Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions. Where there are no limits! Enjoy your visit!

Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions

| Company Founded | 2005 |

|---|

| Overview | Our services include Sound Engineering, Audio Post-Production, System Upgrades and Equipment Consulting. |

|---|---|

| Mission | Our mission is to provide excellent quality and service to our customers. We do customized service. |

Tuesday, June 30, 2015

Saturday, June 27, 2015

Friday, June 26, 2015

Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: Humberto Gatica

Inside Track: Michael Bublé ‘You’re Nobody Till Somebody Loves You’

People + Opinion : Artists / Engineers / Producers / ProgrammersIn a rare interview, legendary engineer and producer Humberto Gatica explains how he and singer Michael Bublé breathed new life into big‑band swing music — with stunning results.

Paul Tingen

Humberto Gatica at the Euphonix desk in his own studio in Los Angeles.Humberto Gatica at the Euphonix desk in his own studio in Los Angeles.Photo: Mr Bonzai

Still only 34, singer Michael Bublé has almost single‑handedly made swing and big‑band music fashionable again, with well over 20 million album sales to date. The Canadian broke through to the mainstream in 2003 with an eponymously titled album, and followed it with It's Time (2005), the Grammy‑winning Call Me Irresponsible (2007) and Crazy Love (2009). The latter reached number one in the US, the UK, Canada, Australia and many other countries. In addition, Bublé won a second Grammy this year in the category Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album, with the live Bublé Meets Madison Square Garden.

As the old saying goes, behind every great singer there's a great production team, and Bublé's team is spearheaded by two living legends of the American music industry. Canadian David Foster and Chilean Humberto Gatica were both instrumental in helping the singer update swing and big‑band music for the 21st Century. Foster is the 15‑time Grammy‑winning writer of megahits such as 'Love Theme from St Elmo's Fire', Chicago's 'Hard To Say I'm Sorry' and Celine Dion's 'The Power Of The Dream', and has also produced the likes of Dion, Whitney Houston and Barbra Streisand. Foster discovered Bublé in 2000, signed him to his label, 143 Records, and produced large parts of the four above‑mentioned albums.

Meanwhile, Humberto Gatica's 35‑year career has seen him work with almost every big‑name American artist, from Michael Jackson to Barbra Streisand, Madonna to Mariah Carey, in the process collecting no fewer than 16 Grammy awards. Gatica worked as a producer, engineer and mixer on all of Bublé's albums.

Three producers worked on Crazy Love. Foster produced half of the 14 songs, Bob Rock five, and Gatica two: the big‑band track 'You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You' and the barbershop‑inspired vocal swing of 'Stardust'. Gatica engineered the tracks he produced, and together with Jochem van der Saag (interviewed in SOS April 2009) he engineered all the Foster‑produced tracks. Gatica also mixed all of the tracks, apart from the first single, 'Haven't Met You Yet', which fell to Chris Lord‑Alge. In this article, we'll be looking in detail at Gatica's work on 'You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You'.

Crazy Stuff

Gatica's small rack of vital outboard equipment. At the top is the custom‑made Eduardo Fayed preamp he uses on Michael Bublé's vocals; beneath that are Lang and GML equalisers, Neve 33609 stereo compressor, AMS RMX16 reverb and two humble Yamaha SPX990 multi‑effects units.Gatica's small rack of vital outboard equipment. At the top is the custom‑made Eduardo Fayed preamp he uses on Michael Bublé's vocals; beneath that are Lang and GML equalisers, Neve 33609 stereo compressor, AMS RMX16 reverb and two humble Yamaha SPX990 multi‑effects units.

At the time of the interview, Humberto Gatica is juggling several projects, amongst them an album of orchestral arrangements of Diane Warren songs and work with Quincy Jones on the 'We Are The World 2010' benefit single for Haiti. In between all this, from his brand‑new studio in Los Angeles, Gatica elaborates on his work on Michael Bublé's Crazy Love, and on how both this album and his work in general aim to combine the best of the old and the new.

"I'm so busy that I keep my studio working all the time, and I'm happy with that,” explains Gatica, his Chilean accent and syntax still very much apparent. "I have a Euphonix desk here, with Pro Tools. I like the Euphonix sound, because it has a little bit of the analogue touch to it. The EQ is very musical, and in fact I recorded the first three Bublé studio albums, the first three Josh Groban albums, a couple of Celine albums, and a bunch of other stuff on a Euphonix desk. The Madison Square Garden live album was done on a Neve, because my studio wasn't ready yet, and Crazy Love was recorded and mixed on Neve consoles as well.

"As far as outboard is concerned, I'm still attached to the analogue world, even though I'm slowly discovering the possibilities presented by plug‑ins. I little by little learn to use them and I program what they can do in my head, so I know what to go for when necessary. But I'm much more in tune with analogue gear; I immediately know what I want and where to find it, whether it's EQ, compression, or reverbs. But you have to use today's technology. You can't just close your eyes and bury your head and say that you're only going to do it one way. So I chose what's available now to my advantage, and with the experience that I bring from the other side of the coin, I have finally learned to have a perfect balance. I don't have to think about it any more, it just happens naturally. The way I use microphones, EQ, compression, the way I go into Pro Tools, I've been able to program my brain to today's technology so I'm able to get what I want.

"You can do so much crazy stuff now in Pro Tools, move things around, change, shift, chop, tune, that you couldn't do in analogue. It makes me happy to use it. Pro Tools is a fantastic device if used properly and if you don't get carried away — though some people work with such average musicians that they have no choice but to work with Pro Tools and to fix and compress the heck out of things. I also think that digital now sounds pretty close to the way that analogue used to sound. I still think, though, that there is a certain spread, depth, and weight and musicality with analogue that's not reproduced today. There are some great‑sounding new records, but in the past we made better‑sounding records, with more soul. The higher sample rates help, so I've tried using 96k, but it's a pain. It uses too much space and slows down the session, and I like to move fast. So I'm now back to 24/48. I still think that the converters of the old Sony 3348 [digital multitrack tape machine] are incredible. When I worked on Michael's albums at David Foster's studio, we always went through a 3348. For my current studio I bought an old 3348, and I process my signal through its converters.

"I still lay everything out on the desk. To me, with the kind of music that I'm doing, the box [computer] is a danger. As soon as you go into the box, things have a tendency to get sterile and predictable. The box is a one‑dimensional device designed for a different kind of music. For some music it's ideal, but it destroys the musicality, the emotions, the orchestrations and the chords in the music that I do. It takes away energy and spirit. I don't care how much analogue you rent in, it's not the real thing. Michael also didn't want that approach. It's OK to record into the box, but then you have to bring the elements back out again into a whirl of feelings in analogue, and into the way you can feel the moves with a desk. For me, it's impossible to get the sound I want with just a mouse and plug‑ins. No way. It's like trying to make an incredible meal with boxing gloves on and all the food is in cans or is frozen. I can't do it.”

Purity Of Sound

The Pro Tools Session for 'You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You'.The Pro Tools Session for 'You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You'.

The synthesis of the old and the new, analogue and digital, the desk and Pro Tools, lies at the heart of everything Gatica does these days. It extends into the actual music‑making and arranging arena, as is illustrated by his work with Michael Bublé. "With the Bublé albums, we were able to perfectly balance the traditional and the contemporary. We were using synth sounds and loops and so on, while being cautious about how we introduced them in the mix. Sometimes they were explicit and exposed, sometimes they worked more in the background and added to the overall feel, where you can't tell exactly what's happening, but you can feel that there's something different. If we had not added these elements, we'd have made a very traditional album, à la Frank Sinatra. With all the artists we work with, we try to create their own sound, even if it is traditional music. On Michael's first album there's a track called 'Fever', and you can hear a lot of loops kicking in and giving a nice spin to the vibe of the song. There's a bit of an edge. The same in the song 'Hold On' [the forthcoming second single from Crazy Love] which has a bit of roughness in the electric guitars. Michael also writes singles that are completely outside of the swing world. He is the only artist who is able to step out of character and come back into it again like that.”

Crazy Love embodies this combination of the old and the new in many different ways. It contains old‑fashioned songs, amongst them early 20th Century classics such as 'Georgia On My Mind', 'Stardust', and 'All Of Me', mid‑century songs such as 'You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You', 'Cry Me A River' and the soul classic 'Some Kind of Wonderful', and rock songs including the Eagles' 1980 hit 'Heartache Tonight', Van Morrison's 1970 classic 'Crazy Love' and Ron Sexsmith's 2004 song 'Whatever It Takes'. There are also two songs written by Bublé with Alan Chang and Amy S Foster. The album contains a wide variety of ingredients, among them in‑the‑background Cubase programming by Jochem van der Saag, distorted electric guitars, in‑your‑face drum kits, big bands, horn and string sections and barbershop singing. The most immediately apparent contemporary characteristic of the album, however, is its sound, which is rich, bright, detailed, transparent: in‑your‑face, but not overly so.

"The vocals are the most important aspect of the entire recording for me,” insists Gatica. "I pay a lot of attention to vocal recording, and I have found the zone where the vocals behave best. With Celine it's the Telefunken 251, into one of my customised mic pres, Neve 33609 [compressor] and GML EQ. I use the 251 with almost everybody, it's my favourite microphone, but with Michael I use a vintage tube Neumann U47. My mic pres were made 25 years ago by Eduardo Fayed, a Brazilian genius. I used them for the recording of the first 'We Are The World'. It challenges every other mic pre on the planet in terms of purity and clean sound. Dave Foster had two, but somehow they died, and so my two mic pres are the only ones left in the world. Fayed's mic pres work wonderfully on Celine. She's one of the most challenging vocalists on the planet to record, because of her incredible range and the way she can sing very softly, and then suddenly she'll shift her sound to a very powerful mid‑range. If the mic and the mic pre don't respond properly, you'll get a mid‑rangey sound that she won't like. She's the most sensitive, wonderful, amazing vocalist I've ever worked with, and she'll immediately hear in her earphones if her vocals sound compressed or whatever.”

'You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You'

Written by James Cananaugh, Russ Morgan, Larry Stock

Produced by Humberto GaticaSecrets Of The Mix Engineers: Humberto Gatica

Humberto Gatica: "In the case of this song, I was producing, arranging, engineering and mixing, so before explaining the technical details to you, I have to stress that the technical aspect is something that I have done for so many years that it has become second nature. My primary concern when I'm producing is arrangement and performance. After the sound, which in part inspires the production, is set, I let go and completely disconnect myself from that aspect. After that, all I think about is the creative aspect, the feel, the arrangement, what the arrangement is doing to the melody, how it is affecting the vocal performance, and so on. I'm like an ice hockey player who doesn't think about skating any more, but only about the game and scoring goals. In the case of this song, my input in the arrangement was a collaboration. The arrangements were already kind of there, because Michael and his band had already performed the song live. We just upgraded the arrangement for the recorded version. We beefed it up with outside ideas from Alan [Chang] and me.

"We recorded this track at the Warehouse [in Vancouver] with Michael's live band. It was one of the first times that the band was participating on one of his albums. We were very excited about that. Playing live is one thing, but playing in a studio is much more demanding, and so we had to tighten things up and make sure they were more accurate. Everything was recorded live, there were no overdubs, apart from some fixes on Michael's vocal because there were some pops in the live take. I like the artists to sing the song with the arrangement, so I can better judge what I'm looking for. Michael always wants to do a live vocal to capture the feel. He sings in an iso booth, and the quality of his live singing is as good as that of his overdubs. I also had the drums, piano, double bass and guitars in iso rooms, and the rest of the band set up in a kind of horse-shoe arrangement, with trombones to the left, saxophones to the right, and trumpets towards the centre. I later kept that positioning in the mix. I recorded the strings at the same time, but later I overdubbed them again to have more control over the sound. The room sounded fantastic, very bright, with a nice resonance in the horns, and so I used lots of ambient mics, which allowed me to get some real live energy into the recording.

"In terms of microphones, I had a Sennheiser MD421 and [Neumann] FET 47 on the bass drum, AKG C452 and Shure SM57 on the snare, 57s on the toms, AKG 452 on the hi‑hat, [Neumann] TLM170 for the overheads, [Neumann] M50 for the ambience. The upright bass was recorded with two FET 47s on each 'f' hole and a [Neumann] KM84 close to the neck. The bass player did not have a pickup this time. The piano was recorded with an AKG C414 and a [Neumann] M49, and for the guitar I had an SM57 on the amp and also an AKG 452 right by the guitarist's hand, so I could pick up a little bit of the strumming sound.

"For anything brass I love Neumann, so trombones and trumpets were recorded with U87s, and the saxophone with 47 FETs. I used the Neumann 67 and 87s on all the strings apart from the cellos, for which I used the AKG 452. I like to have options of close, section, and ambient microphones. The room at the Warehouse has an interesting height, and I put the M50 up at the balcony, and also put up two [Telefunken ELAM] 251s as ambient mics, just to fool around and check the frequency response up there. In terms of the signal chains, I took my Eduardo Fayed mic pres with me to Vancouver and used them on Michael's vocals, as well as the trumpets, to make sure they sounded a little fatter. Other than that, I used the mic pres of the Warehouse's Neve 'AIR' desk [one of three originally designed to George Martin and Geoff Emerick's specifications for AIR Studios], which is a good‑sounding console. I compressed the bass, the guitars and the piano a bit, just to have a bit more control, but the brass, never; the brass has to breathe.

"Michael wanted from the beginning to have a record that sounded real, that sounds like the musicians are right there doing what they do best, so I recorded the band in whole takes, with everybody wearing headphones, so they could hear Michael, which was important to inspire them to a better execution and get a good take. There was no click. We set the tempo, and if the band was fluctuating or drifting, we'd regroup and try to pay more attention. I ended up with one particular performance that I felt was very well‑executed and just kept it. That was the take and it turned out to be big. There were no overdubbing edits, although I did later on use Pro Tools to make a few repairs. Players aren't perfect and they get tired. But I only did this when I felt that it was necessary to preserve the integrity of the performance, like tune a note if it affected the blend of the saxophones, for instance. I don't line up everything to perfection, because that would defeat the purpose of a live performance. Of course, I'll use technology if it is to my advantage. If players make minor mistakes, I can say, 'Don't worry, I can fix this,' and move on. You want emotion and you want feel and you want precision all at the same time.”

Mixing

The Neve desk at the Warehouse in Vancouver was one of three originally built to specifications laid down by George Martin and Geoff Emerick when they were developing AIR Studios in London and Montserrat.The Neve desk at the Warehouse in Vancouver was one of three originally built to specifications laid down by George Martin and Geoff Emerick when they were developing AIR Studios in London and Montserrat.

"When I am mixing, I am very hands‑on and manipulate the dynamics by hand. When you are producing, the vocal goes through three stages: recording, putting the pieces together, and mixing. I try to capitalise on the emotion in every moment, in a very musical way. You don't hear what I do and compression is not needed. People, particularly when working in Pro Tools, put masses of compression on. Everything is bang in your face, one‑dimensional. They sometimes sound brilliant on the radio, and sometimes awful because of all the radio compression that also gets added. I want my records to sound great anywhere.

"The first thing I do when I begin a mix is work on the vocal. I make it sound smooth and make sure the articulation is correct, and so on. I spend a lot of time making sure the vocal is in top shape, and I may use a little bit of Neve 33609 compression and my GML EQ — the GML is one of the most musical EQs ever built. Everything has to revolve and sound good around the vocal. When I've gotten the vocal to sound right, the foundation is there, and the mix becomes more fun and there is room to be creative and expressive with the rest of the mix. Let's see what we can do with the instrumentation. So, after that, I work on the rhythm. I'll then work on balancing the horns and saxophones, and the bones, and the strings. I get all the balances in perfect harmony and then I start having fun with reverbs and delays and whatever creative thing comes to my mind. By this stage, I have everything up in the mix. I then dismember it again, and verify the vocal against the rhythm section, the rhythm against the horns, the horns with the vocals, and so on, to see how everything works.

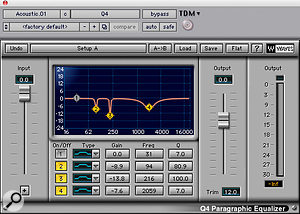

"The Session of 'You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You', consisted of about 46 tracks. I mixed the whole album in Los Angeles, at Capitol Studio B on the old Neve 8068 there. It's a fabulous studio with a wonderful sound. I ended up so pleased with all my mixes on Crazy Love. They're all fat and well‑defined‑sounding, with incredible punch. I did a few things in Pro Tools, just a compressor here and there to get things to sound tight and to have more control, and I used the George Massenburg EQ plug‑in to clean up some vocal proximity [low‑frequency boost] and straighten out some other things. Michael sang some of the vocals in Vancouver and some in LA, and I needed to match these. But everything else in the mixes was done on the desk and with outboard.

"As I said before, I'm not an in‑the‑box friendly guy. I don't care what you do and how much you want to use plug‑ins: trying to duplicate the sound of an 1176 or of a vintage EQ or whatever with them doesn't work. It's never the same. So the only way to approach it is to keep compressing and in the end you have this record that when you listen to it you are like… [makes sound of being throttled] You can't even breathe. Nothing is moving. Nothing is open. It's like an addiction. So instead I stick to the old‑fashioned way of making and mixing records, while also using the sounds that the new generation is used to hearing today. That's OK. I you use compression in a musical way, you can do a magnificent job and you have the best of both worlds. But you don't want to overcook things. There is some music a dinosaur like me will never be able to do, because those kids know how to manipulate bottom end. And with some of the modern singers you need all sorts of major effects and processing, it's the only way you can make it fly. But for the stuff that's done by great artists like Michael Bublé, Andrea Bocelli, Josh Groban, Celine Dion, the box is not the answer, the box is the beginning of the end.

"During recording and the mix, I worked hard on mixing the drums, because Michael really likes to hear the groove and the pounding of the drums. I use some EQ, often from my GML, and some Neve 33609 compression where necessary. With songs that I have recorded myself I don't need to do much in the mix, it's more just a matter of balancing and placing things in the stereo spectrum. I mainly use the GML EQ and the Neve 33609 compressor, but very sparingly. I had both boxes on Michael's voice, and some reverb, and another EQ, that I don't want to talk about. I'm supporting kids that go to college! Vocals and the drums are the most important aspects of a mix, and the arrangement as a whole. When you understand arrangement, mixing is easy. You know what you're looking for. Otherwise you're fishing.

The live room in Warehouse Studio 2, where the session was recorded.The live room in Warehouse Studio 2, where the session was recorded."I also spend quite a lot of time adding ambience and space to the mix. I have a very interesting approach, I mix things up. I use things that give me length, and I use things that give me width. I have a colourful way of mixing things. One of the first things that Michael Jackson said to me when I did my first mix for him was, 'Great, you work in colours.' And I said: 'It's my life.' For ambience I of course used the ambient tracks that I had recorded at the Warehouse, mostly from the M50. I used two other stereo pairs of mics, because I'd never worked in that room, and I wanted to cover my back. But there was a resonance in the air that was fabulous. I had the precision from the close mics, and then when you open up the room mics you get the depth. I also added some outboard reverb from the live chambers at Capitol. They were amazing. You can't top that. And my favourite reverb friend is the [AMS] RMX16. I love it, I love it, I love it, because I think it sounds very musical.

"I mix back into Pro Tools. After I finished the mix, I made stems of everything in Pro Tools. I'd make stems of the saxophones, the trumpets, the rooms, the bones, the drums, the snares, the vocal dry and the vocal with reverb. These stems are completely clean, they are impeccable. Once I'd dissected the song like that, I'd move with confidence to the mix of the next song. Once all mixes for the album were done, I come to what I consider the most fun part of my work. In my mind I become completely an outside producer who is evaluating all the mixes to see whether they are overproduced or overexposed or whatever. I'm very relaxed when I do this, and I may say: 'This part needs to go down a little,' or 'Let's get rid of that part, it's not needed.' I make sure that everything is breathing and that all the tracks on the album form a unity. So I'm truly doing touch‑ups, this is the final stage, and when it's done, I know I can go into mastering with full confidence.” .

The Humberto Gatica Story

"I came to the US in 1968, when I was 17 years old,” says Humberto Gatica, who grew up in Chile. "I was following my dream of a better life. It was interesting in that I had no fear. I just looked up north, and left. I borrowed some money and flew to Mexico, that's how far the money went, and then took a bus to California. I located some friends and started looking for any kind of job that I could find. I come from a musical family, so I was thinking of music, but I did not want to be a performer, even though I played a little bit of guitar. Then, in 1971 I accidentally walked into the MGM recording studio, to witness a recording. This had been arranged via a friend. From that moment on I was completely in love with the whole world of recording. The studio manager allowed me to become an intern, and I did everything from cleaning to changing lightbulbs.

"I gradually became an assistant engineer, and then one day in 1973 I found myself doing a live session organised by the producer Don Costa, who worked with Frank Sinatra for many years. The engineer for that was sick at the last minute, and it was too late to cancel the session, so Costa said to the studio manager: 'I'll take my chances with the kid.' It was a three‑hour big‑band session with 40 people, so my first recording experience was with a large band. I proved that I had the desire and talent to be able to handle sessions, and continued working as an assistant engineer with the same producer, who liked me very much. A year later MGM sold its studio business, and I was laid off, and I went independent. Things went very quick after that, and I won my first Grammy award with Chicago in 1984. I also worked with Quincy Jones and Bruce Swedien on Michael Jackson's Thriller and Bad, and the latter got me a second Grammy award for Best Engineer. I also won two Grammy Awards with Celine [Dion].”

Thursday, June 25, 2015

Wednesday, June 24, 2015

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: Justin Gerrish & Rostam Batmanglij

Inside Track: Contra by Vampire Weekend

Technique : Recording / MixingIn Contra, Vampire Weekend have made one of the more unlikely US hit albums of recent years. Guitarist Rostam Batmanglij and engineer Justin Gerrish explain how they wowed American audiences with African influences.

Paul Tingen

Justin Gerrish, who mixed 'Cousins', at Avatar Studios in New York.Justin Gerrish, who mixed 'Cousins', at Avatar Studios in New York.

Despite the success of Paul Simon's 1986 album Graceland, music with a strong African influence has rarely filled the hit parades here or in the US. Vampire Weekend have bucked the trend: their second album, Contra, stormed to the top of the American and Canadian charts on its release early this year, as well as hitting number three in the UK, in both cases feeding off the popularity of its lead single, 'Cousin'.

The band have described their direct, in‑your‑face sound as "Upper West Side Soweto”. One of the main men responsible for this musical direction is Rostam Batmanglij: as well as being the band's keyboardist, drum programmer, second guitarist, string arranger, engineer, mixer and producer, he also co‑writes most of their material with singer Ezra Koenig.

"It's great,” he says of their unprecedented success. "Ed O'Brien from Radiohead was at the show last night [the band are touring at the time of writing], and he mentioned that we were penetrating the mainstream in the same way as they had done. At the same time, we are not ignoring pop music. We love all kinds of music: African, classical, pop. You can make anything part of a pop song if you hide it enough. And certainly what we have done is fundamentally different from what Paul Simon did. We haven't gone to Africa to work with African musicians. We don't use existing traditional African chord progressions or structures. Our inspirations are more abstract.”

Elaborating on how Vampire Weekend give form to their inspirations, Batmanglij explains that "There is often no set labour division. We feed off each other. On many songs this is true for the whole band writing together, with drummer Chris Tomson and bassist Chris Baio contributing throughout the process. A big part of Vampire Weekend is the four of us working together in the rehearsal room playing our respective instruments, and working off of one another. Another part is Ezra and I working together. In some cases Ezra will start with something and it will inspire me to write another part and then he will come up with something on top of that. Ezra wrote all of the lyrics on Contra, though for 'Horchata' and 'Diplomat's Son', he and I wrote the lyrics together. Ezra may come in with a melody or a chord progression, and he and I will work together in front of an upright piano, and at other times, like with the songs 'White Sky' or 'Taxi Cab', the songwriting and production were very much integrated. I visualised the chord progressions, the instrumentation, even the drum sounds in my head, and then worked them out in Reason and Pro Tools. I immediately try to go for the finished article as far as possible, because I don't believe in demos and re‑recording. Not in this day and age. You will always try to recapture the magic of that first recording, so I don't do it.”

Hard Work

Mixing the album at Avatar. From left: singer and guitarist Ezra Koenig, Matt Herman (friend of the band), bassist Chris Baio, assistant engineer Fernando Loreido, Justin Gerrish, XL Recordings A&R man Kris Chen and Rostam Batmanglij.Mixing the album at Avatar. From left: singer and guitarist Ezra Koenig, Matt Herman (friend of the band), bassist Chris Baio, assistant engineer Fernando Loreido, Justin Gerrish, XL Recordings A&R man Kris Chen and Rostam Batmanglij.

Because bands have often had years to work on their first album without any interference or expectations from the outside world, follow‑up albums are synonymous with stress and pressure. Apparently, Contra was no exception. Batmanglij: "With this record, psychologically it was very hard for me to let go of it, because I had literally spent years working on the two records before it, the Discovery record [his side project with Ra Ra Riot's Wes Miles] and the first Vampire Weekend album. Whereas, with Contra, we started recording in January and we finished it by September. It was really important with this record for us that we satisfied our impulses to make complex, intricate music, but also to make pop music, to make catchy music, to make what we think of as hits. We were trying to reconcile those things, and that meant a lot of pressure. I never worked harder in my life.”

Vampire Weekend's debut album had been recorded by Batmanglij in different places — his apartment, a friend's basement — on Pro Tools LE, often using an M Box interface. For Contra, he wanted to work on Pro Tools HD and, as he didn't then have the money to buy a system (he finally acquired one early this year), much of the hard work for the new album was done at Treefort Studios in New York, which is owned by engineer Shane Stoneback. Before and during the writing and recording sessions at Treefort, the band occasionally dropped in at nearby Avatar Studios — famed for its large, wood‑panelled recording areas and vintage equipment — for rhythm-section tracking and, eventually, mixing. They were helped out at Avatar by young staff engineer Justin Gerrish, who has worked at the studio since 2005, and trained with studio luminaries Rich Costey and Russel Elevado, among others.

"For the new album, about half of the songs were played by the band before we started recording,” recalled Batmanglij, "and the other half we wrote and constructed in the studio. My method for recording is always to record the drums first, so we began by recording the drums for four of the songs at Avatar. Then we went to Treefort, which was a great place to be, because I could spend as much time there as I wanted. Ezra and I spent a lot of time there working on songwriting and production, while Shane would come in as an engineer, as and when we needed him. It was crucial to have our own recording space.”

Happy Sound

The Pro Tools Mix window for 'Cousins', with colour‑coded tracks indicating, from left, drums, bass, guitars and vocals.The Pro Tools Mix window for 'Cousins', with colour‑coded tracks indicating, from left, drums, bass, guitars and vocals.

"We didn't use a desk at Treefort, everything went straight to Pro Tools. I had bought a Neumann M149 when we started recording, and we also had a Neumann TLM103. These were our two main vocal mics. We also used the Shure SM57 on tons of stuff, especially guitar amps. There was a great old Silvertone amp at the studio that Ezra and I used for our guitars. The guitar tones on the first album were all Fender Deluxe; the new album is a combination of Deluxe and Silvertone sounds.

"After about a month of working at Treefort, we went on tour, and when we were in Mexico City we had some time off and decided to record some songs there. We ended up in the studio called Topetitud, owned by Tito Fuentes of the band Molotov. The studio also has Pro Tools HD, and Tito, who acted as engineer, had a bunch of API preamps and some outboard gear, like [Empirical Labs] Distressors, which he used on some of the snare tracks.

"One of the songs for which we recorded the backing tracks in Mexico was 'Cousins'. We recorded vocals, guitars, bass and drums to a click track. The drums were isolated in a pretty small, reflective room with lots of hardwood. The bass was in the control room and the guitars and vocals were done in another room. We recorded everything live and then re‑recorded on top of a comp of the best drum takes. Because the snare is such an important part of that song, I remember putting a couple of microphones on it, so we could pan it later on and make it as wide as it could be. We did the drums on the first day, and the next day we recorded bass and guitar. Tito had this awesome white double‑necked [Gibson] SG, and we used the 12‑string neck to record some of the guitars. That initial guitar that you hear on the track is played by Ezra through a Roland Jazz Chorus JC120, and I am using the chorus on the amplifier and miking the amp in stereo, one microphone for each speaker.

"The track is very fast, and Chris and Chris wrote some of their most challenging parts as a rhythm section. Although almost everything is played, we did one real studio trick. We wanted some of the guitar parts to sound robotic and mechanical and plasticky, in the way that a lot of Mexican and Puerto Rican guitar tones are. So one riff was played at half speed, and using Pro Tools, we squeezed it in time exactly by half. Most of the guitars in this track were played by Ezra, but the bells part that comes in at the end was something I initially wrote on guitar, and was trying to put it on top of one of the verses. It was supposed to be like a Bob Dylan kind of guitar lick, but then I had a vision that it could sound like church bells at the end — coming in over what Chris and Chris called 'the Rage part', their tribute to Rage Against the Machine. So in one speaker there are tubular bells, and in the other speaker a celesta, and in the middle you have my distorted guitar line. This was all done in Mexico.

Ezra Koenig playing the double‑necked Gibson SG that provided many of the guitar parts on 'Cousins'.Ezra Koenig playing the double‑necked Gibson SG that provided many of the guitar parts on 'Cousins'."After we came back to New York, we continued work on 'Cousins', and the last thing we recorded was Ezra's voice, using the M149, and I had that going into a Distressor. I'd heard Justin use it in Avatar and liked the way it affected the drums. I maxed out all the buttons on the Distressor to get a lot of natural distortion. Everything on our first record was recorded very cleanly, with any distortion happening in the box. On Contra, I broke out into using analogue gear for the first time, and on Ezra's vocals there are some moments where you can hear the overtones more than the fundamental. I'm really happy with that sound.”

'Cousins'

Written by Biao, Batmanglij, Koenig, Tomson.

Produced by Rostam Batmanglij

Batmanglij: "The way I work is that I am slowly mixing while recording, because I want the track to sound good. So for all the mixes on Contra it was a matter of Justin and I completing what I had already started. 'Cousins' was the one exception. We had a lot of distortion happening when we did rehearsal recordings of the song, and I realised that it would need tons of distortion in the mix as well. I'd done my best to achieve that in the box, but I was not happy with it. We'd already started mixing some of the songs and Justin clearly had a sense of what we liked, so I asked him to have a shot at mixing 'Cousins' alone. As a result, he was not starting from where I had left off, and instead did his own thing — which was nice, because he was able to use a lot of outboard gear. We then worked together on the track from there.”

Justin Gerrish takes up the story: "Rostam wanted to do all the mixing himself, but after the first day of mixing here at Avatar, he asked me to help him out. While recording, he'd already been building his mixes the way he wanted, and only a few of the songs changed drastically in the last stage. 'Cousins' was one of them. I think it was the second song we worked on, and he said that he didn't really know what to do with the mix, but that the other band members liked it and so could I have a go while he went out for a bit. When I heard the track, I felt that it had a very raw vibe, and that it would be nice to take it more into that direction, doing it almost like a punk song, very minimal, not very glossy or pristine‑sounding, but rather vibey and edgy. When Rostam came back later, he said it was the first time that he really enjoyed listening to the track.”

Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: Justin Gerrish & Rostam Batmanglij"'Cousins' is a raw track, and I added more distortion to some of the vocals and other instruments, but you can't distort plug‑ins in the same way as you can distort a piece of analogue gear. There are saturation plug‑ins that get close to the real thing, but if I'd tried to do all the distortion with plug‑ins, it would have sounded thin and I'd have had some popping and clicking. However, the band wanted to mix primarily in the box, so we could pull up any song at any time and work on it. Sometimes we'd work on one song for a couple of hours and then we'd open up another one. I therefore had to use hardware inserts for the outboard, and setting up routings for that obviously takes more time than just dialling up a plug‑in.

"Personally, I prefer working on a desk, because I can get sounds a lot quicker, and also, I find it harder to get the same spatial depth when working in the box. A certain distance between the instruments is a lot easier to achieve when working on a console. I don't know why. Perhaps it's to do with the physical act of holding a fader or pan pot and moving it ever so slightly until it feels right. When you're mixing in the box it's also hard to ignore the visual aspect of it, because you're staring at a screen the whole time, instead of paying attention to what you're hearing. While I was mixing 'Cousins', I started working with the Mackie Universal Control, but it ended up frustrating me more than anything, because the faders didn't respond right away and it never reacted like an SSL or a Flying Faders system. In the end I used it only for the transport buttons.

"When I start mixing a song, I normally listen to the rough mix first to get an idea of what the band has been listening to, and I then push up all the faders and get a quick balance, without doing any EQ or processing, just to hear what's there and how it all sounds together. Next, I work on the drums for a while, and then the bass, and after that I'll throw the vocals in to hear how they'll sit with the bass and drums. Then I'll mute the vocals again and add the guitars and keyboards. Once those are sitting nicely, I'll throw in the vocals again to check how they fit, and so on. In the case of 'Cousins', the first thing I focused on was how to get the bass and the drums to gel together. The tracks from Mexico were a little different from those that had been recorded at Avatar and Treefort, and it took a little longer to get them to sound punchy and present. There were a couple of stereo mics that had different levels between left and right, perhaps because of a bad cable or something, and I ended up splitting these and putting them on separate tracks. 'Cousins' is a very fast song, with the bass and drums being very active throughout, so I wanted to make sure that there was a lot of clarity between them and that they locked together, so that other elements would not be obliterated by a mass of low end. After that I brought the guitars in, which are also doing a lot of fast lines, and then I worked on marrying the vocals with the foundation I had built. It was sounding a lot rawer and edgier than 'Holiday', the first song we had mixed, so I really was not sure whether they would be into this sound or not.”

Drums: NI Battery, Waves Renaissance EQ & Q4, Bomb Factory BF76 & Fairchild 660, Digidesign EQ III & Expander/Gate III, PSP Vintage Warmer, Neve 33609, URS 610.

Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: Justin Gerrish & Rostam Batmanglij

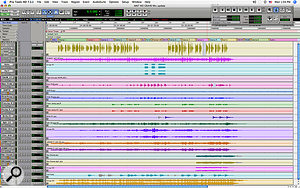

Gerrish: "On the far left of the Mix window screenshot for 'Cousins', you can see the 'SnrTr' track, which was a snare-roll sample I loaded to help the song going into the choruses. I used the [NI] Battery sampler, which is on the track next to it, and the track next to that, 'Mstr1', is my stereo mix. To the right of that are all the main drum tracks. 'BD09' is the main bass drum track, which has quite a few plug‑ins, including the Renaissance 4‑band EQ, Digidesign EQ3, Waves Q4, and the Bomb Factory BF76 compressor. I find that I'm never really satisfied when I try to get the entire sound from one EQ, so I tend to use different EQs, each doing one thing. The '4409' track is another bass-drum mic with two EQ plug‑ins (I didn't use the greyed‑out plug‑ins). Then there are five snare tracks: 'SN09', 'BPRI' (the printed snare sample), '4210' (another snare mic), and 'snr05' (a pair of clean sidekick sounds), with Renaissance, Waves, and Digidesign EQ plug‑ins and the PSP Vintage Warmer, Expander/Gate III and a Fairchild 660 plug‑in.

"To the right of the snare tracks are two tom tracks, with the Expander/Gate and a Renaissance EQ, and then 'SF09' and 'SFPRI' are the result of a stereo track that I got in the Session, which was called SF and which I assumed to be a Royer SF12 stereo ribbon mic. I wasn't sure if it was supposed to be a room mic or an overhead, because the two sides of the mic were not even — the left side was 12dB lower than the right and closer‑sounding. I split the track into two mono tracks and treated them differently, turning one into an overhead and the other into a room mic. I ran the 'SF09' track through my [Standard Audio] Level‑Or 500‑series outboard compressor, which is pretty noisy. I tend to use it as a distortion box. The '4211' next to that is the snare top mic, which I had duplicated to be able to treat it a little bit differently, using, again, EQ and PSP Vintage Warmer.

"The three yellow tracks to the right of that are for parallel compression. When I'm mixing drums, I like to use parallel compression so that I can get attack and punchiness but not lose the body of the sound by over-compressing the individual tracks. For the parallel compression in 'Cousins', I created a separate set of sends in Pro Tools, sent that to an outboard Neve 33609, and then had that return on a stereo track, called 'DComp'. Once I was happy with the sound, I printed the compression track so that I wouldn't have to recall the settings and we could keep the workflow going. I also had some plug‑ins on the parallel compression tracks, including the Bomb Factory 1176 and the URS 610, which works like an API 560 EQ.”

Bass: Bomb Factory BF76, Neve EQ, Empirical Labs Distressor.

"There are five bass tracks. The first three are the original recorded tracks, which include a DI and an amp track. Chris Baio's bass line in 'Cousins' is constantly moving. He's not just playing roots, so I needed to make sure that you could hear the articulation in his playing, otherwise the song would have lost some of its momentum. I ended up compressing his bass DI quite a bit with the BF76 to keep all the notes even, but left the amp untouched. I then bussed those two tracks together so that I could EQ and compress them as one bass, which I then sent out to a hardware insert on which I had a Neve EQ and a Distressor. The two other tracks are just the bass for the bridge section.”

Guitars: Waves Q4, Digidesign EQ III, Bomb Factory SansAmp PSA1 & BF76, Digidesign Pitch.

"There are 15 guitar tracks. You can see on the screenshot that I colour‑coded them. This was to group and show the guitars that worked together, such as intro guitars, verse guitars, and so on, and therefore should be treated in a similar way. 'RG' are Rostam's guitars, the rest were played by Ezra. Most of the guitars were recorded with a close mic and a room mic, which allowed me to create an ambience in the track without using any reverb. In fact, the only reverb used on the whole track was a live chamber on the 'ooh ah' backing vocals in the first half of the bridge. In the same section, there are two guitars doing 16th‑note picking, and when I first put them up, it reminded me of a sonar ping that you hear in the movies. So I tried to get them to sound like they were in a submarine or underwater, something in that realm. For the rest of the guitars, I wanted it to sound like it was a garage band playing with the front door wide open, pissing off all the neighbours on the block. The plug‑ins I used were for the most part EQs, although the SA1 on 'GT11' is a SansAmp plug‑in, to give it some more bite and edge. To the right of these 15 guitar tracks are two tracks called 'rsnbl' and 'rsnb1', which are Rostam's tubular bells and celesta towards the end of the song.”

Batmanglij: "For one of my guitar tracks, I used the Digidesign Pitch plug‑in to double my part an octave higher. This made it sound like a horn, and it comes in right before the drums drop in. The track also comes in right before the 'Rage part' begins and where it sounds like an Appalachian fiddle.”

Vocals: Universal Audio LA3A & 1176, Standard Audio Level‑Or, Digidesign Pitch, Bomb Factory BF76.

Gerrish: "'LV' is the lead vocal track, of course, and the only thing that seemed fitting for Ezra's vocals was to get them to sound more crunchy. To achieve this, I had two EQs on the track, and then 'VoCh' is the bus towards an LA3A and an 1176. I printed that on the adjacent track, bussed that to a Neve mic pre, then compressed it with a Level‑Or, and then returned that to Pro Tools. I ended up blending this distorted signal with the clean vocal to give it more bite. 'Awawy' are the high‑pitched vocals at the beginning that sound like a monkey, and 'Voc FX' are the bridge vocals, with effects being the Pitch plug-in and the BF76 compressor. 'CPRIN' is the print of the live chamber for the 'ooh ah' background vocals.”

Master bus: Universal Audio 1176, GML EQ, Massey L2007.

"I printed the final mix back into the 96/24 Session and used some outboard on the master fader, such as an 1176 and GML EQ, and I also used a Massey L2007 [limiter] plug‑in on the track.”

Batmanglij: "What's interesting about the way we worked is that when we took Contra to mastering, with Emily Lazar at The Lodge in New York, we worked with stems and did even more stuff to it. So we'd print the stereo mix, and then stems of the drums, bass, vocals, guitars, and so on. Things got very hectic towards the end, and we'd already started mastering songs when not all the mixes were finished, and used the mastering process to finalise a lot of songs. For some songs, I simply gave Emily the stereo mixdown but, for instance, with 'Cousins' I felt that we could bring out the guitars even more, so we brought up the guitar stem and put a Waves S1 imager on it. Emily also had a Dangerous Sum & Minus unit, which allows you to change the stereo image. It basically widens everything up and clears up the bottom end. I became addicted to it [laughs], but it also changes your mix, so in using it we had to go back and revise the balance on a number of songs.”

Monday, June 22, 2015

Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: Cenzo Townshend

Inside Track | Florence and the Machine: ‘You’ve Got The Love’

Technique : Recording / MixingFlying the flag for a distinctively British sound, and scoring some huge hits in the process, Cenzo Townshend is one of the UK's hottest mixers. He gives us the inside track on Florence and the Machine's hit 'You've Got The Love'.

Paul Tingen

Cenzo Townshend in his mixing room at Metropolis. Note the scribble‑strip curtains!

Many of the American mixers featured in SOS's Inside Track series have explained that they pay little attention to rough mixes, preferring to start from a clean slate. Cenzo Townshend, one of the UK's leading mix engineers, takes the opposite approach. "I don't subscribe to the view of not wanting to hear the rough mix. I am here to represent what the band and the producer want from a project, not to completely start from scratch and do my own thing. It is not my record. If people want me to take a song in a different direction and want my input, great, but most of the time my job consists of giving the best possible rendition of the vision that they have. So I spend a lot of time listening to their rough mix, or the monitor mix that they like the best, to hear where they're at.

"Because recording budgets are so small now, a lot of records are recorded in private rooms, often with laptops. In these circumstances people haven't really been able to hear what they're doing and haven't been able to properly balance things; I therefore spend a lot of time cleaning sessions up, organising and editing. But they do have a vision, so my job is to work as closely as possible with the artist and producer to find out what they like about their own mixes, what they have been able to achieve and what not. Many people love their monitor mixes, but there will be things that they felt they never got right.”

Alone With The Music

Townshend's mix room is based around an SSL G‑series console, with KRK 9000 and Yamaha NS10 monitors.

Townshend must be getting a lot of things right, judging from the long string of hit records he has worked on. The list of artists he has helped includes Bloc Party, Interpol, Babyshambles, Editors, Jamie T, Graham Coxon, Friendly Fires, New Order, Klaxons, Kaiser Chiefs, Snow Patrol, U2, Franz Ferdinand and many more. Cenzo Townshend (his first name is an abbreviation of Vincenzo — he has a half‑Italian father — and the 'C' is pronounced 'cz' as in Czech Republic) began his career in the late '80s at Trident Studio in London, working his way up the usual studio greasy pole, starting as a tea boy and then becoming assistant engineer for legendary studio professionals such as Flood, Alan Moulder and Mark 'Spike' Stent.

Townshend subsequently went independent, working for eight years with producer Ian Broudie before joining producer Stephen Street at The Bunker, located at Olympic Studios in London. Having spent the best part of two decades mainly engineering and occasionally producing, the last five years have been devoted 95 percent to mixing. "Obviously, there is a larger need for mixers these days than there is for recording engineers. But it also suits my personality. I like to be left alone to get on with things. Also, mixing is all about attention to detail and balance, you have to have the mind-set to be able to concentrate and go through all the mundane stuff before it comes together. A mixer is basically a balancing engineer with an aptitude for detail and an interest in sound.”

Townshend's achievements were recognised last year when he received the Music Producers Guild's award for Best Mix Engineer, and his prominence means that he mixes "a lot of singles, especially for radio. This is slightly different than mixing for an album. It means that everything has to sound a little bit more exciting and bombastic and has to jump out a little bit more to compete with the other things that are on the radio. Something that I am also aware of, but can't do much about, is the frightening fact that the same song will not only sound different on different radio stations, but sometimes will sound different on different days or even times on the same radio station! XFM went through a period of sounding harsh and brash, but now sounds better than Radio 1. Radio 2, for some reason, sounds fuller and bigger than Radio 1. Meanwhile, Radio 1 seems to sound better at night-time than in the day. In LA the radio always sounds brilliant. I don't know why this is, it's probably to do with the different compressors they are using, but no‑one seems willing to volunteer any information.”

After a long residency at Olympic Studios, Townshend moved to Studio B at Metropolis in February 2009, following Olympic's closure, something that clearly still rankles with him. "It was due to the whims of EMI, and it was very unfortunate, because it was one of the last great recording studios in the world. Amazing records were made there, and I feel that we lost a lot of the heritage of British music. With that, I think we're losing the sound of British music. It's all being watered down, and I'm concerned that we'll be completely overrun by American music and everything will sound the same. So I'm a great advocate of keeping that British sound going.”

Machine Made

A small selection of Cenzo Townshend's vast array of outboard, including several items used on his mix of 'You've Got The Love'. From top: Manley Vari‑mu compressor, Empirical Labs Distressor compressors (x4) and Fatso tape emulator, Summit EQP 200B equaliser, SSL XLogic compressor, NTI EQ, Smart C2 compressor, Chandler/EMI TG1 limiter and EAR 660 compressor.

One of Townshend's most high‑profile projects recently was Lungs, the debut album from Florence and the Machine, most of which he mixed. It was released in the middle of 2009 and is still a big seller, recently hitting the top spot in the UK charts for the first time. Townshend mixes included the last three singles, 'Rabbit Heart (Raise It Up)', 'Drumming Song' and the top 10 hit 'You've Got The Love'.

The last is unusual for the band, in that it's a cover of a song by The Source (featuring Candi Staton), first released in 1986 and a UK hit in 1991. Florence and the Machine's cover was initially a 'B' side, but following widespread critical praise, Universal Island decided to re‑release it as a single in its own right. For this reason, Townshend ended up mixing the track twice.

"It's a song that she had been singing live for a while, and everybody really liked it. After three successful singles, the record company was looking to release it as a single, and she came in here and did about five or six new vocal takes. She was fantastic. I recorded her with a Neumann valve 47, going through one of my Neve preamps, then into an 1176 and via my Lavry Gold A‑D converter into Pro Tools. We then sat together and decided which bits to use. We didn't do much comping, and only replaced the first two verses and the first chorus. I think from the second chorus onwards we kept the original vocal. I then basically remixed the whole track from scratch, though the only real differences in the single version are the new vocal, and the bass and drums are a bit harder and the bottom end a bit heavier.”

Making Preparations

Townshend's upstairs preparation and post‑production room, featuring the SSL Duality, a Pro Tools HD3 system and several monitors, comes into its own the moment a project arrives for mixing. "The first thing that happens is that Neil Comber, my assistant engineer, will prepare the session for me, cleaning it up and laying it out in the way I like. Sometimes the session will come in as a Logic file, and Neil will have to build a Pro Tools Session from it, which can be quite laborious. We have to check every edit as we transfer things to Pro Tools. Sometimes there are 120 tracks to go through! During mixing later on, I'll have the Logic session on a separate computer somewhere for me to refer to and to see if they used any particular kinds of plug‑ins, panning, balances and so on. Even when we get a Pro Tools file, we often receive just a bunch of files without having any idea what they are. Tracks may just be called 'Audio 1', 'Audio 2' and so on, and we'll have to work out what's what. If sessions have been FTP'ed we also need to check that we have the right amount of tracks, and so on. Sometimes the sessions are so big that they won't play. Pro Tools won't play more than 96 tracks at 96kHz, and to compensate people may have been bouncing and so on, and then we have to deal with that.

"Quite often, Neil will also add five or six snare-drum samples and three to four kick‑drum samples and kick-drum ambiences, and he'll time those to make sure they're accurate for each hit. We'll talk beforehand about what samples to add. Basically, they are there to beef up the existing kick and snare, if necessary. I don't replace kick and snare drums, and probably 50 percent of the time I'll decide that the kick and snare I have are so good that I don't need to add anything. The reason he adds them at this preparatory stage is that I don't have the time to start adding samples when mixing, because we only have one day to mix a song. So Neil will add them in case we need them. All in all, Neil usually has three hours of work to do before I can actually begin the mix.

"The samples I use are usually things I've recorded over the years. But I'm not purist about it. If I hear a good sound somewhere, whether from a library or from something else, I'll borrow it. I have quite a few sample libraries, but you have to audition the sounds, and I don't have the time to listen to hundreds of samples. Neil uses the Drumagog plug-in to trigger the samples he adds, but you still have to go through each hit and move it in time to make sure it's 100 percent correct and the phase is correct. You look at the waveforms, but you also need to use your ears. Time‑alignment software is very time‑saving, but the drawback remains that it's not as good as doing it manually. I also use the Aptrigga2 plug‑in, which is great for things like tambourines, because it's a little random, and you don't want to have tambourines bang on time. Sometimes we spend as much time trying to slightly offset things to make them sound more natural as trying to get them to sound exactly in time.”

'You've Got The Love'

Written by Anthony B Stephens

Produced by Charlie Hugall

"'You've Got The Love' came in as a Pro Tools file with some of the effects already present. Her vocals were slightly distorted with a Fairchild plug‑in. It's not a very big Session by modern standards, though it has many rhythm tracks. The first thing I do when I get the Session from Neil is to spread it out over the board, and then I'll do my best to get the song as close as I can to the monitor or rough mix — within reason, I'm not going to obsess over it. I'll reference the band and/or producer's favourite monitor mix to get a balance, and while I'm doing that I'm getting to know all the parts that make up the song and getting a sense of what I'm trying to achieve with the song. In the case of 'You've Got The Love', the tricky aspect of the mix was the interplay between the guitars and the harp. The harp plays a huge part, melodically and rhythmically, and to get the harp and guitars to bounce off each other in the right way needed quite a few plug-ins and limiters.

"Having got to know the song in an hour or so, I start moving things around and begin to find the right compressors and EQs, for individual tracks and also for the stereo mix. I'll then get the vibe of the bass and the drums working, and may fire things through the live room here in Metropolis to record various ambiences for the kick, snare and toms. We have various speaker setups with ribbon mics to pick up the ambience. Among other things, I have an Auratone speaker on top of a snare drum, and I'll send the signal through the Auratone, which hits the drums, and this is picked up by two Coles ribbon mics. The room is also great for re‑amping guitar to get some guitar reverb, so I may spend a little time firing guitars, or the vocal, through the live room as well.

"Because I initially try to get the balance back to where it was originally, I don't tend to solo too much. But I will try to get the drums to sit well with the bass first, so I know what the rhythm is doing, and then add the vocal into that, and then the other instruments. I'm also constantly checking whether everything is in phase. Even if you think everything is OK, you may be halfway through mixing the song, and then you put your bass in and suddenly it's not sitting well with the kick. So you may have to flick the phase on the bass to make sure it has the same polarity as the kick drum. I tend to do that on the desk. There are various Trim plug‑ins on the Session, and they generally are for phase as well. Also, although there are many drum tracks, in the final mix it doesn't sound like you are listening to a huge rhythm track. That's very important.”

Drums: Audio Ease Altiverb, Waves Audiotrack, Massey CT4, Tapehead & EQ, EMI TG1 (hardware) & EQ (plug‑in), Sound Toys Echoboy, Digirack Expander/Gate & EQ, Eventide H3000, desk EQ & compression, Empirical Labs Fatso, Bomb Factory Sansamp PSA1. Sound Toys' Echoboy is one of Townshend's favourite plug‑ins, used here for a short delay on a snare track.

Tambourine: "There are two tambourine tracks at the top of the Session. There originally was one played track, which I copied, so I have two tracks with the same audio and different treatments. One of them I put through some guitar amplifier modelling, the Altiverb plug‑in on a 'Fender Superstring' setting, then a Waves Audiotrack plug-in for compression and EQ, and then a Massey compressor. Massey is one of my favourite plug‑in makers. The other track also goes through an Altiverb set to a room sound called 'Cello Studios', again Waves Audiotrack and then Massey Tapehead. Just below the tambourines is a snare track, put there to make sure the tambourines are in time. Normally, the snare tracks are further down. The 'stone room' track [Townshend is referring to the track naming in the Pro Tools Session, which there is not space to reproduce here!] is the Auratone sitting on a snare drum in my live room.”

Kick: "There are nine kick tracks. Neil added 'Polekick', which is a kick ambience sample, and 'Meat' and 'Limrock', which are kick samples. 'Polekick' is a trailing thing that adds a little bit of space around the kick sound, and you can EQ it to give a feeling of more low end without there being too much attack, so it doesn't flam with the real kick drum. Immediately above the real kick drum are two kick comp tracks, which trigger an Expander/Gate [plug‑in] that is advanced in time. By advancing the track and sending it to a side‑chain of the gate, it opens faster and without any strange artifacts in the sound. There are two more kick mics, called 'BD23' and 'NS10', and [tracks] two master faders for all the kick tracks. All the kick tracks go up and down in level in different places, so the balance between them varies. I do this in the computer. On the desk I'll have two kick channels: the real kick on channel one, and the samples on channel two. In terms of treatments, the real kick and the 'Punchy Room Kick' both have a Trim and a Massey three‑band EQ. On the desk I'd have EQ'ed the kicks, and they would have been bussed to an EMI TG1 compressor.”

Snare: "There are seven snare tracks, with a sample that's added by Neil, and some snare samples that remained from the Session as I received it. I didn't use the latter. Again, I created a balance of snare sounds that changes over the course of the track. In terms of plug‑ins, a number of the snare tracks, again, have a Trim plug-in, and on the 'snare comp' track there's also an Echoboy with 90ms delay and a seven‑band Digidesign EQ, pulling out 18dB at 500Hz. There was a peak there that I didn't like. Like the kicks, the snares would come up on two faders on the desk, on which I use SSL channel compression and, again, the EMI TG1. For ambience, I would have added the stone room, via the Auratone into the Coles, coming back into Pro Tools via a pair of Neve mic preamps. There's also some Eventide H3000 ambience on the snare, set to a room with very short reflections.”

The rest: "There's nothing on the hi‑hats, except desk compression. The toms have an EMI EQ plug‑in over the master fader. The overheads go through an Empirical Labs Fatso that's inserted on a channel on the desk, no plug‑ins. I have a Massey plug‑in compressor on the cymbals. After that is a room track that I duplicated, with one side being sent through a Sansamp PSA1 plug‑in and an Expander/Gate. I probably panned these two room tracks hard left and right.” Massey's CT4 compressor was used on the cymbal track.

Bass: Waves Q4, Digidesign Recti‑Fi & Lo‑Fi, re‑amping, EAR 660, Pultec EQ.Digidesign's Recti‑Fi plug‑in helped to shape the bass sound.

"There's only one bass track, which has a Waves Q4 EQ taking out a hump at 209Hz, because the bass was boomy, and the Lo‑Fi to add distortion, plus Recti‑Fi to twist the sound a bit more. If you have something incredibly noisy you can take the top off and add some distortion to the mids with the Lo‑Fi, which works great. The Lo‑Fi is a great plug‑in, and it's not just for 'lo‑fying' stuff. The Recti‑fi is a stranger beast, with which you can do some ridiculous things, like robotic distortion and ring modulator‑type things. The bass came up on two channels on the desk, and one of them I sent to my Hiwatt amp, for a warmer sound and some distortion. I have a Little Labs phase tool that interfaces the Hiwatt with the Sequis speaker simulator, which is amazing. I've gone through dozens of speaker simulators, and the Sequis is the best. The other bass channel went through an EAR 660 compressor and a Pultec EQ. So I had two completely different bass sounds on the desk, which I blended throughout the song.”

"There's only one bass track, which has a Waves Q4 EQ taking out a hump at 209Hz, because the bass was boomy, and the Lo‑Fi to add distortion, plus Recti‑Fi to twist the sound a bit more. If you have something incredibly noisy you can take the top off and add some distortion to the mids with the Lo‑Fi, which works great. The Lo‑Fi is a great plug‑in, and it's not just for 'lo‑fying' stuff. The Recti‑fi is a stranger beast, with which you can do some ridiculous things, like robotic distortion and ring modulator‑type things. The bass came up on two channels on the desk, and one of them I sent to my Hiwatt amp, for a warmer sound and some distortion. I have a Little Labs phase tool that interfaces the Hiwatt with the Sequis speaker simulator, which is amazing. I've gone through dozens of speaker simulators, and the Sequis is the best. The other bass channel went through an EAR 660 compressor and a Pultec EQ. So I had two completely different bass sounds on the desk, which I blended throughout the song.”

Guitars: Digidesign Lo‑Fi, Waves Q4, Neve 33609, Roland Dimension D, Manley Vari‑Mu, Empirical Labs Distressor, Eventide H3000.Townshend used Digidesign's Lo‑Fi to darken the acoustic guitar sound, and Waves' Q4 to notch out problem frequencies.

"There's one acoustic guitar track, on which I had the Lo‑Fi to make it less shiny. I'm not too keen on overly sparkly acoustic guitars in a mix, I prefer a more Kinks‑like, old‑fashioned sound. There's also a Waves Q4 notching something out. Outboard was the Neve 33609 and Dimension D chorus.

"There's one acoustic guitar track, on which I had the Lo‑Fi to make it less shiny. I'm not too keen on overly sparkly acoustic guitars in a mix, I prefer a more Kinks‑like, old‑fashioned sound. There's also a Waves Q4 notching something out. Outboard was the Neve 33609 and Dimension D chorus. "The two electric guitar tracks are the same part recorded with two mics, and had no plug‑ins. On the desk, I sent them to a Manley Vari‑Mu, and I would have set up some parallel compression channels with two Distressors. I also had the same H3000 ambience on the guitars that I had on the snare. I have no problems sending five different things to the same ambience. You get more of a unity of sound that way. I don't like using too many different delays and reverbs, because things can end up sounding very separate and lacking in cohesion.”

"The two electric guitar tracks are the same part recorded with two mics, and had no plug‑ins. On the desk, I sent them to a Manley Vari‑Mu, and I would have set up some parallel compression channels with two Distressors. I also had the same H3000 ambience on the guitars that I had on the snare. I have no problems sending five different things to the same ambience. You get more of a unity of sound that way. I don't like using too many different delays and reverbs, because things can end up sounding very separate and lacking in cohesion.”Harp & piano: Waves Renaissance Axxe, Renaissance Bass, SSL G‑series compressor & Q4, Sound Toys Echoboy, Massey 2007, Neve 33609, Bricasti M7.

"The harp had the Renaissance Axxe compressor, an Echoboy doing 16th‑note delays, and the 2007 Massey limiter. Outboard was the Neve 33609 and a Bricasti M7 on a plate setting. The Bricasti is £2000 worth of reverb, and while people may think that's mad, it does a few things incredibly well. The processing power in one of these boxes is 10 times that of a Mac and the calculations it can make are frightening. It does sound like an analogue reverb and it's one of the best reverb boxes you can get.

"There are two piano tracks, low and high, and on the low one I had the Renaissance Bass plug‑in to accentuate the low end, like a sub‑harmonic synth, and the Waves SSL G‑series master bus compressor plug‑in. On the high piano I have the Q4 to notch out at 750Hz and, again, the SSL compressor. Pop pianos require quite a bit of work to sit well in a track and for people to be able to hear them.”

Vocals: Massenburg EQ, Waves C4, Q4 & De‑esser, Bomb Factory Fairchild 660, Teletronix LA2A, Pye compressor, Dbx 902, Pultec EQ, Bricasti M7, Ibanez delay, Empirical Labs Distressor, Sound Toys Pitchblender & Echoboy, Massey Tapehead.Among the many plug‑ins used on Florence Welch's vocals were Massey's Tapehead tape simulator and Waves' Q4 equaliser. Sound Toys' Pitchblender was used as a vocal effect.

"The main lead vocal track is called 'LV Comp', with a track with some chorus doubling just below it. I treated both tracks the same way. I have a Massenburg Designworks EQ plug‑in on them, taking out 6dB at 1.5k and boosting at 5k. Then there's a Waves C4 multi‑band compressor, and a Fairchild plug‑in on the master fader [of the vocal group] which adds a bit of distortion, to make it sound more crunchy. On the desk I will have used an LA2A or a Pye compressor, a 902 de‑esser, and Pultec EQ. I added some reverb with the Bricasti M7, on the same plate setting as the harp. I also added various analogue delays using my Ibanez rackmounted guitar delay. In addition, I will have set up some parallel compression channels for the vocals with my Distressors. Under the master track are two vocal effect channels: one had the Pitchblender, which is an automated harmonising delay, and the other is an Echoboy with an automated eighth‑beat triplet delay. The next three tracks are all backing vocals, with just a Q4 EQ on the master. Across the board I would have had two Distressors on them and they would have gone to the same effects as the main vocal. Finally, there are two end backing vocal tracks, which have a Waves de‑esser and a Tapehead. I used the Waves de‑esser because I didn't have any more 902s. The Waves de‑esser is fairly broad and works fine for backing vocals.”

Strings: Waves C4, NTI EQ, Bricasti M7, TC Electronic D•Two.Waves' C4 multi‑band compressor was used to darken the string-machine sound.

"There are four stereo string tracks from a string machine. I have a C4 across the master fader to get some of the high end out. Outboard was the NTI EQ, which has this great thing called Air band that adds space in the high frequencies. The strings would also have gone to the Bricasti plate, and I would have used my TC Electronic D•Two stereo spatial delay, for a little bit of swirl. You'll find that the more acoustic instruments go to plates and lusher reverbs, while the more electric‑sounding stuff, like electric guitars and drums, tend to go to something a little harder and shorter.”

Final Mixdown

"The session was in 96k, and I recorded the stereo mix on another Pro Tools rig, again at 96k, going via my Lavry Gold A‑D converter, and through Analogue Tube AT101, which is a copy of the classic Fairchild 670 stereo limiter/compressor. It's made by Simon Saywood here at Metropolis, costs close to £14,000, and it's amazing [see www.analoguetube.com]. It's huge‑sounding and has valves at every stage. It's taken him four years to develop, and it sounds fantastic. I had it on the inserts of the master fader on the desk. I've used it on all sorts of records — U2, Editors, Detroit Social Club, all of Florence, and so on. Do I take the MP3 and other user formats into account when mixing? Well, I do make MP3s of my mixes, to send to the artists and producers, so I make sure it sounds good in MP3, but I don't mix for MP3. Otherwise it'd be useless to have a rig running at 96k using ridiculously expensive converters and clock sources. I'll always mix in whatever the highest possible quality is.” .

The British Sound & Radio Mixes

In last month's Inside Track feature, Cenzo Townshend's former mentor 'Spike' Stent noted differences between American and British mixes, in his opinion mostly to do with the way the low end is handled. Townshend picks up on other contrasts: "I think British music is edgier and more natural. I have nothing against American music, some of it sounds amazing, but a lot of it does get over‑polished and sanitised. I think English music as a whole has more aggression in the mid‑range, especially in the guitars. The guitars tend to be softer and more perfect and polished in American music. With a few exceptions, American rock guitars tend to sound very similar. Their bass sounds are fuller and rounder and cleaner, whereas I like bass sounds to be quite dirty; that gives more attitude, depending on the track, of course.

"In general, American musicians also tend to be accomplished players, often playing in more than one band to craft what they do over a long period. Whereas in Britain, being in a band usually is about four or five people making a great noise, the whole being greater than the sum of the parts. Sadly, commercial music is no longer about experimentation or even approximating the experience of hearing a band in a room play. Instead, commercial music is about trying to make a song sound as loud as possible on a radio, and people then downloading it onto their MP3 players. So why do I choose to focus on mixing for radio? Well, I love the radio. I have always listened to it and used be a DJ before I started working in studios. I like pop, and I like hearing it on the radio. I still listen to radio all the time; it's not just for work.”

The Best Of Both Worlds: Cenzo Townshend's Mix Room

The vocal overdubs and mix for 'You've Got The Love' took place in Cenzo Townshend's room at Metropolis Studio B, which features a 72‑channel 4000 G‑series SSL. It is apparently, one of the few piece of kit there that are not the mixer's. According to Townshend's web site, he's known for "his love of vintage recording equipment, and his extensive knowledge and collection of classic valve amps, effects and pedals”. He's also got several Pro Tools H3 rigs loaded to the brim with plug‑ins. Monitoring is provided by KRK 9000B and Yamaha NS10 nearfields with Bryston amplifiers, but also by a Pure portable digital radio.

"I like the SSL for many reasons. I like the general sound of it, I like the EQ, and I like the sound it creates when it busses everything together. I also have an SSL Duality in the prep and post‑production room upstairs, which is fantastic — a very interesting step forward from the very large consoles to something more manageable. I'm in discussions with SSL on how to improve that desk. For now I'm still using the G‑series, which is my favourite SSL, and which obviously also functions as an interface for all my outboard. Concerning monitoring, I'm without a doubt strongly influenced in my choice by Spike. I used KRK E8s for a while, but the reliability wasn't good, and since I've put the 9000s up again, there's no going back. I tend to mix very quietly on smaller speakers, and I use my Pure Evoke 3 portable digital radio a lot, which works very well for editing and balancing. I've also recently been listening to Focal Twins, which are very good. I can easily switch between 15 different speakers. I couldn't just mix on NS10s or KRK 9000s; it would be too tiring and you get used to them too much.

"With regard to outboard, I began my career in the late '80s, and while I could have been totally into digital, my first engineering experiences were on old vintage Neve desks and things, and I also had great experiences with guitar pedals, which I love to this day. I still find analogue more pleasing to the ear. I use digital for a number of things, but I just love analogue. With regard to plug‑ins versus outboard, I don't think there's a contest. They are two different things doing different jobs. It's fantastic that I have the opportunity to use each for what it's good at. There are some Waves EQs that are amazing, and that can be far more surgical than analogue equalisers for removing frequencies that are getting in the way in a mix. For instance, when mixing Snow Patrol, I may have 12 of the same guitars that all have the same ringing frequencies, and I'd never be able to get rid of them using analogue EQs.