A limiter's primary function is to prevent the loudest signal peaks from exceeding a specified maximum level, but they're often also used as a 'maximiser' to increase loudness — as you raise the input signal, everything below the limiter's peak detection threshold gets louder, while the peaks are reduced to the threshold level. But the latter tactic can mean the limiter both acting more frequently and applying more attenuation, and the more you ask your limiter to do, the more unwanted sonic artifacts it will leave behind. Eventually, it will become audibly unpleasant.

The Brickwall Limiter inserted on a drum bus Group Track, with the track's Pre Gain control used to adjust the input gain.You can't simply crank up the gain and hope for the best, then; you must train yourself to hear exactly how the limiter is changing your audio. When you overdo it significantly, it's very easy to hear any damage being done. But, especially when you first start experimenting with limiters, it can be harder to judge where the sweet spot is.

The Brickwall Limiter inserted on a drum bus Group Track, with the track's Pre Gain control used to adjust the input gain.You can't simply crank up the gain and hope for the best, then; you must train yourself to hear exactly how the limiter is changing your audio. When you overdo it significantly, it's very easy to hear any damage being done. But, especially when you first start experimenting with limiters, it can be harder to judge where the sweet spot is.

To make this a little easier, you can use a technique that's often referred to as 'delta monitoring'. Essentially, this requires you to subtract the processed signal from the unprocessed one, so that you can listen to the remainder, which is what your limiter is removing. Some third-party plug‑ins helpfully include delta monitoring facilities (Tokyo Dawn Labs' Kotelnikov and Limiter 6, for example), but a little creative audio routing allows you to achieve it with almost any plug‑in in Cubase (or, indeed, any other DAW). I've used Cubase's simple Brickwall Limiter for the examples that follow.

Hitting Bricks

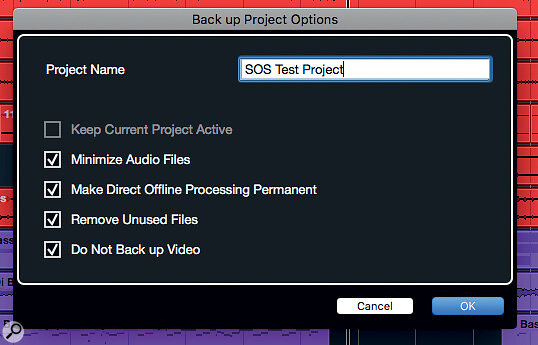

You can start by familiarising yourself with the Brickwall Limiter by using it on a drum bus track, as per the first screenshot — I've used the Gain control in the MixConsole's Pre section to set the signal level coming into the Brickwall Limiter. This plug‑in offers switchable dual-mono or stereo operation (via the Link button; best left engaged unless you have specific reasons to change it) and an auto-release option that generally works well. The most important control, though, is the Threshold slider, which sets the maximum level a signal can reach before limiting is applied. Any peak that exceeds this level is quickly brought down to the threshold.

To reduce the possibility of exceeding 0dBFS, you should set the Threshold to allow a small margin of error — the screenshot example shows 2dB of headroom left on a drum bus limiter. But if in doubt, the DIC (Detect Intersample Clipping) feature adds an extra level of safety; it uses a lookahead oversampling process that, at the cost of an additional 1ms of latency, ensures the signal won't exceed the Threshold, even at a point between two samples.

Take It Away

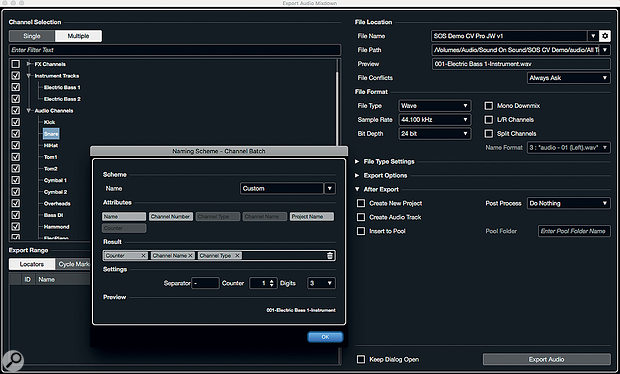

Delta monitoring: the final track and routing configuration required to isolate the audio differences between the processed and unprocessed versions of the drum bus signal.Now let's look at how we can set up delta monitoring to better hear what this limiter is doing — the final configuration is set out in the second screen, but a number of steps are required to get there. I'll assume we're starting with a limiter on the drum bus, as described above.

Delta monitoring: the final track and routing configuration required to isolate the audio differences between the processed and unprocessed versions of the drum bus signal.Now let's look at how we can set up delta monitoring to better hear what this limiter is doing — the final configuration is set out in the second screen, but a number of steps are required to get there. I'll assume we're starting with a limiter on the drum bus, as described above.

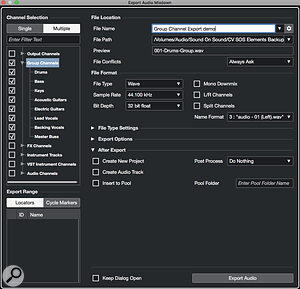

First, create two FX Tracks and insert an active (ie. not bypassed) instance of the Brickwall Limiter on each. Initially, configure these two instances identically to the one on your drum bus. Then disable the drum bus track's output (in the Routing section), and create two sends, each at unity gain (0dB), each going to a different one of your new FX Tracks. The audio from the drum bus now flows to the master output only via these two FX Tracks, so you can bypass the Brickwall Limiter on the drum bus track. Don't engage playback just yet, though, or the signal will be twice as loud as the original!

Now, in the Pre panel of the second FX Track, switch the 'phase' (polarity) from 0 to 180 degrees. Engage playback now, and you should hear silence — the two FX Tracks are playing identical audio out of phase and therefore perfectly cancel. Finally, bypass the Brickwall Limiter on the second FX Track. Now, identical parts of the audio will still cancel, but where the limiter has acted you'll hear only what it has removed.

Split The Difference

That was easy enough, but what does it tell you? Well, for a quick example (because it results in an obvious difference), experiment with the Threshold setting and listen to how the characteristics of the delta signal change. In practice, though, the Threshold is likely to be a 'set and forget' parameter. It's more interesting to change the input level (in this case, via the Gain control within the drum bus track's Pre section).

As you'd expect, as you increase the gain, you force the Brickwall Limiter to work harder, and the differences between the processed and unprocessed audio become increasingly obvious. These differences manifest themselves in three ways. First, you can hear which elements within your audio are being altered most by the limiting (whether on a drum bus or a full mix, this will probably be the kick and snare drums). Second, you may be able to hear some audio nasties, which may encourage you to think about just how far you should push your limiter. Third, the delta monitoring signal will include any gain differences that are introduced by the processor itself.

In my example, the gain change is applied equally to both FX Tracks because it's performed on the drum bus Group Track that feeds them — so you won't hear any gain differences. But if the plug‑in being monitored is one with an input gain control (Cubase's Limiter, for example), and you adjust this in the FX Track instance of the plug‑in, then the delta signal will include this gain difference, and it will be present whether or not the limiter's gain reduction circuit is active. (It's also a great way to spot plug‑in presets that try to trick your ears with a sneaky 'louder-sounds-better' boost!) There are pros and cons to both approaches: it can be handy to hear just the limiting, or a combination of the limiting and any gain change.

Listen & Learn

Of course, while I've used limiting for this example, the same approach can work with almost any plug‑in. For example, try it with a compressor, or tape saturation processor if you struggle to hear precisely what it is they're doing. As a means of educating your ears, it's a really helpful technique. Hearing the differences isolated in this way can be really interesting, and when you then go back to monitoring the processed signal in the normal way, you'll hopefully have a better idea of just what artifacts to listen out for as you adjust the plug‑in's controls.

Audio Examples

I've created a number of audio examples so that you can hear what I'm writing about. You'll find them on this accompanying page:

www.soundonsound.com/techniques/cubase-delta-monitoring-audio-examples

Stream them by all means, but as this is about critical listening, you'll have a much better experience if you download the Zip file of uncompressed WAV versions and audition them in your DAW.