The Channel Settings window provides a flexible and efficient environment for many basic mix processing tasks.

The Channel Settings window provides a flexible and efficient environment for many basic mix processing tasks.

Could Cubase 10's Channel Settings window become your go-to mixing tool?

Cubase's Channel Strip has the potential to make mixing much more efficient. Indeed, the same concept has translated fairly well from its hardware origins into most modern DAWs now. But when screen space is at a premium some implementations can require considerable screen real-estate — and while the collapsible Rack system in Cubase's MixConsole is brilliant in so many respects, accessing all the controls for each channel can entail a lot of opening/closing of Racks or scrolling up/down.

A small-screen-friendly alternative is to build your workflow around the Channel Settings window. Sure, you can only display controls for one channel at once, but this window makes the complete Channel Strip's controls available in a very easy-to-use format. And with the useful refinements Steinberg made to the operation of the Channel Settings window in Cubase 10, you really should consider putting it at the heart of your mixing workflow.

Channel Guide

The Channel Settings window can be opened for the currently selected track/channel by clicking on the 'e' button in the Project window's Track List or in the MixConsole, and it gives you access to the full control set that's found in the MixConsole — but in a larger, easier to use GUI.

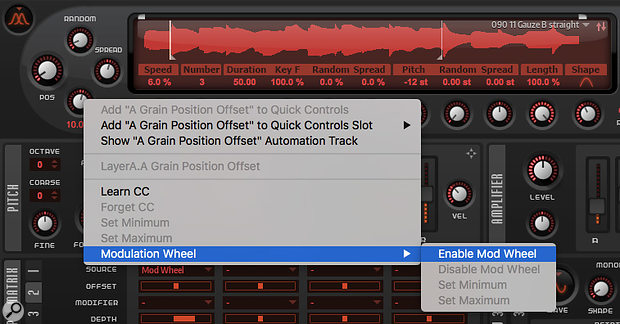

As in previous versions, the contents of the MixConsole's EQ and Channel Strip Racks dominate the central portion of the display, but in v10 Steinberg made some worthwhile tweaks to what's possible here. For example, the UI was improved to offer better access to the core controls of each module, the visual feedback/metering was revamped and, while the EQ section could already be viewed in an expanded form via the Equalizer tab, you can now do that for the Compression section too (via a further 'e' button). The Channel Strip tab now includes a compact version of the EQ section in situ, and you can drag and drop to change the order of the various modules in the signal flow, which makes it much easier to see and configure your preferred processing chain.

The Sound Of Beating Drums

When considering what the Channel Settings approach might offer you, there are two key questions to ask. First, are the tools provided up to the job? Second, how can they facilitate a more efficient workflow? The first is a huge question, but by way of example let's briefly consider a common mixing task: submixing a multitrack drum recording. In the example shown in the first screen there are seven mic channels, with single kick, snare and hi-hat mics joined by pairs of overheads and room (ambience) mics. For all the shiny appeal of your third-party plug-ins, the stock Cubase plug-ins in the Channel Strip and EQ sections are more than capable enough for routine mix-processing tasks like this, so the bulk of your work can easily be done in the expanded Channel Strip display.

The exact settings required for each module across the various drum channels will obviously be project-specific, but it's worth exploring some cool features in the Channel Strip plug-ins. For example, the Noise Gate features a very useful input filter, and you can activate this via the AF button. You can then engage the LST (listen) function while you adjust the Freq and Q settings of the filter to focus the action of the gate within the dominant frequency of each sound source. In this drum mix, I used this on the kick, snare and hi-hat mics, and it allowed me to maximise the spill rejection from other drums into those mics.

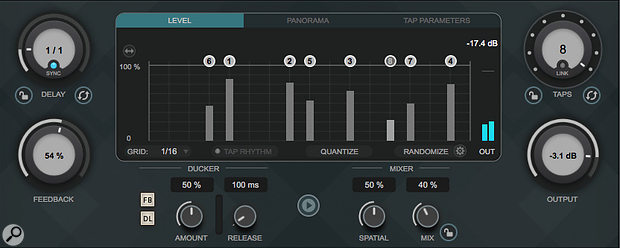

You can now access the full control set for your selected compressor within the Channel Settings window.It's also worth noting that all three compressor options (Standard, Tube or Vintage), which offer different characters of compression, also include Mix controls — making it possible to experiment with parallel compression on individual drum mics without leaving this window. And that, alongside the expected four-band EQ controls and an expanded display of the EQ curve, the Equalizer tab grants you access to controls from the MixConsole's Pre section. Most usefully, this includes a variable-slope low-cut filter for routine high-pass processing, and the Phase button (a polarity inverter), which is useful to optimise the phase relationships of multiple mics used on a single source. In this drum mix I used the low-cut filter to remove unwanted rumble to varying degrees on all the tracks (yes, even the kick), and set it higher for the two room mics, to prevent the kick being too ambient.

You can now access the full control set for your selected compressor within the Channel Settings window.It's also worth noting that all three compressor options (Standard, Tube or Vintage), which offer different characters of compression, also include Mix controls — making it possible to experiment with parallel compression on individual drum mics without leaving this window. And that, alongside the expected four-band EQ controls and an expanded display of the EQ curve, the Equalizer tab grants you access to controls from the MixConsole's Pre section. Most usefully, this includes a variable-slope low-cut filter for routine high-pass processing, and the Phase button (a polarity inverter), which is useful to optimise the phase relationships of multiple mics used on a single source. In this drum mix I used the low-cut filter to remove unwanted rumble to varying degrees on all the tracks (yes, even the kick), and set it higher for the two room mics, to prevent the kick being too ambient.

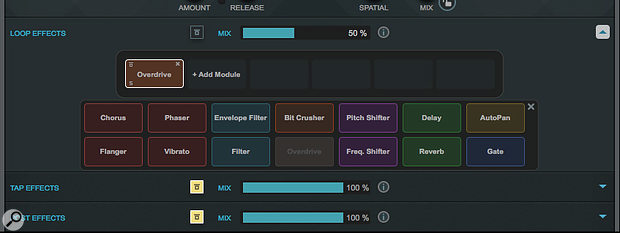

The EQ tab includes full access to the four-band EQ but also the very useful high-cut and low-cut filters from the Pre Rack section.The Tools section offers a choice of the DeEsser (useful for vocal tracks, obviously, but drums too on occasion) and EnvelopeShaper. The latter is very useful for drums and a doddle to use. In this mix I use it to enhance the attack of the kick and snare, to help them punch through more clearly. Finally, I applied a subtle amount of saturation to all the channels (you can choose between Magneto II, Tape or Tube options) and limiting (Standard Limiter, Brickwall or Maximizer) just to control any really hot peaks.

The EQ tab includes full access to the four-band EQ but also the very useful high-cut and low-cut filters from the Pre Rack section.The Tools section offers a choice of the DeEsser (useful for vocal tracks, obviously, but drums too on occasion) and EnvelopeShaper. The latter is very useful for drums and a doddle to use. In this mix I use it to enhance the attack of the kick and snare, to help them punch through more clearly. Finally, I applied a subtle amount of saturation to all the channels (you can choose between Magneto II, Tape or Tube options) and limiting (Standard Limiter, Brickwall or Maximizer) just to control any really hot peaks.

I've provided a couple of audio examples, in which I compare my raw drum tracks to the drum 'mix', with processing configured solely in the Channel Settings window on each track. To my ears, the end result is clearer and has more punch — I achieved what I set out to achieve using only these tools. So whether or not you have access to third-party, channel strip-style plug-ins, I'd say the Cubase Channel Settings toolset could take you a long way along your mixing journey. For routine mix tasks, at least, I'd answer our first question with an emphatic 'yes'.

Command & Conquer

What about ease of use? Well, like the channel strips on a hardware console, a good dollop of that ease of use comes from the consistency of the control set for every channel. As you build up experience with the common control set, your familiarity will translate to much faster operation. But the other element that contributes to workflow efficiency is how quickly you can navigate the controls within the Channel Settings window itself. If you're fortunate enough to own Steinberg's CC121 hardware controller, that navigation will be very slick. But even for the rest of us, there are options and shortcuts that can speed things up.

As a starting point, for frequent use, I'd define a keyboard shortcut for the Edit Channel Settings option (you can create/edit shortcuts in the Edit section of the Key Commands dialogue) so you can quickly open and close the Channel Settings window; I've assigned the 'E' key to this, as it matches the on-screen button.

To get the most from the Channel Settings window, defining a few key commands will greatly enhance the workflow, including the ability to swiftly move between different tracks and channels.For the fastest workflow, two further options are worth enabling, and both are accessible from the pop-up menus in the top-right of the Channel Settings window. First, from the Toolbar menu, enable 'Always On Top'. This prevents the Channel Settings window from disappearing behind other windows as you work (once open, it's always accessible). Second, from the Function menu, enable 'Follow 'e' buttons or selection changes', so that when you select a different track/channel in the Project window or MixConsole, the Channel Settings window will update to display the newly selected track/channel's settings.

To get the most from the Channel Settings window, defining a few key commands will greatly enhance the workflow, including the ability to swiftly move between different tracks and channels.For the fastest workflow, two further options are worth enabling, and both are accessible from the pop-up menus in the top-right of the Channel Settings window. First, from the Toolbar menu, enable 'Always On Top'. This prevents the Channel Settings window from disappearing behind other windows as you work (once open, it's always accessible). Second, from the Function menu, enable 'Follow 'e' buttons or selection changes', so that when you select a different track/channel in the Project window or MixConsole, the Channel Settings window will update to display the newly selected track/channel's settings.

Given that the Channel Settings window only displays settings for the currently selected channel/track, the other thing we must be able to do is move efficiently between tracks. There are buttons for this in the Channel Settings window itself but key commands can speed up navigation, and it's well worth defining keys for the 'Select Track: Next' and 'Select Track: Prev' commands (which are found in the Key Commands window's Project section). As you navigate with these keys, the Channel Settings window will automatically refresh to reflect the selected track/channel. It's very slick and well worth a tick in the 'ease of use' box.

For Better Or Worse

To finish, one further Channel Strip/EQ workflow tip is worth mentioning. When editing multiple channels, such as the drum kit recording in the example, I often find it useful to toggle all my Channel Strip and EQ settings off, for an A/B reality check as to whether my processing is actually making things better or worse! In practice, this can be a bit of a pain, as in the MixConsole you have to bypass both the Channel Strip and EQ Racks individually for every channel involved to do this. Now you could, I suppose, go to town and design a macro to solve that... but a simpler approach is to quickly select multiple channels and then press and hold Alt+Shift to temporarily 'Quick Link' them. Then, when you click on the bypass buttons on any of the selected EQ or Channel Strip sections, those Rack sections will be bypassed for all selected channels simultaneously.