Whether archiving projects, creating stems or saving CPU resources, Cubase 8’s Render In Place feature has you covered.

Whether you need to save some CPU resources in a complex project, create a set of stems for mixing and/or mastering, or simply ensure that you can either move your project to another audio environment or preserve it for archive purposes, the Render In Place facility that was added in both the Pro and Artist versions of Cubase 8 can be a really useful tool.

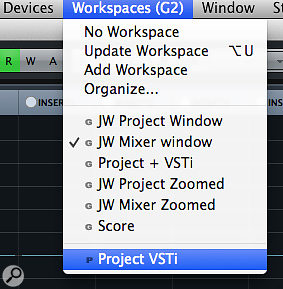

The Render In Place settings give you plenty of flexibility when rendering your audio or MIDI events and tracks.

The Render In Place settings give you plenty of flexibility when rendering your audio or MIDI events and tracks.

Rendered Superfluous?

As the name suggests, Render In Place (RIP) provides a way of turning existing audio or virtual-instrument tracks into new audio files. RIP is not without its limitations, as we’ll see, but it is both versatile and powerful. Cubase already has a number of other tools that provide audio-rendering services, of course, including Bounce Selection, Track Freeze and Export Audio Mixdown. So does RIP render (sorry!) these existing functions superfluous? Well, yes and no, because while there’s certainly plenty of overlap between these features, and Steinberg may see RIP as an eventual replacement for some or even all of the above facilities, my educated guess is that all those older features will hang around for some time so that users with established workflows are not unduly disturbed. I’m sure that I will continue to use Export Audio Mixdown for final stereo mixdown tasks, for example, and perhaps for archiving projects, but for other tasks I can see myself turning to RIP.

Super Saver

A strength of RIP is that it can be applied at different ‘levels’, such as to single or multiple events on a track, or to a single track, or multiple tracks at once, or even to a whole project. Selecting a track means the render process will apply to all events on the track. Selecting individual clips means the render will be limited to them.

With the target material selected, go to Edit/Render In Place. You’ll be invited to choose Render (with Current Settings) or Render Settings. The latter option, which you’ll want to choose for first-time use, opens a dialogue box in which you can configure exactly how the render process will be executed. The settings you specify are retained until you revisit the dialogue and make further changes. Although small, this dialogue box holds a wide range of possibilities but, for now, let’s focus on its upper portion, where you have to make just two choices.

First, from the uppermost drop-down menu, you can choose between As Separate Events (a new rendered audio event is created to match each clip on the source track), As Block Events (source events that are touching are rendered as a single new event), or As One Event (a single audio event is rendered, spanning all the selected events in the source track).

The second choice is a ‘one of four’ affair and where things get a little more interesting, as you can control exactly what is rendered to the new audio track/event. For example, Dry (Transfer Channel Setting) renders the pre-insert audio signal to a new audio event on a new channel, with any channel settings from the source track (insert plug-ins, channel-strip settings, EQ) being copied to the new track. In the case of rendering a virtual instrument or rendering some VariAudio tweaks on a vocal track, this is really useful — it gives you the exact sound of the original track but still allows full control of it’s standard processing elements when mixing.

![]() Your rendered audio is placed on a new audio track immediately beneath the source track.The other three options gradually include more of the source track/event’s settings into the render. Channel Settings renders all the inserts, channel strip and EQ settings, Complete Signal Path includes any send effects too, whereas Complete Signal Path + Master FX adds in any processing placed on the master stereo output bus to the rendered audio. There are occasions when either of these options would be useful and/or appropriate. For example, you might use the Complete Signal Path option if you wanted to lock in all your standard track and send-level Cubase processing before moving your whole project over to another dedicated mixing/mastering application. You need to be careful with this if you have any dynamics processing on the bus, though — because the whole mix isn’t triggering your bus compressor, the results may sound a little ‘off’.

Your rendered audio is placed on a new audio track immediately beneath the source track.The other three options gradually include more of the source track/event’s settings into the render. Channel Settings renders all the inserts, channel strip and EQ settings, Complete Signal Path includes any send effects too, whereas Complete Signal Path + Master FX adds in any processing placed on the master stereo output bus to the rendered audio. There are occasions when either of these options would be useful and/or appropriate. For example, you might use the Complete Signal Path option if you wanted to lock in all your standard track and send-level Cubase processing before moving your whole project over to another dedicated mixing/mastering application. You need to be careful with this if you have any dynamics processing on the bus, though — because the whole mix isn’t triggering your bus compressor, the results may sound a little ‘off’.

If you use either ‘Complete Channel’ options, the Tail Size setting in the bottom half of the dialogue box may need tweaking. This allows you to specify the length of an additional audio ‘tail’ to each rendered audio event, which enables you to include the decay of any reverb or delay processing in the render.

By default, when you apply RIP at the level of a single track, a new audio track is created immediately beneath the source track (an upper case ‘(R)’ is added to the track name to indicate it is a rendered version) and the source track is muted. However, if you’re rendering to save CPU resources (for example, a complex VSTi track), selecting the Disable Source Tracks option via the drop-down menu at the bottom releases the CPU and RAM resources used by the source track. This is, in effect, Track Freezing, but with greater flexibility in terms of exactly what is being rendered — it’s potentially very useful indeed.

Stem Creator

If you select multiple tracks, or events on multiple tracks, you have more options. For example, provided you don’t have Dry (Transfer Channel Settings) selected, you should see a Mix Down To One Track option. Left unticked, each track is rendered as described above. The benefit of that is speed — you need only initiate the process once. If you tick the Mix Down To One Track box all selected tracks/events are rendered to a single audio track, which is a great way to simplify a complex project. For example, if you have a lead vocal or bass guitar part that’s spread over multiple tracks, you can easily consolidate it down to a single track, making it easier to manage as part of a final mix.

Render In Place’s Mix Down To One Track option is a useful way to create stems, as shown here for a set of guitar tracks.Another potential application for this option is the creation of stem tracks for your major instrument groups (drums, bass, rhythm guitars, keys, and so on). That could be useful in music-to-picture work or working with a mastering engineer, or even just for you to simplify the mixing process. Used in this context, RIP mirrors some of the features offered by the Channel Batch Export (CBE) option in the Export Audio Mixdown window. Unlike with CBE, you have to execute RIP individually for each stem you wish to create, but you get much more detailed control about what you wish to include in each stem.

Render In Place’s Mix Down To One Track option is a useful way to create stems, as shown here for a set of guitar tracks.Another potential application for this option is the creation of stem tracks for your major instrument groups (drums, bass, rhythm guitars, keys, and so on). That could be useful in music-to-picture work or working with a mastering engineer, or even just for you to simplify the mixing process. Used in this context, RIP mirrors some of the features offered by the Channel Batch Export (CBE) option in the Export Audio Mixdown window. Unlike with CBE, you have to execute RIP individually for each stem you wish to create, but you get much more detailed control about what you wish to include in each stem.

Live Long & Prosper

If you’ve been working with audio for any length of time, you’ll be only too aware of how quickly recording formats can become tomorrow’s museum pieces. Production ‘in the box’ can be particularly vulnerable to changes in virtual instrument or audio plug-in availability, unless you are very careful about your project archive process.

Because RIP allows you to process multiple tracks in a single pass, you can easily create multiple archive versions that (a) are essentially ‘audio-only’ versions and could, in principle, be opened in any DAW at some point in the future regardless of what plug-in technologies are available, and (b) contain different amounts of the track-level processing rendered within the audio.

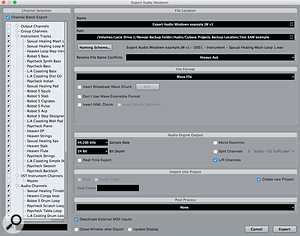

The Render In Place settings shown here would create an audio-only version of your project — ideal for archival or if running low on computer resources when mixing.For example, if you select all the tracks in your project, and apply the RIP settings shown in the final screenshot, the end result is an audio-only version of your project where each rendered track embeds all the original channel-level plug-ins, EQ or strip settings, but not any send or master-bus effects. You do practice safe sequencing don’t you? RIP means you have no excuse for shocking accidents. With Remove Source Tracks selected, the newly rendered version of your project will also have low CPU/RAM resource demands and be ready to mix again at some point in the future, regardless of what plug-ins your system might then have available.

The Render In Place settings shown here would create an audio-only version of your project — ideal for archival or if running low on computer resources when mixing.For example, if you select all the tracks in your project, and apply the RIP settings shown in the final screenshot, the end result is an audio-only version of your project where each rendered track embeds all the original channel-level plug-ins, EQ or strip settings, but not any send or master-bus effects. You do practice safe sequencing don’t you? RIP means you have no excuse for shocking accidents. With Remove Source Tracks selected, the newly rendered version of your project will also have low CPU/RAM resource demands and be ready to mix again at some point in the future, regardless of what plug-ins your system might then have available.

Workaround

Good though the first iteration of RIP was — it was introduced with Cubase v8 — there were a few catches. Steinberg tackled the most obviously problematic of these (that RIP automatically rendered mono channels as stereo audio files) in the v8.0.20 update. Render In Place can now handle both mono and stereo source material and the format is retained in the rendered version. As vocals are generally recorded in mono, this was an important practical ‘fix’ and this kind of fine-tuning is very welcome.

At the time of writing, some other challenges remain, though. For example, RIP can’t currently handle plug-ins whose side-chain input is in use. Some users have also reported problems when working with VST instruments where multiple MIDI tracks feed the same instrument but multiple output channels are used. Let’s hope Steinberg attend to issues like this sooner or later, but in the meantime you can always use the Export Audio Mixdown feature for any such problematic rendering tasks.

Published October 2015