Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions. Where there are no limits! Enjoy your visit!

Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions

| Company Founded | 2005 |

|---|

| Overview | Our services include Sound Engineering, Audio Post-Production, System Upgrades and Equipment Consulting. |

|---|---|

| Mission | Our mission is to provide excellent quality and service to our customers. We do customized service. |

Thursday, October 31, 2024

Wednesday, October 30, 2024

Multitracking Drums

Our starting point, the mutitrack drum comp. In this case, it's a simple 12-bar drum part.

Our starting point, the mutitrack drum comp. In this case, it's a simple 12-bar drum part.

Last month, I explained how to 'comp' a performance from multiple-take multitrack recordings, using Cubase 6's Group Editing features. That's great if the takes are perfect, but there are times when even a decent drum performance can benefit from slightly tightened timing. Fortunately, Cubase 6 offers the means to do this for multitrack audio recordings.

The audio-warp facility can be used to time-stretch and quantise audio events, but for quantising multitracked drums, slicing at hitpoints provides better results. Group Editing is the key to this slicing process, because it ensures that each track is sliced at exactly the same points, and that slices from different tracks stay locked together in time — thus avoiding the pitfall of tracks being moved out of phase alignment.

Consolidate

Let's assume you've completed the comping process described last month: you've identified the best bit of each take and set the required sub-sections of each take to have playback priority. To apply some quantise options to the multitrack audio, you need to identify the hitpoints (in the case of drum tracks, the start of each drum hit) and then slice the audio. To perform these operations, it's helpful to have each track rendered to a single, continuous audio event. Check that the Folder Track still has the Group Editing switch engaged (the button that looks like an '=' symbol in the Group Track header), and then select all the audio events on the drum tracks and apply the Audio / Bounce Selection function. The sub-sections of the various takes will be combined into a single audio event for each track.

Hit Me Baby

The comp after applying 'Bounce Selection'. Each track now contains a single audio event, which can be used to generate hitpoints.

The comp after applying 'Bounce Selection'. Each track now contains a single audio event, which can be used to generate hitpoints.

The next step is to add hitpoints, using the Sample Editor. Kick and snare close-mic tracks are usually the best candidates, as a suitable threshold setting (one that identifies all the drum hits but is not so sensitive that the bleed from other drums also creates hitpoints) is usually easy to find. Not all cases will be simple, though, and, depending on the amount of bleed between mics, some manual editing may be required to remove hitpoints triggered by undesirable sounds. Individual hitpoints can be disabled by Shift-clicking. For maximum flexibility, add hitpoints to each track that you think controls the overall drum groove.

Nicely Sliced

Hitpoints need to be created in the Sample Editor for each of the key drum tracks.

Hitpoints need to be created in the Sample Editor for each of the key drum tracks.

Back in the Project window, select all the drum-track audio events (with Group Editing switched on, selecting an event on one track will automatically select corresponding events on the other tracks). Then open the Quantize Panel, which is accessed via the Edit menu. If all goes well, you should see at least two sections in this panel: Slice Rules and Quantize. A third (Crossfades) will appear later in the process. I say 'if all goes well', because Cubase sometimes decides that the conditions are not quite right for audio quantising via a Group edit. The key issue seems to be that the audio events on each track must be exactly the same length.

The Slice Rules section allows you to attach a different priority to each track for which you've generated hitpoints. Which tracks are attached the highest priority obviously depends on which drum element you deem to be the most important in terms of the groove, but it's well worth experimenting a little here. Hitpoints that are going to be 'active' in any slicing are displayed in red, and if you adjust the track priorities you can see these change.

The two other Slice Rules settings are Range and Offset. Range simply identifies how close two hitpoints on different tracks can be before they're considered to be the same (with the higher priority track taking precedence), and Offset determines whether the slice point will be at the exact position of the hitpoint or slightly before. The default offset is -20ms, so the slice is going to be placed before the hitpoint and, therefore, before the attack of the drum hit. (If this sounds strange, you'll see shortly that it's actually very sensible!)

Pressing the Slice button separates the audio on all tracks at each of the red hitpoints, so slicing occurs at exactly the same place on every track in the group. If you're not satisfied with the result, the double-headed arrow icon at the bottom-left of the Slice Rules section is a 'reset' button: it retains your carefully crafted hitpoints but returns the audio to its original unsliced state so you can try again.

Let's Swing

The Quantize Panel's Slice Rules set the priority given to each track's timing. Its central section allows you to define the quantisation type.

The Quantize Panel's Slice Rules set the priority given to each track's timing. Its central section allows you to define the quantisation type.

Once the multitrack audio is sliced, use the central Quantize section of the Quantize Panel to adjust the timing of the performance. These controls are almost identical to those used when quantising MIDI, so they should feel familiar to most Cubase users. There's plenty to experiment with, from simple tightening of timing by setting a grid resolution, to adding a bit of swing to that grid, or applying a groove quantise based on a groove from another performance.

There are other useful controls, too. The Catch Range setting is useful for more complex material, as it allows you to restrict quantising actions to the hitpoints that are close to the major grid beats. If you want to avoid things feeling too mechanical, subtle use of the Randomize setting can help (or make your drummer sound sloppy, depending how far you take it!).

It's possible to use the Quantize button to apply the quantise settings you've selected, but engaging the Auto Apply switch means that the audio slices will move around as you change the quantise settings. Whichever way you approach this, note that when slices move, the corresponding slices on each track stay locked together — so if slice three on the kick track is moved by the quantise process, slice three on all other tracks will move with it, which keeps the phase relationships between the tracks correctly aligned. Brilliant!

Not Fade Away

The Crossfades section can smooth out the transitions between each slice and, because of the Offset setting in the Slice Rules section of the Quantize Panel, the crossfades can be positioned prior to the actual hitpoints and therefore do not interfere with the actual drum hits.

The Crossfades section can smooth out the transitions between each slice and, because of the Offset setting in the Slice Rules section of the Quantize Panel, the crossfades can be positioned prior to the actual hitpoints and therefore do not interfere with the actual drum hits.

Moving slices can open up 'gaps' in the audio between adjacent slices, or make some slices overlap. A third section of the Quantize Panel, called 'Crossfades' can be seen in the example screen shot, and this only appears once you've pressed the Slice button. When you've quantised the audio to your satisfaction, a quick press of the Crossfade button will close the gaps between the slices and apply a crossfade (the length of which is governed by the Length setting) between each slice. It's at this point that the need for the Offset setting in the Slice Rules section becomes apparent: slicing a small distance before the drum hit means that the crossfades between adjacent slices can be made to fall into this area, rather than across the drum hit itself — so the hits don't suffer. In most cases, applying these crossfades tidies things up nicely.

All being well, you should now have compiled your best multitrack drum part, and enhanced it further using glitch-free multitrack quantising. If not, it's easy enough to go back and tweak the quantise settings further, as the fades will adjust themselves as you do.

All this said, making audio quantise work smoothly requires practice, so to begin with I'd suggest that a KISS (keep it simple, stupid!) approach is the right way to go: try working with some less complex drum performances at first, where there are fewer hitpoints to worry about. Once you've mastered the mechanics, you can explore the potential for correcting, or adding a little post-recording groove to more complex drum tracks.

Beware Rigidity

It's easy to overdo quantisation, particularly if you're quantising to the grid at a fixed tempo. You might want your drummer to sound like a robot, but most of us don't — so experiment with the amount of quantising you apply. If you want to go further, you could investigate the possibility of adding a more natural quantise groove to your production — but that's a topic for another month.

Tuesday, October 29, 2024

Monday, October 28, 2024

Control Room

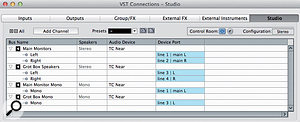

Configuring two sets of stereo monitors in the VST Connections dialogue.

Configuring two sets of stereo monitors in the VST Connections dialogue.

In last month's Cubase workshop, we looked at how you can create up to four unique headphone monitor mixes for your recording musicians, using the Studio channels in Cubase 6's Control Room, and we saw how the ability to create these alternative monitor mixes can be just as useful for the solo musician. Artist monitor mixes are not the only trick up Control Room's sleeve, though, and this month we'll focus on how it can be used in place of a traditional console or hardware monitor controller to switch between multiple monitoring systems in your studio.

Mix Translation

Having spent lots of time lovingly crafting your mix to the point of perfection, it's a great feeling when you feel the hairs on your neck tingling. So you take a copy to your band-mate's house... and experience the nastiest of surprises when it sounds horrible on their playback system. What went wrong? One obvious answer that we often explore in these pages is that you need to improve your studio acoustics; but it could also be that you need to check your mixes on different speaker setups. For example, the bass might sound and feel amazing on your full-range monitors, but be inaudible on someone else's speakers.

The Control Room Mixer can be used to switch between the different monitoring systems via the A and B selection buttons located at bottom right.

The Control Room Mixer can be used to switch between the different monitoring systems via the A and B selection buttons located at bottom right.

Look at the top-notch studios that are often featured in the pages of SOS, and you'll usually see more than one set of speakers in the control room. You might also see a mono grot-box, and there's probably a decent set of reference headphones on hand somewhere too. By checking your mix on these different speakers, the aim is to pick up problems that you miss on the others, and thus to produce a mix that works well on various playback systems.

If the pros need to do this in studios where cash has been splashed on creating the perfect listening environment, you can bet that it's even more essential in an average home or project studio, housed in a spare bedroom or a garage!

Hardware Matters

To work with multiple monitoring systems, you could juggle lots of patch cords, or invest in a mixer or outboard monitor controller, but assuming you have a multi-output audio interface, Cubase's Control Room can plug the gap, allowing you to switch between systems with nothing more than a mouse click.

We'll look at a simple example: switching between a main set of nearfields and a pair of domestic hi-fi speakers — but the more ambitious amongst you should note that the Control Room allows you to switch between surround sound, stereo and mono systems if you need to. I'll come back to the issue of mono a little later.

Assuming you have the necessary speakers, you'll need to make sure you have sufficient physical outputs available on your audio interface into which you can hook up your amps and/or speakers. For my example, my setup requires four outputs (two stereo pairs).

Control Room Setup

The MinConvertor provides a downmixing facility, to check mono compatibility.

The MinConvertor provides a downmixing facility, to check mono compatibility.

With your various speakers connected to your audio hardware, you need to configure the Control Room to allow them all to be used. To do so, you need to open the VST Connections window (from the Devices menu), select the Studio tab and then ensure that the Control Room is switched on (when it is, the power button icon becomes blue).

Then add the necessary output channels for your various speaker sets. In the illustrated example, I've added two stereo outputs; one for my main nearfield monitors and one for my hi-fi speakers. I've then clicked in the Device Port column to assign each speaker to the appropriate output on my interface. For this example, that's all I needed to do.

Time To Switch

The appearance of the Control Room Mixer (also opened from the Devices menu) will change to reflect the settings made in the VST Connections window. In the example, I've again kept this simple (for example, there are no Studio, Talkback or Headphone channels shown). Located at the bottom of the Main Monitors channel is a tiny box that lists the different output channels you have configured in the VST Connections window. In this screen, this list comprises my Main Monitors (output configuration A, highlighted in blue here as this is the currently selected output) and my grotbox speakers (output B).

Switching between the different speakers is then simply a matter of clicking on the appropriate button (A or B) and, usefully, this can be done on the fly during playback. Note that you can also click on the larger button located immediately to the left, to toggle between each of the output sets in turn. Usefully, the buttons light up in orange for your additional monitor sets, rather than the blue used for your main monitors, and this is a useful visual reminder of which is currently selected.

A DAB Hand

The Preferences page for the VST Control Room.

The Preferences page for the VST Control Room.

If you plan to have your music used in a broadcast context, the odds are that some listeners, either via a radio (weak FM signals collapse to mono, and the world's biggest selling DAB radio has only a single speaker!) or older TV set, will hear at least some of your mix in mono — so just as it's important to cross-reference your mix between different monitoring systems, it's important to check that the mix works well in mono. This can be particularly problematic if you use lots of hard panning, stereo widening or modulation effects, as these can often respond unpredictably when things are mashed down to a single mono speaker, with elements sounding dulled or even disappearing completely, due to phase-cancellation. There's always some trade-off between mono and stereo mixes, but you need to be able to hear what's happening to find the right balance.

Fortunately, the Control Room Mixer makes it easy to check mono compatibility. Just above the monitor-selection box is a second box. In the example screenshot, this presents two options: stereo (numbered 1, currently selected and shown in blue) and mono (numbered 2). There might be others there if you have, for example, a surround-sound playback system as well. If you select the Mono option, Cubase makes use of its MixConverter settings to downmix the stereo into mono: essentially, the same signal is sent to both speakers, creating a phantom mono image that appears to sit between the two speakers. (View and configure the MixConverter settings by clicking the small downward arrowhead located just above the box itself). You can use this downmixing function for any of the monitoring systems that you've configured in the Control Room.

There is one further trick here, though. As described by Hugh Robjohns in the Q&A/Sound Advice section of SOS February 2011, listening to a simulated mono mix is not quite the same thing as listening on a single mono speaker, where all sound is coming from the same source: the latter approach paints a more reliable picture. If you have sufficient audio outputs and speakers, you could configure a further Control Room output to feed a mono signal to a single speaker, but if you don't have enough outputs or speakers it's possible to use just one of an existing stereo pair.

Configuring the Control Room outputs to provide a mono monitoring system using just a single speaker from your standard stereo monitoring system.

Configuring the Control Room outputs to provide a mono monitoring system using just a single speaker from your standard stereo monitoring system.

To configure such a system, you need to visit the VST Control Room section of the Preferences dialogue box. Here, you need to uncheck the 'Exclusive Device Ports For Monitor Channels' option, which is switched on by default. Unchecking this allows you to assign the same hardware audio output to more than one of your monitor setups within the VST Connections dialogue. You might do this if, for example, your main stereo monitors were also used as the front left/right monitors in a surround system. You can then return to the VST Connections window, create a new mono output channel and assign it to the hardware output using either your left or right monitor. As shown in the screenshot, I've done this both for my main nearfield monitors and my grotbox speakers. These monitoring setups get added to the list in the Control Room Mixer, and you can switch between any combination of stereo, simulated mono and true mono, as required. Neat!

On Me Head, Mate!

Headphones provide a very useful alternative monitoring reference, and good headphones can be particularly useful for hearing tiny details in the mix. In many audio interfaces, the headphone and main stereo outputs are fed the same signal, so to 'switch' to that, you just stick the headphones on your head, and maybe turn up the headphone volume knob. The Control Room, though, features a dedicated headphone channel, and if you have the appropriate hardware, you can configure it as part of the Control Room switching system — and keep your headphones at a consistent level without them leaking into your speaker mix or you ever having to reach for the volume knob!

Saturday, October 26, 2024

Friday, October 25, 2024

Steinberg Cubase 6.5

Don't panic: Cubase hasn't gone brown for 6.5, this is just how I like it! Above is the new comping tool, which can be used with the group-editing feature to save hours of tedious multitrack editing.

Don't panic: Cubase hasn't gone brown for 6.5, this is just how I like it! Above is the new comping tool, which can be used with the group-editing feature to save hours of tedious multitrack editing.

As a long-time Cubase user, I've seen many major updates to Steinberg's flagship music-production software, and the latest brings us up to Cubase 6.5. Updates are available both for the full version, as reviewed here, and for Cubase Artist.

Cubase 6.5 does not at first sight appear to be the most major of overhauls, and some users have complained about having to pay for a '.x' version. But after evaluating v6.5 for several weeks, I don't agree: there's some really useful new functionality, and significant enhancements to existing facilities that should prove worth the modest upgrade price. Version 6.5 also includes plenty of bug-fixes, and when it was first launched, this was the only way you could get hold of them. Since then, these fixes have been incorporated in Cubase v6.0.7, which is a free update for Cubase 6.0.x users (for full details, and to download the updaters, go to www.steinberg.net/forum/viewtopic.php?f=34&t=21918).

So what exactly does your money buy you with Cubase 6.5? Notable additions include two new VST synths and a couple of new EQ and filter plug-ins, as well as an update to the VST Amp Rack guitar amp, cab and effect modelling plug-in. There's also much-requested support for 64-bit ReWire (yes, it works — and there's very little else to say about that!) Finally, there are a number of new features designed to streamline editing and the comping of multitrack recordings.

OK Comp-uter

The first feature worth writing home about is a new dedicated comping tool, intended to streamline the process of piecing together the perfect virtual performance from a number of different takes. Its icon looks like a pointing finger, and can be accessed from the same tool palette that offers scissors, glue tool and so on. I'm pleased to report that it promises a significant reduction in the number and intensity of headaches caused by intensive comping!

The way it works will be familiar to users of some other DAWs, notably Apple's Logic Pro, which I believe was the first to adopt this approach. With the different takes displayed beneath each other on lanes, all you need to do to comp the perfect performance is select the comp tool and 'paint' the areas on the different takes that you wish to hear. This is a vast improvement over the previous system, where you had to use the pointer, scissors and mute tools to identify and bring to the 'front' the elements you wished to comp together. It has made this common task both easier and faster.

Steinberg have gone a step further, though, by adding some useful menu options. When you've selected the desired regions of your comp takes, you can right-click (Ctrl-click on Mac) to access a small drop-down menu offering an automatic Clean Lanes function, which takes care of the minutiae, such as overlapping takes. The same menu also features a Create Tracks From Lanes function which 'mults' out each lane, complete with comp selections, to its own audio track, on which you're able to alter levels, add effects and perform all the usual operations you might do on an audio track. This means that, as well as comping with it, you could use this tool as a convenient method of picking out the odd word, phrase or note to be treated with spot effects while mixing or remixing.

For me, the new approach to comping alone would be worth the upgrade price, but it gets better: when used in combination with the group-editing functions that were introduced in Cubase 6.0, it can save quite literally hours of tedious editing of multitrack, multi-take parts such as backing vocals and drums. As with all group editing, all you need to do is to make sure the multi-mic recordings are on adjacent tracks, select all the tracks, right-click and choose the Move Selected Tracks To New Folder option. On the new folder track, you click on the '=' icon beneath the mute and solo buttons to enable group editing, then select your comping tool and get to work.

It really is that simple — and it worked flawlessly in my tests, except when I'd inadvertently included a wrong audio track in the same folder. In this scenario, you'll get a helpful warning that not all the files are in sync, which denotes that you've either inadvertently nudged a track, or included one in the folder that shouldn't be there (from a different instrument, for example). This is a most welcome addition to Cubase. If I were looking to buy a plug-in to do such a job (if one existed), I'd expect to pay a fair whack for it, so the modest upgrade price is beginning to look very reasonable.

One very minor issue that I noticed while testing this new function isn't new to v6.5 but is worth a brief mention in case anyone reading gets confused by it: when in group editing mode, it's still possible (admittedly via a somewhat convoluted route) to throw group comps out of sync, by double-clicking on a part to open the track's sample editor and changing the start and end point of a region on that track. When you return to the Arrange page, you'll find that the region length has only changed for the selected track, not for the others in the group — and because of this, that one track's comp selection will no longer quite match that of the others in the group. It's a loophole which ideally Steinberg will close, but the easy way for the user to avoid this, of course, is not to be stupid enough to do this sort of edit in group mode in the first place — and now you're forewarned, you've no excuse!

Come Together

The ability to slice, quantise and stretch audio has been present in Cubase for a while now, and although the tools work well, I've always felt that they should be rather better integrated — and so too, apparently, did Steinberg, because in 6.5 they've overhauled all of this, making the various tools work much more closely together. It's easy to overlook this sort of improvement because there aren't really any new functions here — you can't do anything you couldn't do in Cubase 6 — but it's a very useful rationalisation of what went before.

By way of example, when you detect hitpoints, the same window now presents you with the opportunity to create warp tabs or markers based on the position of each of those hitpoints. Previously, you had to perform a number of separate steps to achieve the same result.

Imports & Exports

Further potentially useful enhancements include the ability to publish your mixes directly to your SoundCloud site. Once your SoundCloud details are set up, all you need do to achieve this is tick the following option: Export/Audio Mixdown/PostProcess/Upload To SoundCloud. Cubase will then upload the stereo mix to Soundcloud after performing the bounce. (Just don't forget to check the file for errors, as you would with any other bounce!)

A more useful facility for me is the support for FLAC audio files. FLAC is a lossless data-compression format for audio, and it now appears in the list of import/export options. I can see this being incredibly useful to anyone wanting to archive projects or media pools to DVD, for example.

All this talk of imports and exports also provides me with a rather tenuous segue to the fact that Cubase now supports the Chinese language. I'd love to be in a position to say that I've tested that, but I'm afraid that the only kind of mandarin I'm familiar with is a small, orange and refreshingly juicy citrus fruit!

The Main Grain

Cubase has, perhaps unfairly, developed a reputation for lacking the virtual-instrument firepower available to owners of, say, Logic, Sonar or Pro Tools. Personally, I had very few problems with the existing synths, and have happily made use of Monologue, Prologue and Embracer despite possessing several costly third-party VST instruments. Sure, there are better soft synths out there, but as a starting point, these were capable of creating an extensive and very usable sound palette. The new Retrologue and PadShop VST synths.

The new Retrologue and PadShop VST synths.

Nonetheless, Steinberg clearly thought that there was room for improvement and they've done their best to fill it with a granular synth, PadShop, and a subtractive analogue-modelling synth, Retrologue. Both are completely new, and are included in the full and Artist versions of Cubase. PadShop is also available separately (for the same price as the full Cubase upgrade), for use in other VST3 hosts, such as Presonus Studio One and FL Studio.

Both synths sound pretty good, to my ears, and are very different from Steinberg's previous offerings. PadShop does much what you'd expect of a granular synth: it's great for creating breathy or bell-like, evolving, other-worldly soundscapes, for example. There are around 400 presets, and a number of controls both for the granular part of the synth, and for the obligatory filter, amplifier and other control sources (including two LFOs and a step modulator). Modulation and delay effects are built in.

Using PadShop is a breeze. Everything's nicely laid out and the controls are pretty intuitive. The results sound pretty decent to my ear, as well. However, a significant disappointment is that PadShop appears to work only with its own bundled audio files: I was unable, for example, to take an excerpt from an audio file in the project I was working on, or a sample from my existing library, and use that as the starting point for a new sound in PadShop. That's a shame, as to me that's part of the fun of playing with a granular synth, so let's hope it gets added in future. Nonetheless, the plentiful presets mean that this synth is still capable of creating a wide range of useful sounds, and it should have appeal for anyone wanting to add texture to electronica or dance tracks, or perhaps people looking to write atmospheric soundtracks.

Retro Chic

Retrologue is much more my cup of tea, and will feel familiar to anyone who's ever programmed a subtractive analogue synth. It's a much richer, warmer-sounding creation than Steinberg's previous offerings: it sounds much better than either Monologue and Prologue, which is a pleasant surprise. The sound is created by three oscillators and a noise source. The two main oscillators offer a wide range of waveforms, as well as an intriguing 'cross' mode, where the two interact. For each, the pitch is set in three degrees: the octave, the semitone (coarse) and cents (fine). A sub-oscillator offers a choice of square, sawtooth and triangle waves, and the noise source provides pink and white noise, both 'clean' and band-pass filtered. A mixer sets the relative levels of these sources, and provides a ring modulator. The filter section offers a choice of 12 different filters, as well as a choice of tube distortion or clipping, and the usual ADSR filter envelope, and there's another ADSR for the amp. There's also the usual choice of modulation and delay effects. Then, of course, there are the two LFOs, each delivering one of six waveforms, which can be tempo-sync'ed if required. I was mildly disappointed to find there was no audio side-chain input for the LFO, which would have been a nice touch for creating more complex control modulations.

The icing on the Retrologue cake, though, is the Matrix section, which enables the user to set up some pretty sophisticated control-source routing. As well as the usual LFOs, mod and pitch wheels, filter and amp envelopes and the like, you can select VST note expression inputs as the source. You can also set up routing buses within the Matrix, which gives you a massive degree of control if you're prepared to put the time into programming your own patches — and if you're not, again there's a generous complement of presets that will satisfy the lazier composers amongst you! All in all, then, this is a decently specified synth, and it sounds damned good to boot.

New Filter Plug-ins

As I mentioned at the outset, there are also a couple of new filter plug-ins, Morph Filter and DJ EQ. Essentially, the Morph Filter offers a useful range of high-, low- and band-pass resonant filters, and allows you to blend between two of them at once. Again, it's a useful addition, particularly if you want to perform automated filter sweeps, and although it's hardly the most ground-breaking of tools, it works really well and sounds good. Also new are the DJ EQ and Morph Filter plug-ins.

Also new are the DJ EQ and Morph Filter plug-ins.

DJ EQ is, as the name suggests, a 'kill' EQ. It provides three EQ bands which can be boosted or cut to shape the sound as desired, and a kill switch for each band allows you to toggle between the boost/cut you've applied and complete removal of the band. To me, it's more of a performance effect, as its name implies, which might best be used in conjunction with a control surface of some sort — but I can see that it could also be used with automation to create interesting remix effects.

VST Amp Rack

With the exception of the old Quadrafuzz plug-in, for which I always had a soft spot, the VST Amp Rack plug-in is the first of Steinberg's guitar processors that I've really liked. The VST Amp Rack has been overhauled and includes some new plug-ins. In Cubase 6.5, it has been developed further and it really is maturing nicely, with a few new features and plenty of new presets. The bottom line is that it sounds rather good, with several really usable amp and cab models, a decent array of effects that can be inserted pre- or post-preamp section, and a handy master section. We've also been given a couple of useful new effects for VST Amp Rack, a maximiser and a limiter, both workmanlike and welcome additions, but their presence does make me wonder why there aren't VST insert slots that allow you use Cubase's existing complement of processors and effects in VST Amp Rack.

The VST Amp Rack has been overhauled and includes some new plug-ins. In Cubase 6.5, it has been developed further and it really is maturing nicely, with a few new features and plenty of new presets. The bottom line is that it sounds rather good, with several really usable amp and cab models, a decent array of effects that can be inserted pre- or post-preamp section, and a handy master section. We've also been given a couple of useful new effects for VST Amp Rack, a maximiser and a limiter, both workmanlike and welcome additions, but their presence does make me wonder why there aren't VST insert slots that allow you use Cubase's existing complement of processors and effects in VST Amp Rack.

I do have one reservation, which is by no means a deal-breaker. When inserting this plug-in, there was a significant boost to the level of the signal, sufficient to clip at the output or in subsequent plug-ins in the chain. (I suppose you could argue that an amplifier should boost signals, but it's not massively helpful in a DAW context!) On the plus side, the plug-in now features both input and output level metering, so it's easier to see what's going on in this respect.

Verdict

As I stated at the outset, this is a genuinely useful update to Cubase, and if you're wondering whether to updgrade from Cubase 6, I wouldn't blink: it's well worth the asking price. If you're looking to buy Cubase for the first time, while it — just like any other DAW — is not going to please all of the people all of the time, I think the traditional criticism of its bundled plug-ins, limited routing flexibility, multitrack editing and so on are now out of date.

With VST Amp Rack coming of age, a decent complement of synths, drum instruments and sample-based instruments, a great-sounding convolution reverb and an ever-growing list of bundled plug-ins, it's fair to say that Cubase has very much caught up with the pack in this respect. In other areas — such as groove and hitpoint detection, quantisation, multitrack comping and pitch and time manipulation, it's now up there with the best. And let's not forget that there are still more features (like the drum editor) that have been around for a while and are, for me at least, easier to use than on any other DAW. Certainly, whatever your DAW preference, it's hard to argue that anything else offers a great deal more functionality. And while the full price can at first appear a little daunting in comparison with that of some other DAWs (notably Apple Logic, Ableton Live, Cockos Reaper and Presonus Studio One), it bears comparison with others, such as Avid's Pro Tools 10 and Magix's Samplitude Pro X, and is not unreasonable.

Installation Teething Troubles

I've read a number of reports on the Internet of users suffering with installer problems in Windows, and should mention that I had frustrating time of it myself. The full installer is a hefty 8GB or so, so I opted to download the smaller update from Cubase 6.1. Unfortunately, the installer was corrupt: after three separate download attempts, it kept hanging when trying to unpack some files associated with PadShop. Retreating from that battle, I gritted my teeth and downloaded the full installer which worked fine on the second attempt (the first worked, but the PadShop source WAVs weren't installed). The exception was that I lost my Cubase 6 preferences. It took a while but, as you can see from the gloriously brown screenshots, I was able to retrieve the original XML preferences file! I should stress that there are plenty of people who have had no problems, and that after early problems with updater files for Windows, Steinberg made a new version available. In any case, I'd suggest that you stick with good practice and set a restore point on your operating system prior to installation.

Pros

- New comping tool is simple and effective, and makes multitrack comping a breeze.

- Retrologue synth sounds great, and PadShop extends the sound palette nicely.

- Rationalised hitpoint, groove, warp tab and marker functions are a real time-saver.

- VST Amp Rack keeps getting better, and is now rather good.

- FLAC support saves disk space without compromising audio quality.

- Direct export of the mix to SoundCloud.

Cons

- PadShop can't import external audio files.

- A few installation teething troubles.

Summary

While the headline updates don't appear, at first glance, to add up to a great deal, this is actually one of the most useful Cubase updates yet, and the program is maturing nicely. There are valuable additions for programmers and synth heads, as well as for anyone doing serious mixing and editing. The new group comping tool is probably worth the upgrade price alone if you often work with layered backing vocals or multitrack drums.

information

Thursday, October 24, 2024

Wednesday, October 23, 2024

Groove-quantise, Part 2

Part of the drum loop showing in the Sample Editor. Note the low threshold setting to ensure that all of the drum hits — loud and quiet — have a hitpoint associated with them.

Part of the drum loop showing in the Sample Editor. Note the low threshold setting to ensure that all of the drum hits — loud and quiet — have a hitpoint associated with them.

In last month's Cubase column (/sos/jul12/articles/cubase.htm), I explored how to use Groove Quantize to extract the subtle rhythmic and dynamics variations that make up the 'groove' of one MIDI part, and apply them to another. Although the mechanics are slightly different, similar techniques can be used with audio parts, and that's our subject here. If you want to know more about grid-based quantisation of multi-miked, multitrack, audio (for example, from a drum kit) check out the workshop in SOS March 2012.

Prepare To Groove

To prepare the audio for groove quantising, I'll use a similar example to last month — taking a groove from a short (stereo) drum recording and applying that to other parts, such as bass and rhythm guitar. Imagine that the bass and guitar were originally recorded to a different drum performance but, in order to spice things up a little, the drum part has been replaced with a new recording which has a slightly different feel (more funky) than the original. So the task is to keep the bass and guitar parts, but give them a little more of the groove from our new drum performance.

First, double-click on the drum audio event to open it in the Sample Editor. You can now adjust the Threshold setting under the Hitpoint tab, to identify the key drum-hit thresholds. When working with drums, I tend to use a relatively low Threshold setting to capture even the quieter hits (in this case, from the hi-hat), but if Cubase has identified some additional spurious hits, you can manually disable individual hitpoints: with the Edit Hitpoints button engaged, hold down the Shift key and click on them (and move them if you don't think the algorithm has got the positioning spot-on). Don't forget the Remove All button if you decide to start from scratch.

Extraction

Adding hitpoints to the bass part. As well as the notes starts, this also created two hitpoints at the ends of notes (just after the start of bar 14 and bar 15) that I disabled prior to quantising.

Adding hitpoints to the bass part. As well as the notes starts, this also created two hitpoints at the ends of notes (just after the start of bar 14 and bar 15) that I disabled prior to quantising.

Having generated and sorted your hitpoints, you can make a groove preset from them directly from the Sample Editor window, via the Edit menu, or by dragging and dropping to the Quantize Panel, and it's worth noting that these three different methods don't always seem to produce consistent results (nope, I've no idea why either!). Personally, I tend to stick with the second approach, but see which works best for you.

With the drum part selected in the Project window, select the the Edit/Advanced Quantize/Create Groove Quantize Preset menu option. This uses the full length of the audio event to create the groove preset. Once done, make sure you save the preset (the name has an asterisk at the start of it when it has not been saved) and give it a meaningful name.

Groovy Application

To apply your groove to another audio performance, two different approaches may be used: AudioWarp and slicing.

For non-drum-based material, such as bass and rhythm-guitar parts, the AudioWarp approach can produce pretty decent results. First, create hitpoints for the audio that's to be quantised. When we later quantise the part, AudioWarp will time-stretch/compress the parts being quantised, so that the hitpoints align more closely with those in the groove preset.

As with any time-stretching process, though, if you ask too much of AudioWarp you can end up with all sorts of unpleasant audio artifacts. This is one reason why I suggested starting with a low hitpoint detection threshold when creating your groove preset: because there are a lot of hitpoints, it's less likely that the quantise process will have to stretch or compress any individual bit of your target audio too far.

For the bass and rhythm-guitar parts used in this example, the Quantize Panel's AudioWarp option produced the smoothest results, but quantising based on sliced audio is also possible.

For the bass and rhythm-guitar parts used in this example, the Quantize Panel's AudioWarp option produced the smoothest results, but quantising based on sliced audio is also possible.

For the target audio, I prefer to create the required hitpoints via the Sample Editor, as it lets me fine-tune the process. A hitpoint at the start of each note or chord is a good starting point, and this can easily be checked by auditioning individual slices within the Sample Editor. As shown in my bass-guitar example, the hitpoint-detection process will sometimes be fooled by things like finger or fret noise at the end of notes and chords, and I tend to find that I get smoother results if I disable these hitpoints in the Sample Editor prior to applying any quantisation. Cubase can add hitpoints automatically for you when you select the audio event in the Project window and then open the Quantize Panel — but you don't get the same level of control if you use that method.

Once you've created and fine-tuned the hitpoints, open Cubase's Quantize Panel, select the groove preset and engage the AudioWarp button. For more gradual control over the quantise process, the iQ (iterative quantise) mode is useful: as the name suggests, this allows you to get closer to the groove by degrees, rather than snapping wholly to the groove, and this means that you can make the timing progressively tighter.

As shown in the screenshot, for both the bass and guitar parts used here a setting of 25 percent for the iQ and Position controls provided a good starting point, as it allowed me to repeatedly press the Quantize button and listen as the audio was gradually quantised a little more firmly with each iteration. In addition, a Max Move setting of 16th or 32nd intervals stopped the quantise process from moving any hitpoint too far from its original position, ensuring a smoother end result.

Nice Slice Baby

A short section of the bass and rhythm guitar tracks with both the unquantised (blue) and quantised (red) versions shown. As an example, see how the note or chord at the cursor position has been pulled forward in time in the quantised versions and now coincides with the drum hit at the same time position.

A short section of the bass and rhythm guitar tracks with both the unquantised (blue) and quantised (red) versions shown. As an example, see how the note or chord at the cursor position has been pulled forward in time in the quantised versions and now coincides with the drum hit at the same time position.

Slicing is probably best used with audio tracks containing very sharp transients, such as drums or percussion, although there's nothing to stop you trying it with simple bass or rhythm guitar examples such as those we're trying to 'groove' here. When dealing with a single-track recording (rather than the multitrack drum recordings considered in SOS March 2012), the process is slightly different, as the slicing is done in the Sample Editor. Essentially, you create hitpoints as described above, and then press the Create Slices button to slice the audio at each hitpoint.

Once you've created your slices, the audio event is turned into an audio part in the Project window, containing separate events for each slice. You can now use the same combination of Position, iQ Mode and Max Move in the Quantize Panel as given in the earlier example (but leave AudioWarp switched off). The quantisation is then achieved by simply moving the start positions of each slice within the part to more closely match the hitpoints in the groove.

As with any slicing process, moving slices relative to one another can create gaps and overlaps between slices, so you might also need to tweak the settings in the Crossfade section of the Quantize panel that appears when dealing with sliced audio. Applying a little Nudge to the left can also help, as it moves the position of any crossfade prior to the attack portion of a note, so that the attack itself, which is so crucial to the sound, is not unduly influenced by the crossfade.

Mix & Match

When quantising with sliced audio, the Quantize panel includes the Crossfades section.

When quantising with sliced audio, the Quantize panel includes the Crossfades section.

You can, of course, mix and match groove quantising between MIDI and audio parts, so if you've captured a good groove from a MIDI part, it's perfectly possible to experiment with applying it to an audio performance (and vice versa). As with the MIDI groove quantise tasks described last month, the best way to get used to these tools is to start with something simple like a short two-, four- or eight-bar phrase for your drum, bass and rhythm-guitar tracks. If you can get those to lock together well they can be looped to build a song section, and the process can be repeated for other song sections, as required.

Finally, I'll leave you with a handy tip: groove quantising can also be used to create convincing double-tracked guitar parts from a single guitar take. For example, if you take the kind of rhythm-guitar loop that I've used here, you can duplicate the track and then apply slightly different amounts of groove quantisation to each version, so that their timing is tight without being perfectly matched. Pan them hard left and right and you have instant double-tracked guitars.

If you happen to have recorded a DI'ed version of the guitar performance, you could enhance this effect by inserting a guitar-amp simulation plug-in on each track and dialling in different guitar tones. And, as luck would have it, that's just the kind of thing we will look at in more detail in next month's column on the VST Amp Rack.