SpectraLayers One is a powerful vocal unmixing tool for Cubase 11 Pro and Artist users.

SpectraLayers One is a powerful vocal unmixing tool for Cubase 11 Pro and Artist users.

SpectraLayers One allows you to tweak vocals that are ‘baked into’ a stereo mix!

Have you ever wished, when you don’t have access to the original multitracks, that you could have the ability to ‘unmix’ the different elements within a stereo file to gain access to individual parts — particularly the lead vocals?

Until recently this was rather like attempting to unbake a cake to access the eggs and flour, but the latest generation of spectral‑editing software makes it more viable and one such app, SpectraLayers One (from here SL One), is bundled with Cubase 11 Pro and Artist. SL One may be a cut‑down version of the separately available SpectraLayers Pro 7, but it does boast one of its bigger sibling’s eye‑catching features: stem unmixing. It can only create two stems (vocals and ‘everything else’), but that’s just what you need if you want to do some post‑mix vocal tweaking! In this workshop, I’ll explain what you can do with it, and you’ll find some accompanying audio examples on the SOS website (https://sosm.ag/cubase-0821). Alternatively, download the ZIP file of audio examples here:

You’re The One

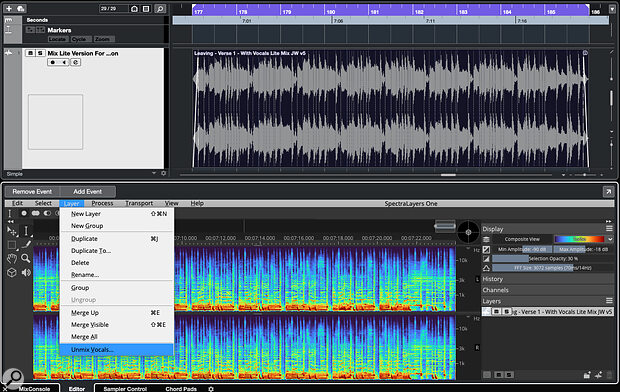

SL One can run as a standalone app or as an Audio Extension on a Cubase audio clip within. The first screen shows the letter, which allows you to combine SL One processing with further processing and effects in Cubase. Once the Extension is applied, SP One and its various tools appear in Cubase’s Lower Zone.

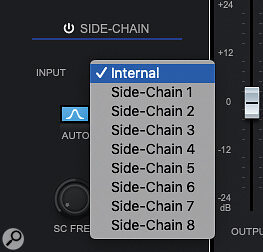

The unmixing process requires almost no user intervention and is very fast!For our purposes, we require the Layer/Unmix Vocals option and, despite the under‑the‑hood complexity, it couldn’t be simpler to use: the only user‑defined control is the Sensitivity slider setting. The default ‘zero’ setting has generally provided the best results for me, but I’ve included an audio example (link above) to demonstrate the differences. Essentially, positive Sensitivity values put more audio into the vocal stem but may include more fragments of other mix elements too, while negative Sensitivity settings are less likely to place other instruments in the vocal stem but can leave more vocal trace elements in the ‘everything else’ stem. Depending on what you’re trying to achieve, either could be useful.

The unmixing process requires almost no user intervention and is very fast!For our purposes, we require the Layer/Unmix Vocals option and, despite the under‑the‑hood complexity, it couldn’t be simpler to use: the only user‑defined control is the Sensitivity slider setting. The default ‘zero’ setting has generally provided the best results for me, but I’ve included an audio example (link above) to demonstrate the differences. Essentially, positive Sensitivity values put more audio into the vocal stem but may include more fragments of other mix elements too, while negative Sensitivity settings are less likely to place other instruments in the vocal stem but can leave more vocal trace elements in the ‘everything else’ stem. Depending on what you’re trying to achieve, either could be useful.

Once the processing is complete, it can take a minute depending on the length of the audio clip. The two stems appear in SL One’s right‑hand panel, with mute and solo buttons that allow easy auditioning of the results. This unmixing process is non‑destructive: if you play back both stems together without further processing, they’ll sum to deliver the original mix. Auditioned in isolation, the vocal stem will inevitably show some artefacts (unless you started with a particularly sparse mix, with few other sounds overlapping the vocal). These artefacts may be non‑vocal elements (eg. traces of drums) or ‘missing’ vocal information that remains in the ‘everything else’ stem. You can hear elements of both types of artefact in the accompanying audio examples.

Whether you consider the vocal separation successful will depend on just what you hope to achieve. But given that vocal extraction/isolation is often a last resort, because the original mix project is unavailable, ‘usable’ can almost always be considered a positive outcome — so, are these sorts of results usable?

Balancing Act

Using these two unmixed stems to modify the level of the vocal relative to the instrumental backing is likely to be the easiest trick to pull off. For example, if we wished to raise the vocal level by a dB or three, we can do this by adjusting the gain of the vocal stem. While that will also adjust the level of any artefacts in the vocal stem, they are often difficult to detect in the context of the ‘reassembled’ mix.

Once separated, the stems created can be dragged and dropped to the Cubase project window for further processing or editing.

Once separated, the stems created can be dragged and dropped to the Cubase project window for further processing or editing.

When used in stand‑alone mode, SL One includes gain sliders for the two stems and these are not available when using the ARA2 plug‑in in Cubase. Instead, you can drag/drop each stem to a new Audio Track in your Cubase project. Not only does this allow you to rebalance them, but you can then apply further editing, audio processing, or automation to the individual stems, to improve the blend of your ‘rebalance’.

In my second audio example, gain changes ranging from ‑3 to +6 dB are applied to the vocal stem. Your mileage may vary, but to my ears all these rebalanced versions seem pretty effective and transparent. Rebalancing isn’t all that can be done though; as a final stage in this audio example, I’ve added a fresh dollop of both reverb and delay, just to show that more creative changes are also possible (so feel free to experiment!).

A second potential application of SL One’s unmixing facility is to silence the vocalist, to create a backing track. Such a vocal‑free backing track might be used, for example, for personal practice for a vocalist, as a karaoke track, or to generate an underscore music cue for film/TV use where the vocals might impinge upon dialogue. I’ll leave you to navigate any copyright implications, but as the third audio example demonstrates, SL One can take a good stab at this with minimum effort on the part of the user.

As the isolated vocal stem has revealed, the separation process is not perfect but, as a means of recusing an instrumental version from a full mix, the default results may well be acceptable in some contexts and a little additional editing can easily improve things further.

Ready (Re)Mix?

The Holy Grail of this unmixing process would be a perfectly isolated vocal track but unless your starting point is a very sparse mix, that’s an incredibly ‘big ask’. Yet, if your isolated vocal stem is intended for use in a remix or mashup project, in which it will be layered with a suitably busy backing track, then might SL One be up to the task?

The fourth example explores just how realistic this proposition might be...

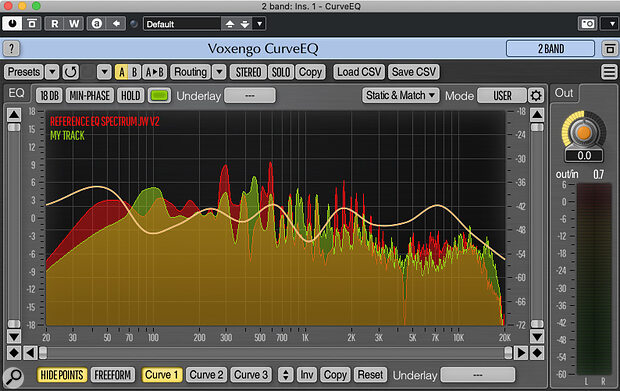

SpectraLayers Pro can generate up to five stems from a stereo mix and, when used in standalone mode, both One and Pro offer gain controls for easy rebalancing of your stems.

SpectraLayers Pro can generate up to five stems from a stereo mix and, when used in standalone mode, both One and Pro offer gain controls for easy rebalancing of your stems.

I’ve taken the default unmixed vocal stem from our earlier short ‘verse’ audio mix (artefacts included) and built a new backing track for this extracted vocal. In the audio example, I’ve gradually added layers of instrumentation with each pass through the performance. Layered with a single instrument such as a strummed guitar or solo piano, the artefacts are audible — this might still be useful as a scratch vocal to build a ‘vocal + guitar’ or ‘vocal + piano’ remix project, but it’s unlikely to cut the mustard in a release context without considerably more detailed editing work or a new vocal recording. Note, though, that many of the artefacts in the vocal stem appear to be drum related and once new drums and bass are added to a remix, the majority of them are masked.

At this point, it’s not such a stretch to think that even some modest spectral editing on the vocal stem might generate a very usable vocal part, and as more layers are added to the instrumental bed (the final few passes in the audio example include multiple guitars and a synth) the artefacts become even less obvious. So if your remix has a prominent drum beat and doesn’t leave the extracted vocal too exposed, SL One’s vocal unmixing may well prove very usable.

Density Matters

As noted earlier, the success of this vocal unmixing process is very much dependent on the original mix. The one I’ve used for the audio examples is what I’d call moderately dense, and SL One has done a commendable job. But what if your source mix is busier?

As a final audio example, I’ve used an alternative version of my short ‘verse’ clip that contained additional instruments (an extra guitar, a keyboard part and some harmony vocals). It’s no surprise that the resulting vocal stem has more artefacts. But, even if it would be more difficult to use the isolated vocal stem in a remix context, the vocal rebalancing and backing track creation discussed above remain distinctly possible.

SL One doesn’t handle the obvious legal obligations of publishing works using stems extracted from commercial recordings, but it does make the technical side of the ‘unmixing’ process remarkably easy and efficient. And, of course, it’s a freebie for Cubase 11 Pro and Artist users. Whether it’s vocal rebalancing, backing track creation or, with a bit of luck, vocal isolation, Cubase 11’s SL One can make something that used to be difficult into something remarkably easy.