The Pattern Editor makes a great starting point for generating arpeggio‑style patterns.

The Pattern Editor makes a great starting point for generating arpeggio‑style patterns.

Need a better arpeggiator? Cubase’s Pattern Editor can deliver the goods!

The new Drum Machine and Pattern Editor features in Pro and Artist versions of Cubase 14 are obviously designed to complement each other. However, the Pattern Editor feature set also provides some interesting possibilities for designing synth arpeggio patterns. So, if you are fond of the occasional arp, pick yourself a pluck sound, pluck up your courage, and let’s see what I’m ’arping on about...

Making Notes

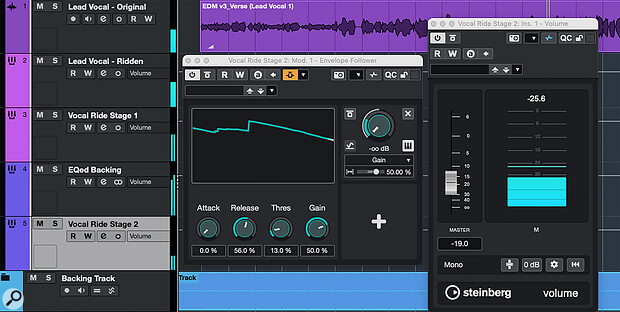

Cubase has long had a number of tools for creating arpeggio patterns, including the Arpache MIDI plug‑ins and the arpeggio engine built into Retrologue. However, the Pattern Editor provides a very neat alternative because it offers some creative options. For this example (for which I’ve created accompanying audio examples on the SOS website: https://sosm.ag/cubase-0525), I’ll use an instance of Retrologue with a short ‘pluck’ style synth preset. The first step, though, is in the Add Track dialogue box: select the Pattern Editor option as the Event Type. When you then select this new track in the Project window (as shown in the first screenshot), the Editor tab in the Lower Zone will show you the Pattern Editor rather than the standard MIDI Editor.

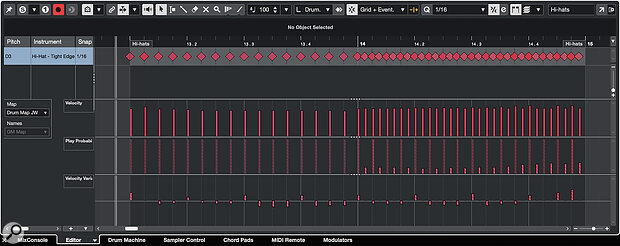

When used with Drum Machine, the Pattern Editor automatically configures lanes for each of the available drum sounds linked to the correct MIDI note. That’s great for obvious reasons, but for a melodic instrument you’ll need to reconfigure this — to make pattern creation easier it makes good sense to set up lanes only for any notes that you know you’ll need. For example, in the screenshot, I’ve just set up lanes for a single octave (C3 to C4), using only notes in the C major scale. You could pick more exotic key/scale/note combinations if you wish, and use a span of notes over multiple octaves too; the choice is yours, depending on how complex you like your arpeggio patterns to get. Also, observe that I’ve assigned the notes in pitch order (lowest pitch at the bottom of the lane list). This isn’t how the Pattern Editor would do things by default, and I don’t think you can simply drag/drop lanes to reorder them — plan ahead, and you won’t have to do this twice!

Built By Hand

To keep things simple for this demonstration, I opted for a conventional 16‑step, 16th‑note grid on which to build my arpeggios, but you can adjust these settings globally (in the Pattern Editor’s topmost menu bar) or on a per‑lane basis (although, there are some quirks to how lanes with different step counts behave if more unusual rhythmic patterns are your thing).

Once dropped onto the timeline, you can easily change the pattern number or convert the patterns into standard MIDI parts.Creating your first pattern manually (by clicking on step combinations when playback is active) lets you quickly experiment with the basic structure of your arpeggio’s starting point. And although we’re using it as an arpeggiator, note that this is really a step sequencer, and that means you can add multiple notes on an individual step if you want to trigger a chord here or there as well as a melodic line.

Once dropped onto the timeline, you can easily change the pattern number or convert the patterns into standard MIDI parts.Creating your first pattern manually (by clicking on step combinations when playback is active) lets you quickly experiment with the basic structure of your arpeggio’s starting point. And although we’re using it as an arpeggiator, note that this is really a step sequencer, and that means you can add multiple notes on an individual step if you want to trigger a chord here or there as well as a melodic line.

Once you have an initial pattern (named Pattern 1 by default), hit the Duplicate button in the toolbar. This will preserve your original pattern should you need to go back, while also creating a copy (named... yup, Pattern 2) that you can begin to get a little more creative with. Patterns can be renamed, of course, and that can make it easier to keep track of multiple versions of your arpeggio as you work.

Variations On A Theme

The Pattern Editor is a super‑simple environment for hand‑crafting an arpeggio, but it really comes into its own for adding musical interest by generating variations. This is possible because of the various randomisation, probability and modulation elements in the Pattern Editor’s features set. Randomisation options are available both globally (in the toolbar) or on a per‑lane basis.

For our use case, the most appropriate options are available in the Parameter Lanes, located at the base of the Pattern Editor panel. These operate on a per‑lane/per‑step basis and allow you to set, for example, per‑step velocity for the notes in your arpeggio pattern. However, providing your synth sound is velocity sensitive, you can also add Velocity Variance and playback Probability (as in the main screenshot) to any active notes in the currently selected lane. And, as both of these elements (Velocity Variance and Probability) add their randomisation on each pass through the pattern, you can introduce some performance variation on playback. Subtlety generally works best here, but feel free to experiment.

These randomisation options work best if you avoid notes that hold the core of the pattern (such as the whole‑beat steps), because when these go ‘missing’ the rhythmic sense of the arpeggio can get lost. Applied to notes towards the end of the bar, though, such as steps 13 to 16 in our 16‑step example, they can work really well to add melodic interest/variation.

Three further things are worth noting here. First, you can add step‑based modulation of your synth’s parameters in the Parameter Lane section. Simply tap the ‘+’ icon and you can select a target parameter to add to the existing selection. Second, if you want to reset the values in any parameter lane to their original starting points, hold the Ctrl/Cmd button while clicking (or dragging) in the lane. Third, to start with at least, just build your initial patterns starting on the same root note. We’ll get on to adapting them to the chord sequence in your project shortly.

Arp Arranger

Once you have created a few pattern variations, the next step is to arrange them on your project timeline. This aspect of the Pattern Editor’s design is rather neat: you can drag and drop patterns to your track using the button next to the pattern name box. Whichever pattern you currently have selected is placed on the timeline. Like a MIDI clip, you can then drag the middle‑right handle of the dropped pattern to repeat it (for example, to create four bars of Pattern 1). You can, therefore, easily lay out your various patterns into a longer sequence. Each pattern shows its pattern number top‑right, and clicking on this opens a drop‑down menu — great if you need to change the pattern number for a particular instance. This can be seen in the topmost track of the first screen.

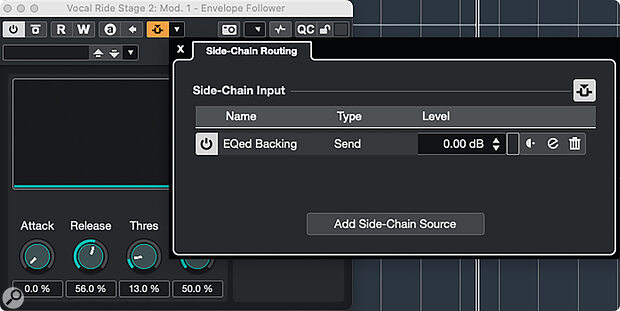

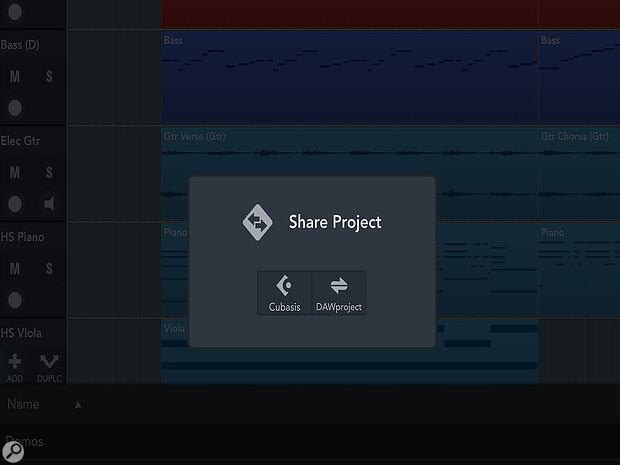

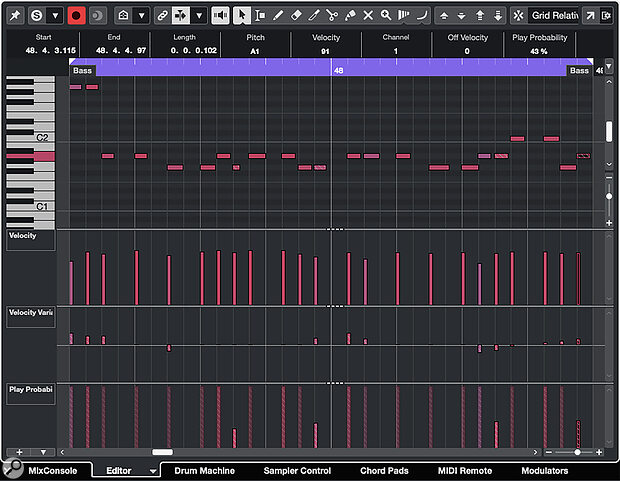

With your sequence of patterns in place, you can get those patterns to adapt to the chords used in your project. There are a number of ways to approach this, but (as in the screenshot) the simplest is to use Chord events placed on the Chord Track. In this first Pattern Editor iteration, pattern events don’t automatically follow the Chord Track, but if you select all the required pattern events and open the pattern number selection drop‑down menu again, you can choose Convert Pattern Event to MIDI Part. This does exactly what it says on the tin: it generates a standard MIDI clip. But, rather wonderfully, these ‘rendered’ MIDI clips still include the randomisation and probability variations we configured in the Pattern Editor.

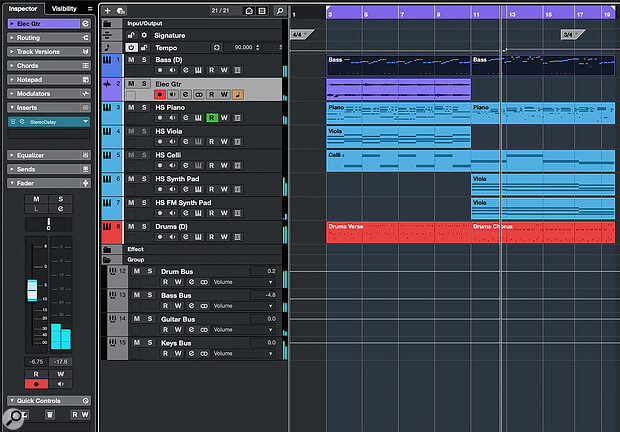

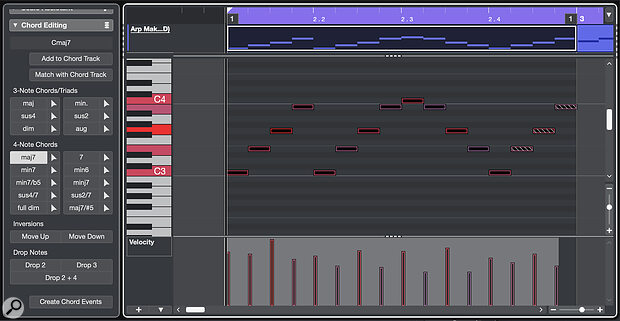

Once your pattern‑based MIDI is following the Chord Track, the Chord Editing panel provides additional options for voicing of the chord notes.

Once your pattern‑based MIDI is following the Chord Track, the Chord Editing panel provides additional options for voicing of the chord notes.

If you add a Chord Track, you can sequence your project’s chord changes using Chord Events placed on that track in the usual way. With that done, in the Chords panel in the Inspector you simply set your newly converted Pattern Editor MIDI track to Follow Chord Track. There are a number of configuration options here, but the most basic Chords & Scale or Chords options should be fine as a starting point. The notes in your various patterns will then be adjusted to match the chord changes in the Chord Track. The second track in the main screenshot has been treated in this way.

This may well be all you need, but if you want to add a little extra interest then, as on the third track in the first screenshot, simply select one of the MIDI clips and, in the MIDI Editor, select the notes in that clip. You can then dip into the Chord Editing panel and start experimenting. You can actually change the chords themselves here, but simple options such as the Inversions and Drop Notes buttons can be very effective — these make it easy to voice the notes in a specific chord in different ways, including over more than a single octave.

Finally, the advantage of using the Chord Track as part of this process is that you can get multiple Pattern Editor‑inspired tracks to synchronise to the same chord changes. This is exactly what I’ve done with both an arpeggio synth and bass synth in the last of the audio examples that you can audition on the SOS website.

More Mods?

Finally, we mustn’t forget that Cubase’s new Pattern Editor is great for its primary design intention — inspiring new drum beats. But as I’ve hopefully demonstrated above, it’s also brimming with unplanned creative potential, so I’m now crossing my fingers and hoping that Steinberg continue to evolve the possibilities it offers. For example, both a pattern preset system and the option for patterns to follow the Chord Track would be great (though I’ve no idea of the technicalities of making this latter option work!). Meanwhile, playtime with patterns can be a lot of fun. Enjoy!