Published 3/7/19

24-key modular controller keyboard appeals to both keyboard beginners and pros

ROLI have been impressing us with innovative controller designs since the launch of their otherworldly Seaboard Grand four years ago (see the review in SOS September 2015). Their latest product offers all the depth and innovation of their previous products, but channelled in a very different direction. As its name suggests, it's all about light.

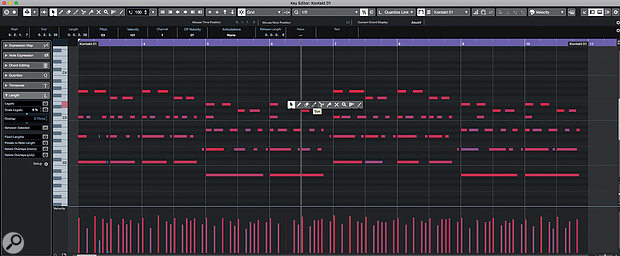

Like ROLI's earliest products, LUMI is a controller based around a keyboard-like interface, but the loose resemblence ends as soon as you power it up, because in stark contrast to the monochromatic Seaboards, LUMI comes alive in a riot of colour. Each of its 24 keys is lit evenly along its entire length from underneath by super-bright variable LEDs — so each one can be a completely different colour.

This simple idea is used to excellent effect to assist a major part of LUMI's target market: those of any age who are learning to play the keyboard. Thus it ships with a proprietary iOS or Android music training app with a library of songs, and if you select one, the keys will light up brightly in sequence, allowing keyboard learners to follow and play the melody (and accompanying chords, if you wish) for the selected song by following the lights. While there have been educational keyboards with 'followable' LED strips or lights above the keys before, we can't call to mind any on which the entire key can light up so brightly and in such a wide range of colours before — and the intuitive impact of being able to follow the lights as an aid to playing is not to be understated. For songs already in the LUMI app's library, there is a wealth of extra content to help you master playing, from videos showing you optimum fingering to performance training routines, where you accompany a scrolling score on the app, a piano-roll display, or simply follow LUMI's lights, and the app rates your accuracy and speed.

The library will cover music from classical to cutting-edge; at the demo we attended, it was still under development, but already contained works from Bach to the Beatles, Sia and Calvin Harris. However, the app will not be limited to audio material already loaded in its library — in time, the plan is that it will be able to analyse the music in any audio file presented to it and swiftly provide a light-up key sequence for the melody, and a best guess at the key and chords too. We saw an early demo of this aspect of the app in action: we were asked to freely pick a well-known track completely at random. Slightly mischievously, we chose one not in the LUMI library — The Beatles' 'Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds', well known for its various key changes — and watched as the app not only identified the keyboard and vocal melodies from a quick playback on Spotify, but also tracked the key changes through the verse into the chorus and back again. Once this feature is fully working, it could in theory allow fledgeling keyboard players to learn whatever songs they like quickly and easily.

If your initial impression is that you have no need for this kind of educational aspect to a controller, and the 24-note span and light-up keys call to mind countless cheap plastic kids' keyboards or even the atonal early 80s warblings of Hasbro's circular toy Simon, think again. LUMI is a fully specified, modular and highly portable self-powered MIDI controller, with polyphonic aftertouch. In the studio, it integrates smoothly with DAWs and ROLI's own Studio Player and Dashboard software, and also physically with other hardware; each LUMI 'unit' features ROLI's proprietary magnetic 'DNA' connectors along its edges, as used on their innovative Blocks control hardware, so ROLI's control Blocks, Lightpads or Seaboards can be instantly attached if required. What's more, if you want or need a larger keyboard, you simply snap LUMI keyboards seamlessly together (up to maximum of four).

The keyboard itself and its action have been carefully designed for playability by pros as well as beginners, with a 'plunge' almost as deep as that of a grand piano and keys corresponding to the Donison Steinbuhler 5.5 standard, seven-eighths of the width of a standard piano keyboard (for those unfamiliar with DS5.5 keyboards, their dimensions are widely believed amongst music educators to be more approachable and playable than standard-sized piano keys). Measuring 282x141mm, only 27mm thick, weighing 600g per 'unit' and with an approximate battery-powered life of six hours when fully charged, LUMI also fits into a rucksack for easy use outside the studio. How many other controller keyboards are portable and modular, allowing you to assemble a backpackable 96-key 'Imperial' controller?

Even if the educational aspects of LUMI's light-up design are unimportant to you, there are many possible pro applications for the coloured keys in a live or performance context. Because the colour of each key is individually customisable in ROLI's Dashboard software, you could colour keys depending on the samples assigned to each key during live performances as an unforgettable aide-memoire, or colour different zones of the keyboard to highlight split points... or, yes, if you like, draw attention by giving your keyboard a completely different colour scheme for every song in your set, simply because you can. It's surely only a matter of time before LUMI is a major visual component in someone's super-hip video...

Reflecting the new keyboard's broader appeal to learners and non-technical musicians as well as the pro musicians that have formed most of ROLI's customer base since their launch, LUMI is initially being sold using a crowdfunding model, via Kickstarter, rather than through pro-audio distribution channels or via the main company site. At the time of writing, a few days after its launch, LUMI has over 5000 backers and has exceeded by more than tenfold its initial funding goal of £100,000, which suggests this model was a shrewd approach! It's expected to be on sale from October (with one eye on the Christmas stocking market, perhaps?) and will retail then for $249 in the USA, although as of the start of July, it's still possible to secure LUMI for under $200 by signing up as a backer on Kickstarter. See the link below for details.

by (SOS) 2019