MP3 players, particularly when fast forward or rewind controls are used.