Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions. Where there are no limits! Enjoy your visit!

Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions

| Company Founded | 2005 |

|---|

| Overview | Our services include Sound Engineering, Audio Post-Production, System Upgrades and Equipment Consulting. |

|---|---|

| Mission | Our mission is to provide excellent quality and service to our customers. We do customized service. |

Tuesday, October 31, 2023

Monday, October 30, 2023

Eliminating Phase Problems

By Sam Inglis

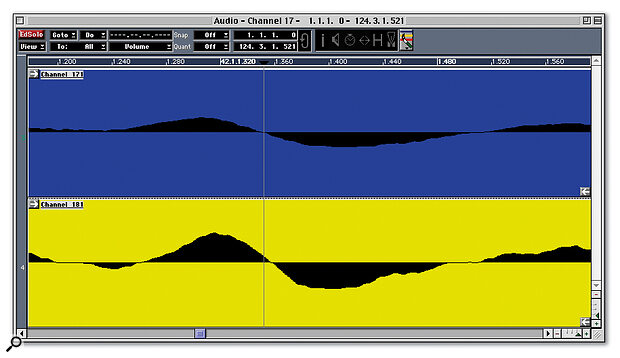

This acoustic guitar was recorded in stereo with the mics at different distances, and consequently suffers from comb filtering when the left and right signals are collapsed into mono — note how the signal recorded with the closer mic (top) is several samples ahead of the other. The Audio Editor's Nudge tool allows us to move parts a single sample at a time to find the best position for phase coherence.

This acoustic guitar was recorded in stereo with the mics at different distances, and consequently suffers from comb filtering when the left and right signals are collapsed into mono — note how the signal recorded with the closer mic (top) is several samples ahead of the other. The Audio Editor's Nudge tool allows us to move parts a single sample at a time to find the best position for phase coherence.

This month, we explain how to eliminate phase problems in Cubase's Audio Editor, and round up some interesting new plug‑ins.

Craig Anderton wrote an illuminating article in SOS July 2001 about the phase problems that can arise when you try to combine miked and DI'd signals from the same source. As he said, this problem is perhaps most common when you're recording bass guitar: the best recorded bass sounds are often those acheived by miking the bass cabinet and blending that signal with the DI'd output from the bass, but because sound takes a finite amount of time to travel through the air, the miked signal is usually delayed with respect to the DI'd one. Signals recorded via a digital processor such as the Johnson J Station or Line 6 Pod will be delayed even more compared with clean DI'd signals. Signals that are not perfectly in phase will exhibit comb‑filtering artifacts, making them sound hollow or thin, and not as loud as they should be.

Phase problems can also result from mic positioning when making stereo recordings, usually where the mics have been placed at different distances from the source. In this case you won't notice that anything is wrong while the stereo signals are panned hard left and right, but when you click the Mono button on Cubase's Master Output, the affected instruments will drop in level compared to the rest of the mix and start to sound comb‑filtered. When your track is based around a stereo recording of something like a piano or acoustic guitar, this can be a big problem: few people listen to CDs in mono, but a lot of people listen to the radio in mono, and the time when your mix is being broadcast to the nation is not really the ideal moment to find out that it isn't mono‑compatible!

As Craig mentioned in his article, when you're working in a MIDI + Audio sequencer, the easiest way to compensate for the delays that cause phasing problems is simply to move one channel's recording forwards or backwards with respect to the other. For this month's Cubase Notes, I thought I'd explain in more detail how to get the best results.

Side Splitting

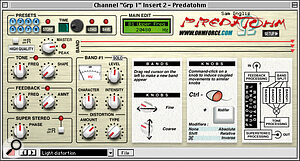

Ohm Force's OhmBoyZ and PredatOhm, in 'funky' and 'classic' skins respectively.

Ohm Force's OhmBoyZ and PredatOhm, in 'funky' and 'classic' skins respectively.

There's no way to persuade Cubase to treat the left and right halves of interleaved stereo audio files independently, so you'll need to make sure that your signals are recorded either as a 'split' stereo file or two mono files on separate tracks (if you want to treat them as a single stereo channel for the purpose of compression and effects, just route them to a group channel in the VST Mixer and add the effects there). I usually record stereo‑miked instruments like this anyway, by using Cubase's Multirecord function to record from two separate mono inputs onto two separate mono tracks simultaneously. If you're stuck with an interleaved stereo AIFF or WAV, you'll need to split it using an external audio editor: the shareware D‑Sound Pro editor on the Mac, for instance, makes it easy to save out the left and right halves of stereo recordings as separate files. You can then import these into fresh mono tracks in Cubase and mute the original stereo recording.

One of the nice things about Steinberg's Nuendo is that it allows sample‑accurate editing and positioning of Events in the main arrange window. Sadly, Cubase doesn't: you'll notice that even with Snap off and horizontal zoom set to maximum, there's a limit to how accurately you can position an Event in time. To make the sort of fine adjustments required to tackle phase problems, you'll need to use the Audio Editor. Select the Event(s) that make up your recording, and double‑click them or choose Edit from the Edit menu. The Audio Editor should open up, displaying both parts of your recording on separate lanes. Set both horizontal and vertical zoom levels to maximum, and you should see the individual waveforms clearly displayed. If you've recorded your files simultaneously onto an Any track, Cubase will have automatically Grouped them, so you'll need to Ungroup them before you can move the two halves independently. To do this, make sure they are selected in the Audio Editor and choose Ungroup from the Do menu.

The shapes of the two waveforms you've recorded will look very similar, and you should be able to see an obvious correspondence between the peaks and troughs in each part. If there's a phase difference, you'll also see that these peaks and troughs don't line up vertically — one part will be slightly ahead of the other. The difference may be just a few samples, but if the two signals are taken from different sources (as for instance when you have an unprocessed mic signal and a DI that has been sent via a digital processor), it may be much more.

With Snap in the Audio Editor set to Off, you should simply be able to pick up one of the audio parts and move it horizontally until the two waveforms seem aligned. Alternatively, when Snap is Off, the Nudge tool allows you to move audio parts left or right a single sample at a time: choose the Nudge tool from the tool palette and simply click or Option‑click over a part to move it left or right respectively.

Testing By Ear

You can usually get pretty close to the optimum result just by lining the two parts up visually, but obviously what matters most is what it sounds like. When you've got a good visual match, try auditioning every alternative within a few samples either side of that position to find the best spot. In the same way as you might find the right frequency to notch out an annoying ring by using boost EQ to exaggerate a narrow band of frequencies, deliberately putting one signal out of phase with the other can help find the best alignment. Cubase's VST Mixer mimics hardware mixers in most respects, but doesn't offer any facility for reversing the phase of a channel. However, you can use an insert plug‑in such as the freeware Fraser's Phase Switch (check out www.audiomelody.com/Plug‑ins/VSTPlug‑ins/FrasersPlug‑ins2.1.htm) to do the same job — but remember to keep Plug‑in Delay Compensation checked in the Audio Setup window, as inserting a plug‑in can introduce a delay which may mess up your phase adjustments. Reverse the phase of one of the two channels, then adjust the respective position of your audio parts until as much of the signal as possible is cancelled out. When you then put the channels back in the correct phase, you should have found the best position for phase coherence. When you're satisfied with the results, you might want to Group the parts to fix your adjustments.

Current Versions

- PC: Cubase VST/32 v5.0 r6.

- Mac: Cubase VST/32 v5.0 r2.

Cubase Tips

In Cubase's Key Editor, the Quantise parameter not only sets the quantise resolution but also the minimum length of notes that can be drawn in with the pencil tool. With Quantise set to 16, for instance, the shortest note that can be drawn in will be a semiquaver.

When you have a MIDI note selected in the Key Editor, its velocity is displayed above the grid, and clicking on that velocity value with the pointer tool allows you to alter it. If you also have other MIDI notes selected, doing this adjusts the velocity of all selected notes by the same amount. This is a handy way of increasing or decreasing the velocity of lots of the notes in a part without altering their relative dynamics.

If you've never visited Steinberg's Cubase community at www.cubase.net, do give it a try. You'll find plenty of 'official' hints and tips as well as active discussion forums where your posts are moderated and read by Steinberg employees and other Cubase experts.

Plug‑in News

Good‑quality VST plug‑ins continue to arrive at the SOS offices by the virtual truckload. French developer Laurent Rabesahala of Ohm Force has been busy creating two interesting plug‑ins called PredatOhm and OhmBoyZ. The former is a tasty multi‑band dynamics/distortion plug‑in which offers unique possibilities for dirtying up your sounds. You can, for instance, gang the controls together in different ways, so that turning one has a similar or opposite effect on another. In conjunction with the parameter automation available in VST, this has almost limitless potential for weird and wonderful sonic mangling, and manages to eliminate much of the digital‑sounding crunch that often plagues other distortion plug‑ins.

PredatOhm is capable of some pretty extreme treatments — I found it especially effective on drums — but Laurent's second plug‑in makes it sound positively tame. OhmBoyZ combines a VST‑synchronised multi‑tap delay with two independent processing paths, each comprising a vicious resonant filter with distortion and feedback. The sheer range of treatments available is impressive: different presets can turn a vanilla drum loop into anything from a fairly convincing backwards LP to a series of clean pitched tones not unlike a harpsichord.

PredatOhm and OhmBoyZ are available in Mac and PC VST formats as well as PC DirectX and BeOS from Laurent's web site at www.ohmforce.com. In both cases, buyers can choose between 'classic' and 'funky' skins: the latter take up more screen space and are harder to get your head around, but certainly look like labours of love! Laurent has come up with an interesting pricing scheme whereby a mere $9.99 buys you the full working version of the plug‑in, but not the licence to use it in commercial recordings. If you want to use Ohm Force plug‑ins on a commercial release, you'll need to buy the Expert or Pro versions ($59 and $149 respectively for PredatOhm and $79/$199 for OhmBoyZ), which add 'crystal clear' 24‑bit processing modes and full MIDI controllability.

Even better value is MDA's EPiano, which is a completely free VST Instrument mimicking the Fender Rhodes electric piano. The interface is basic, but offers all the parameters you need, and the sound is not bad at all. It won't stop Cubase users cursing Emagic for not porting the full version of EVP88 to VST, but it's eminently usable — and at the price, it's a bargain... EPiano can be downloaded from The Plug‑in Spot (www.pluginspot.com) or from www16.brinkster.com/softcentral/mdavst/.

Saturday, October 28, 2023

Friday, October 27, 2023

Surround Sound Explained: Part 9

Over the past few months, we've seen how it's possible to use analogue or digital mixers designed for stereo mixing to mix 5.1-compatible audio instead, and spoken to various producers about how they've achieved it. However, in most cases, it is of course easier to tackle surround mixing in some kind of software-based mixing environment, as this can be customised to suit the number of channels you're working with far more easily than hardware. This month, for the final part of this series, we look at how the major project studio-oriented MIDI + Audio sequencers currently handle surround. Nearly all of these packages have proper, purpose-built surround support — only Cubase VST does not, and even then it's possible to fudge a way of making it work, though with less flexibility than the competition.

Over the past few months, we've seen how it's possible to use analogue or digital mixers designed for stereo mixing to mix 5.1-compatible audio instead, and spoken to various producers about how they've achieved it. However, in most cases, it is of course easier to tackle surround mixing in some kind of software-based mixing environment, as this can be customised to suit the number of channels you're working with far more easily than hardware. This month, for the final part of this series, we look at how the major project studio-oriented MIDI + Audio sequencers currently handle surround. Nearly all of these packages have proper, purpose-built surround support — only Cubase VST does not, and even then it's possible to fudge a way of making it work, though with less flexibility than the competition.

Steinberg Cubase VST & Nuendo

It's certainly possible to create a limited surround mix using Cubase, but since Steinberg want to differentiate it from Nuendo, there are no built-in features to help you. It's important not to be misled by the various third-party 3D panning plug-ins for Cubase, such as SpinAudio's 3D Panner, Zeep's LocaliserDSP, and Pixelsonic's Surrounder. These all provide an insert effect that can receive stereo audio, pan it anywhere between left, right, centre, and surround outputs, but they then use various surround-encoding processes such as HRTF (Head Related Transfer Function) for use with headphones, or Dolby Pro Logic for speakers, to reduce the output to a stereo signal. While genuinely useful for these applications, they don't let you route sounds to more than two output channels, and are therefore unsuitable for Dolby 5.1 surround mixing.

Steinberg Cubase VST.Nevertheless, we have come up with a scheme that will let you position each channel in any static position in a surround environment (see screenshot). With the default stereo output pair of your soundcard allocated to the Master Channel for front left/right duties, you first need to click the Active buttons for two additional stereo busses in the Master Mixer, and name these 'Rear' and 'Cntr/LFE' in the Master Mixer.

Steinberg Cubase VST.Nevertheless, we have come up with a scheme that will let you position each channel in any static position in a surround environment (see screenshot). With the default stereo output pair of your soundcard allocated to the Master Channel for front left/right duties, you first need to click the Active buttons for two additional stereo busses in the Master Mixer, and name these 'Rear' and 'Cntr/LFE' in the Master Mixer.

Next, rename an unwanted Group channel as 'unused', pull its faders right down, and then route the output of each and every channel required for surround work to this 'unused' Group. Having dispensed with the normal stereo routing, we can now utilise six of the eight available aux sends as individual level controls to the six surround busses. To do this, click their On buttons, and select Master L, Master R, Rear L, Rear R, Cntr/LFE L, and Cntr/LFE R in their Send Routing pop-up windows.

You can now position any channel anywhere you wish within the surround environment, as well as sending low-frequency special effect material to the Sub channel. Since the aux sends are being used post-fader, the channel faders still provide overall level control for each sound, and channel level automation will still work well, although the channel pan controls are redundant. Of course, you'll have to have access to an external multi-channel recorder capable of receiving at least six inputs simultaneously on which to record your surround mixes.

This approach is perfectly usable (if somewhat fiddly) for setting up static surround mixes, and it's even possible to implement surround panning if you're prepared to record multiple automation passes of the aux send controls. Thankfully, although the full price of Nuendo is £799, Cubase users can upgrade for a much lower £579 if they want to throw in the towel and adopt a more elegant approach!

Steinberg Nuendo.In contrast to Cubase VST, Steinberg's Nuendo incorporated a particularly flexible implementation of surround sound right from version 1.0 (see screenshot below. You can define any number of output channels from two to eight in its VST Master Setup window, and then define their azimuth (angle) and radius (distance) settings. Presets are provided for stereo, quadraphonic, Standard 3/2 (similar to Dolby 5.1, but without the Sub channel), Dolby 5.1, 6.1, 7.1, and LRCS (Left/Right/Centre/Surround), and a graphic window shows how the surround channels are positioned.

Steinberg Nuendo.In contrast to Cubase VST, Steinberg's Nuendo incorporated a particularly flexible implementation of surround sound right from version 1.0 (see screenshot below. You can define any number of output channels from two to eight in its VST Master Setup window, and then define their azimuth (angle) and radius (distance) settings. Presets are provided for stereo, quadraphonic, Standard 3/2 (similar to Dolby 5.1, but without the Sub channel), Dolby 5.1, 6.1, 7.1, and LRCS (Left/Right/Centre/Surround), and a graphic window shows how the surround channels are positioned.

Once defined, the appropriate number of output meters appear in the mixer Master channel, along with a single master fader. Each channel in the mixer can then be routed either to any stereo output buss, any of the defined surround channels, or to surround pan. Selecting the latter replaces the normal panpot graphic with a surround pan plug-in whose pointer can either be moved with your mouse, or by any cheap PC analogue games joystick. For more precise control, double-clicking launches a much larger Panner window with further options, such as position or angle mode display.

You can export an audio file in 'Multi-channel Split' and 'Multi-channel Interleaved' formats, as well as mono and stereo modes, but Nuendo also includes Matrix Encoder and Decoder plug-ins for converting to and from LRCS format, and for Pro Logic-compatible encoding. Provisions are built in to let you apply effects plug-ins to various combinations of channels when mixing in any surround mode.

The optional Nuendo Surround Plug-in Pack will let you apply global effects such as compression, loudness maximising, seven-band parametric EQ, and reverb across up to eight channels simultaneously, to provide precise control over the final 3D mix, while its LFE Splitter lets you create a subwoofer channel from an existing mix. The LFE Combiner, on the other hand, integrates a separate subwoofer channel back into the other surround channels. TC Works have also released the impressive Surroundverb for Nuendo which uses technology based on their System 6000 hardware surround processor. Martin Walker

Emagic Logic

Logic handles surround in a very straightforward and intuitive way, the only requirement being a soundcard or audio interface with at least six output channels. From Logic's Audio menu, the Surround page provides the means to select any of the currently standard surround formats from stereo and quad (up to 7.1), with or without centre speaker, though the most common format is 5.1. This window shows which outputs carry which surround channels and also shows the file name extensions that will be given to any bounced or mixer surround files.

Emagic Logic.The next task is to set up a surround mixer in the Environment, which at its simplest means a number of channels with surround panners plus six outputs (I used two stereo and two mono) to carry the six components of the surround mix (the Centre and LFE outputs were fed through the mono outputs). The LFE or Sub channel would normally be low-pass filtered at 120Hz for film work, and in Logic, this is achieved by inserting a suitable low-pass filter plug-in into the LFE Output insert point (an 18dB-per-octave or third-order filter is good for this). Your monitor system is fed from your soundcard's outputs, so if these are also feeding a mastering recorder, some kind of signal-splitting and level control system may be required.

Emagic Logic.The next task is to set up a surround mixer in the Environment, which at its simplest means a number of channels with surround panners plus six outputs (I used two stereo and two mono) to carry the six components of the surround mix (the Centre and LFE outputs were fed through the mono outputs). The LFE or Sub channel would normally be low-pass filtered at 120Hz for film work, and in Logic, this is achieved by inserting a suitable low-pass filter plug-in into the LFE Output insert point (an 18dB-per-octave or third-order filter is good for this). Your monitor system is fed from your soundcard's outputs, so if these are also feeding a mastering recorder, some kind of signal-splitting and level control system may be required.

Your individual mixer channels are first set to surround mode as shown in the screenshot above, then, by double-clicking on the surround pan control, a larger pan window opens (visible above the Mid and LFE faders) where a pull-down menu allows the user to pick the required surround format for the channel (I used 5.1 for all channels, but with the no-centre option selected for channel 7 and 8 — I'll tell you why in just a moment). By moving the virtual surround pan control (much like a joystick), the signal is distributed between the five surround channels, while an LFE control at the bottom of the surround panner window sends a proportion of the channel signal to the LFE/Sub output (6). If you need more control over what signals appears (or not) in the centre channel, you can set up the individual channels for no centre speaker, then configure a post-fade Aux to send any desired amount of the channel signal directly to the Centre output (5) via a Buss. This would allow the contribution of the centre speaker to be adjusted manually for each channel, independently of the surround pan control setting. In my screenshot, the last couple of channels have been set up in this way, the centre signal being routed to Output 5 via Buss 1. Note that as Buss outputs are stereo, the pan control is used to steer the signal to Output 5 only.

While controlling and mixing surround within Logic is easy, there's always the question of how to deal with external sources, such as MIDI controlled hardware instruments. The best solution is to record these sources as audio back into Logic. Once recorded into Logic, they may be treated as any other audio tracks and positioned within the surround environment accordingly. Similarly, virtual instruments behave in exactly the same way as audio tracks as far as surround is concerned.

Once a surround mix has been set up (and automated if required), it can be bounced to a new set of mixed files, which in the case of surround means six discrete audio files labelled as in the first Logic screenshot bottom left. These may then be reloaded into Logic for playback or imported into a suitable surround editing/authoring package ready for transfer to surround media such as DVD-A or DTS. It avoids complications if the sample rate of the original recording matches that of the intended delivery medium and that the recording bit-depth is equal to or greater than that of the final format. Paul White

Surround-compatible I/O For The PC

A degree of confusion surrounds the issue (pun not intended) of suitable I/O hardware for PC users keen to try surround work, but suitable products do exist. Although Creative Labs' SB Live! has built-in DSP algorithms with surround capability, and does provide separate front and rear outputs, it doesn't let you access these separately from within a music application, so you can't use it for surround mixing — only for listening to specially encoded surround effects in games, for instance.

However, Creative's new Audigy soundcard does provide individual access to its Front L/R, Rear L/R, and Centre/LFE outputs when using its ASIO drivers, so you can use these to create a Dolby 5.1 audio mix. The card also has a built-in decoder to listen to existing Dolby 5.1 mixes. Terratec's DMX 6Fire soundcard (reviewed elsewhere in this issue) also helps the budding surround-sound musician, since its Control Panel utility provides a handy global fader controlling its Front L/R, Rear L/R, and Centre/LFE outputs. Creamware's Luna II is yet another soundcard that provides special surround features — this time a 16‑channel surround mixer — but you have to mix all your songs within its environment, rather than using your main sequencer application. Martin Walker

MOTU Digital Performer

When MOTU set about adding surround mixing to Digital Performer they weren't messing around. The implementation in DP3 is superb — easy to set up and highly flexible. What's more, DP's Mix Mode facilities make converting stereo mixes to surround (and vice versa) straightforward.

The key to DP3's surround flexibility is the Audio Bundles window, which at first glance doesn't appear to have an awful lot to do with surround. But it's here, under the Output tab, that you can select and configure output 'bundles' ranging from mono and stereo, through LCRS, Quad and 5.1, right up to 10.2 format (!). Once these bundles are set up (and this can be done on a project-specific or global basis) they're available as output assignments in normal mono and stereo tracks.

The type of bundle you select for an individual track determines what panner is assigned to it in the Mixing Board. Select a mono bundle and you get no panner at all; stereo, and you get a conventional pan pot. If you select any bundle greater than stereo, though, a surround panner appears, with a representation of speaker placement, and an indicator running around the outside showing spread between the speakers. This Mixing Board panner is just the tip of the iceberg, though. Click the little button next to it and you open one of four 'specialist' panners that allow much more accurate imaging control. You can switch between these at any time, and every track can have its own type of panner.

Arc Panner is like a magnified version of the Mixing Board panner and additionally provides an image focus control. n-Panner is effectively two pan pots combined — one each for left/right and front/rear — and again it has a focus control. TriPan is similar except that it offers a 'three knob' mode which allows signals to be very easily panned in straight lines around the surround field. It also offers full control over divergence — the extent to which signals panned to one speaker 'bleed' into the others. Amongst other things, this lets you exclude the Centre channel from general imaging duties, freeing it up for use by other tracks. All these panners offer flexible stereo placement modes along with configurable low- and high-pass filters which help to manage the frequency content of the LFE channel.

The remaining panner, Auralizer, is a little different. Basically it combines surround panning with a fine-sounding reverb, and adds doppler effects and psychoacoustic processing for good measure. Used well, it's a jaw-dropper, and can create wonderfully believable cathedral-size simulations as well as unnerving 'fly buzzing around your head' effects!

DP3 has some plug-ins dedicated solely to surround mixing, such as Calibration, which invites you to feed it the output of an omni-directional mic placed at your listening position before proceeding to play a range of tones that are used to automatically balance the output levels of your monitor speakers. Then there's Bass Manager, which is dedicated to keeping the LFE channel under control and can help to prepare mixes for home theatre systems which lack dedicated subwoofers. There are also surround versions of many of the standard MAS plug-ins, including the superb Delay (shown bottom right), which offers separate delay and feedback parameters for each channel, and eVerb, which can handle any number of input and output channels that you want to throw at it.

Finally, DP3 makes provision for surround tracks, so you could, for example, bounce down your 5.1 mix to a single six-channel track on which you've placed the surround edition of the MasterWorks Limiter plug-in. Additionally, multi-channel tracks really facilitate editing, archiving and distribution of final surround mixes. Robin Bigwood

Digidesign Pro Tools

Purpose-built surround mixing came to Pro Tools Mix systems with the release of software version 5.1 — a happy concidence in the numbering scheme! Prior to this, many Pro Tools mix engineers involved in film and DVD production used the standard kludges for using a stereo mixer as detailed earlier in this series, and owners of systems that pre-date Pro Tools Mix still have to employ these (more on this in a moment). Two significant things set Pro Tools Mix and the new HD systems apart and make them fully-fledged surround mixing environments: the ability to set up multi-channel busses, and surround panners.

Digidesign Pro Tools I/O Setup for stereo pairs.As on the other MIDI + Audio sequencers mentioned in this article, the variety of playback formats now available (from mono to 7.1) demands that the fundamental architecture of the mixer be flexible. In order to achieve this, Digidesign created the I/O Setup page. While most hardware mixers are hard-wired to provide mono and stereo input channels, and stereo mix busses (such as control room, group, and aux mix busses), I/O Setup allows you to configure your routing options from scratch. This can include a variety of inputs, inserts, output busses, and internal busses, which are anything up to eight channels 'wide'. It's easier to understand how this works by looking at something more familiar, so the screenshot shows the template for a normal stereo output structure in a Pro Tools system with eight audio interface channels. A graphical grid system maps the stereo mix busses on the left (which Pro Tools calls 'Paths') to the available physical outputs along the top. The paths declared in I/O Setup appear as destinations in the mixer, available to any track's output or aux send sections. In addition to these four stereo paths, we could also set up mono paths, linked to single outputs. With a routing template like this (probably the most common in use), if you wanted to route a mono track to, say, output 1, you could either set its output directly to 'A1', or set the output to 'A1-2' and set the stereo panner fully to the left.

Digidesign Pro Tools I/O Setup for stereo pairs.As on the other MIDI + Audio sequencers mentioned in this article, the variety of playback formats now available (from mono to 7.1) demands that the fundamental architecture of the mixer be flexible. In order to achieve this, Digidesign created the I/O Setup page. While most hardware mixers are hard-wired to provide mono and stereo input channels, and stereo mix busses (such as control room, group, and aux mix busses), I/O Setup allows you to configure your routing options from scratch. This can include a variety of inputs, inserts, output busses, and internal busses, which are anything up to eight channels 'wide'. It's easier to understand how this works by looking at something more familiar, so the screenshot shows the template for a normal stereo output structure in a Pro Tools system with eight audio interface channels. A graphical grid system maps the stereo mix busses on the left (which Pro Tools calls 'Paths') to the available physical outputs along the top. The paths declared in I/O Setup appear as destinations in the mixer, available to any track's output or aux send sections. In addition to these four stereo paths, we could also set up mono paths, linked to single outputs. With a routing template like this (probably the most common in use), if you wanted to route a mono track to, say, output 1, you could either set its output directly to 'A1', or set the output to 'A1-2' and set the stereo panner fully to the left.

The  Pro Tools' new Surround routing capabilities in the I/O Setup.are just an extension of these ideas. The screenshot top right shows a well-specified output set up for use in the 5.1 format. There are two main paths: a six-channel path (5.1) mapped to outputs 1-6, and a stereo path using up the two remaining outputs. There are also a number of sub-paths, mapped to various relevant output groupings, such as Left/Right only. If you wanted to place a track in the Centre speaker, you could just set its output to Centre, but what if you need to place it in between the Left and Centre, or have it spread out across the whole front wall? This is where surround panners come in, and the track would be given one automatically if you set its output to Full 5.1. On a 5.1 panner, the green dot represents the position of the sound in the mix, while the blue square indicates its 'width' or 'spread'. Additional controls serve to feed the Sub, and attenuate the Centre channel.

Pro Tools' new Surround routing capabilities in the I/O Setup.are just an extension of these ideas. The screenshot top right shows a well-specified output set up for use in the 5.1 format. There are two main paths: a six-channel path (5.1) mapped to outputs 1-6, and a stereo path using up the two remaining outputs. There are also a number of sub-paths, mapped to various relevant output groupings, such as Left/Right only. If you wanted to place a track in the Centre speaker, you could just set its output to Centre, but what if you need to place it in between the Left and Centre, or have it spread out across the whole front wall? This is where surround panners come in, and the track would be given one automatically if you set its output to Full 5.1. On a 5.1 panner, the green dot represents the position of the sound in the mix, while the blue square indicates its 'width' or 'spread'. Additional controls serve to feed the Sub, and attenuate the Centre channel.

As mentioned earlier, people with Pro Tools 24 and host-based systems built on Pro Tools LE as don't have access to these nice new surround facilities, but there are plenty of workarounds, such as that described by Martin Walker earlier in this article for Cubase. Space precludes me going into too much detail here, but my Pro Tools Notes column in SOS November 2001 tackles the subject in full. In summary, as in Cubase as described earlier, a combination of a track's main output and aux sends must be used for surround placement. For example, a vocal track might have its main output going to the centre, with a send feeding the Left and Right speakers to widen it. This works fine, although it's not as convenient as a surround panner, and it's difficult to achieve moving pan effects. Pro Tools 24 systems have a considerable advantage over host-based systems running Pro Tools LE, in that the former can run two third-party plug-ins which solve the problem. Smart Pan Pro, from Kind Of Loud, and the Dolby Surround plug-ins use clever behind-the-scenes trickery to provide surround panners. They both take a signal and distribute it to more than one of the existing stereo busses, achieving the same effect as the built-in panners in Mix or HD systems. Simon Price

Final Words

And that brings us to the end of SOS's series on surround sound, although we'll be returning to the topic at some point in the future for some practical advice articles.

At the time of writing, although it seems clear that some form of surround is here to stay, the most important format for audio production remains stereo, and most recording gear is still designed with that in mind. Whether this balance will shift over the coming couple of years, or whether surround sound will merely continue to exist alongside stereo production as a specialist format is far from certain, even now. Arguments continue to rage over the best format for presenting surround, from the optimum number of speakers to the best playback medium, which makes choosing 'future-proof' surround gear a risky business at present. Nevertheless, one of the aims of this series was to show that if you are interested in working in surround, it's possible to attempt it without throwing away your entire studio and re-equipping from scratch — and hopefully, we've achieved that.

Surround Sound Explained: Part 1 Foundations

Surround Sound Explained: Part 2 Dolby Pro Logic

Surround Sound Explained: Part 3 Ambisonics

Surround Sound Explained: Part 4 5.1 Surround

Surround Sound Explained: Part 5 Metadata, Upmixing, Downmixing & The Centre Speaker

Surround Sound Explained: Part 6 Setting Up A Surround Recording System

Surround Sound Explained: Part 7 Mixing In Surround

Surround Sound Explained: Part 8 Surround Production

Surround Sound Explained: Part 9 Surround In Your DAW

Thursday, October 26, 2023

Wednesday, October 25, 2023

Cubase: Keyboard Shortcuts & Key Commands

The Key Commands window showing a user assignment of the 'Add Track' Audio Command.

The Key Commands window showing a user assignment of the 'Add Track' Audio Command.

While using keyboard shortcuts in a sequencer is nothing new, this month we explain how Cubase SX/SL takes the idea further, and look at Hans Zimmer's unique solution for accessing Key Commands in Cubase.

Although the mouse has arguably made computers easier to use, it isn't always the most efficient device for carrying out certain tasks, especially when you might have to navigate a large display that spans multiple monitors. For this reason, keyboard shortcuts have been popular since even the very early graphical user interfaces, allowing you to instantly access commands from a single key combination and develop efficient patterns of working for different tasks.

In Cubase, the handling of keyboard shortcuts (or Key Commands, in Cubase-speak) is very flexible, and almost any action in the application can be assigned to a Key Command. Unlike previous versions of Cubase, SX/SL doesn't allow you to assign Key Commands to MIDI events, but the extra functionality now provided in this area of the application more than makes up for it, and it isn't something I've personally missed since I began using SX.

Key Commands

The management of Key Commands is handled, unsurprisingly, by the Key Commands window, which is opened by selecting File/Key Commands. To make life easier, the Key Commands have been grouped into a list of Categories, and the Commands list always shows the Key Commands available in the currently selected Category. However, if you're not sure which category a Key Command might be listed under, you can use the search facility to help you.

To search for a Key Command, click 'Search' to open the Search Key Command window. Click the black text field at the top of the Search window, type in a keyword and press Return — don't click 'OK' just yet, as this closes the window without performing the search. If your search was successful, you should see a list of matches describing the Key Command, the Category it's listed in and the keyboard shortcut that triggers the Command, if a shortcut has been assigned. Unfortunately, the Search Key Commands window is just a reference tool and you can't use it to automatically jump to a Key Command.

Once you've selected a Command in the Key Commands window, any assigned keyboard shortcuts for it will be detailed in the Keys list, so if the list remains empty, you can deduce that the Key Command is currently unassigned. To assign a Key Command, make sure the one you want to assign is selected, click the text field underneath the 'Type New Key Command' label and press a key (or combination of keys) on your keyboard. If the key (or keys) you pressed is already assigned, the Key Command it's assigned to will be displayed underneath the text field. Should this happen, try another combination.

When you have a unique keyboard shortcut entered, click the Assign button to assign the Key Command, and you'll notice that it appears in the Keys list. You can remove an assignment from the Keys list by selecting it and clicking 'Remove'. You'll then have to confirm, in the Alert that appears, that you really do want to remove the assignment, by clicking 'Remove' once more.

Many of the available Key Commands are unassigned by default. Perhaps the most commonly used Commands just crying out to be assigned are the Add Track Commands. However, it's interesting to note that some of the unassigned Key Commands can't be accessed in any other way than by assigning them. These include useful features such as the nudge Commands, which allow you to nudge the current selection by the current quantize setting.

Key Command assignments are Project-independent and stored within Cubase SX itself, meaning that any Key Commands you assign will be available to any Project you open or create. If you want to use your assignments on another system, you can save them by clicking the Export button in the Key Commands window, and reload them via the Import button. Steinberg supply many Key Command sets with Cubase, to emulate the way keyboard shortcuts are assigned in other applications, such as Logic, Sonar, and earlier versions of Cubase. Windows users can find these in the 'Program Files/Steinberg/Cubase S?/Key Commands' folder, while Mac users will find them in the 'Library/Application Support/Steinberg/Cubase S?/key commands' folder.

Macro Madness

While Key Commands are useful, Cubase SX/SL takes the idea one step further by implementing Macros, making it possible to define a sequence of Key Commands that can be triggered via a single command from the Edit/Macros sub-menu. And, naturally, you can also trigger a Macro with a Key Command, since any Macros you define automatically appear in the Macros category of the Key Commands window.

The Key Commands window again, showing the Macro options with a recreation of the 'Loop Selection' Command.A good example of what's possible with Macros is the Loop Selection Command in the Transport menu (while this is not strictly a Macro, it does demonstrate the kind of command that can be defined with one). If you're not familiar with Loop Selection, it sets the Left and Right Locators based on the current selection, positions the Project Cursor at the Left Locator, activates Cycle Mode and starts the Project playing — all in a single Command that can also be triggered by pressing [Shift]-[G]. But let's pretend that the Loop Selection Command doesn't exist for a moment and investigate how we could create it using a Macro.

The Key Commands window again, showing the Macro options with a recreation of the 'Loop Selection' Command.A good example of what's possible with Macros is the Loop Selection Command in the Transport menu (while this is not strictly a Macro, it does demonstrate the kind of command that can be defined with one). If you're not familiar with Loop Selection, it sets the Left and Right Locators based on the current selection, positions the Project Cursor at the Left Locator, activates Cycle Mode and starts the Project playing — all in a single Command that can also be triggered by pressing [Shift]-[G]. But let's pretend that the Loop Selection Command doesn't exist for a moment and investigate how we could create it using a Macro.

As mentioned above, Macros are handled in the Key Commands window, and although the Macro options are hidden by default, you can access them by clicking the Show Macros button. To create a Macro, click the Create Macro button, type a suitable name into the highlighted space in the Macro list, and press Return. The next step is to add the Commands you want the Macro to trigger, which you can do by selecting the Macro you want to add the Command to in the Macros list, selecting the required Command in the upper part of the window and clicking 'Add Command'. It's important to note that the Command is always added below the currently selected item in the lower Commands list, and that there's no way to change the order in which the Commands are triggered after they've been added, unless you manually remove them and start again. You can remove a Command from the Macro by selecting it in the lower Commands list and clicking 'Remove Command'.

To recreate Loop Selection, you'd need to add the following Commands from the Transport category to a Macro, in this order: Locators to Selection, To Left Locator, Cycle, and Start. Once a Macro has been defined, you can assign a Key Command to it in the upper part of the window, or simply close the Key Commands window by clicking OK. Macros can be triggered by either pressing the assigned Key Command, or selecting them from the Edit/Macros sub-menu.

Conclusions

It will be interesting to see if Macro functionality is enhanced in future versions of Cubase, but, even as it stands right now, there are plenty of interesting uses for Macros. For example, you could define a Macro that created Hitpoints and audio slices in a single keystroke, or a series of quantize buttons, such as 'quantize quarter notes' or 'quantize eighth notes' that select a quantize resolution and quantize the current selection — and this is just scratching the surface. If you come up with any interesting Macros, email them to us, at sos.feedback@sospubs.co.uk, so that they can be featured in future Cubase Notes columns.

Key Commands & Control Surfaces

If you use a hardware control surface with Cubase that supports user-assignable function keys, you should be able to assign Key Commands to them in the Device Setup window. This works really well with control surfaces such as the Mackie Control, for example. This unit has eight function keys that, with the aid of a shift key, can provide access to 16 Key Commands. However, Mackie Control also supports two footswitches that can also be assigned Key Commands, and I've found it really useful to assign these to Start/Stop and Return To Zero, in the Transport, for example.

Burger, Fries & Transpose The Selection

This month, I've been fortunate enough to spend some time at Media Ventures in California looking at Cubase SX with Hans Zimmer, who's probably the world's most experienced Cubase user, in addition to being one of its greatest film composers. Over the years, he's developed an incredibly efficient working method with Cubase, and one aspect of this is based around the concept that it should be possible to trigger every action with a Key Command. Inspired by the keypads used on cash registers in fast-food restaurants, where keys are assigned to different foods and beverages, Hans and his team came up with a really neat way of accessing Key Commands in Cubase, using the same type of keypad.

The model in question is the Electrone KM128A, which provides a 16x8 matrix of 128 user-definable keys that can be assigned to any combination of standard keyboard actions. Devices like the KM128A behave just like regular keyboards and have no problem co-existing with such keyboards, interfacing with your computer via a PS2, USB (with the aid of a PS2-to-USB adaptor) or serial connection. Unfortunately, a Windows PC with a serial or PS2 interface is required to program the keypad, since the supplied software is only compatible with Windows and doesn't support USB, although, once programmed, you can also use the keypad with a Mac.

During keypad programming, each key is assigned a unique combination of keys that you would never hit by accident on a normal QWERTY keyboard, and that wouldn't already be assigned to a Key Command, such as 'Control/Apple+Shift+{'. So when you're assigning Key Commands, you simply press the required key on the keypad, which Cubase interprets as a regular combination of keys on a standard keyboard. Afterwards, as you'd expect, you can press the same key on the keypad to trigger the Key Command in Cubase — pretty neat.

So which Cubase Key Commands does Hans assign to his keypad? This is where things get interesting. Since most of the commands Hans wanted to assign to his keypad couldn't be assigned as Key Commands in Cubase VST, the team turned to CE Software's QuickKeys, which allowed them to create both relatively simple menu-based shortcuts, to trigger Logical Editor presets, and more complicated macro-based solutions.

Although you can now create Macros in Cubase itself, you still can't assign Key Commands for Logical Editor presets. Another feature you'd still have to use QuickKeys for in SX/SL is Hans' row of keys for switching the data displayed by the Controller Lane in the Key Editor. Being able to switch between volume, pan and modulation data, amongst others, with a single keypress is particularly useful — so useful, in fact, that Steinberg are considering adding this ability directly via built-in Key Commands in future versions.

If you're interested in getting one of these keypads, at £265.55 in the UK (from www.intolect.com) their cost is fairly high, although you might be able to apply the same ideas to cheaper alternatives. QuickKeys is available as an online download, at www.cesoft.com. It costs $79.95 and comes in three different versions, for Mac OS 9.x, Mac OSX and Windows.

Tuesday, October 24, 2023

Monday, October 23, 2023

Cubase's Logical Editor Window

The Logical Editor window is a powerful way to process MIDI data in Cubase, although it can often appear daunting to new users. What's more, it provides excuses for writers to dust off their Mr Spock quotes...

The Logical Editor window has been part of Cubase since the days when musicians wrote on four-line staves with the blood of wild boars, and while it remains the most powerful off-line MIDI processing tool in SX/SL, the appearance and operation of the Logical Editor window itself has undergone major surgery during its journey from Cubase VST. The original (or should that be 'classic'?) Logical Editor window was covered in the December 2000 and January 2001 Cubase Notes columns, so this month we're boldly going into the unexplored world of SX/SL's Logical Editor. Before we get started, though, I just want to stress that the idea of this column is to provide a basic overview of the Logical Editor window, as it would be impossible to cover every single facet in a two-page article. However, we'll return to some more advanced uses of the Logical Editor window in future Cubase Notes.

Illogical, Captain?

Although the Logical Editor can often look rather unfriendly, its operation really is quite, well... logical, once you get the hang of it. The basic operation of the Logical Editor window is to specify conditions in what's known as the Filter Condition List (in the upper part of the window) that will select certain MIDI Events to be processed according to instructions specified in the Action List (in the lower part of the window). A simple example of this would be to take a melody that pivoted around middle 'C' where you wanted to transpose every instance of this note up an octave, leaving the other notes intact. In the Logical Editor window you would use the Filter Condition List to select only the middle 'C' notes and the Action List to transpose the selected notes up an octave.

While it sounds obvious, in order to be able to open the Logical Editor window, you need to have some MIDI Events available to be processed, whether they've been recorded, entered manually, or imported from a MIDI file. As with the standard MIDI processing Functions, the Logical Editor window can be opened to process all of the Events in the selected MIDI Part (or Parts) on the Project window, all the Events in the Editor window you're currently using, or only the selected Events in the current Editor window. So, assuming you have some MIDI Events to process, to open the Logical Editor window simply select MIDI / Logical Editor.

To get a basic overview of using the Logical Editor window, let's start by implementing the simple 'transpose only the middle 'C' notes up an octave' example. The default function of the Logical Editor window, where the Events selected by the Filter Condition List are transformed by the Action List, is known rather appropriately as Transform. The fact the Logical Editor window is set to the Transform function is indicated by the pop-up menu at the top left of the window — you can select other Logical Editor functions from this pop-up menu, which we'll look at later on.

The Filter Condition List

The first step is to set the Filter Condition List to select all the middle 'C' notes, and, as the name implies, the Filter Condition List is made up of a sequence of lines that set the conditions for the Events we want to process. By default, the Filter Condition List will probably contain one line when you open the Logical Editor window — if it doesn't (or to add extra lines later on), simply click the upper Add Line button to the right of the Filter Condition List. As you might expect, if you need to delete a line if there are too many or you want to start again, simply click the upper Delete Line button, which will delete the selected line in the Filter Condition List.

Each line in the list is broken down into a number of columns to define the instruction, and the Filter Condition List is summarised as a statement in the black box just underneath the list in the Logical Editor window. Once you get a feel for the way Filter Condition Statements are written, you can also click this box to edit the statement manually.

In order to set the Filter Condition List to find notes that are middle 'C', we actually need two lines: the first line to say 'find notes', and the second to specify that the only notes we're interested in are those where the pitch is middle 'C'. For the first line, Filter Target should be set to Type Is — to set the various elements for each line, simply click in the line under the appropriate column heading and choose the required parameter from the pop-up menu. Staying on the first line, Condition should be set to Equal, and Parameter 1 should be set to Note. After you've done this, notice how the Filter Condition Statement reads 'Type = Note'.

You'll probably need to click Add Line to add another line to the Filter Condition List, and in this second line Filter Target should be Value 1 since pitch is always the first parameter in a note event — and notice how the Logical Editor window displays Pitch as the Filter Target, rather than Value 1, to confirm this. As an aside, the second parameter in a note event is velocity, so if you wanted to find notes of specific velocities you could set Filter Target to Value 2. However, getting back to the second line of this example, Condition should again be set to Equal, and Parameter 1 should be set to the pitch of the notes we want to find, middle 'C'.

Unfortunately, the Logical Editor window isn't clever enough yet to let us set the pitch in terms of a useful value such as C3 (middle 'C') — instead, we have to know what the required pitch is as a MIDI note number. Fortunately, MIDI note numbers are easy to work out if you remember that middle 'C' is 60 and each value is worth a semitone; so the 'C' an octave below middle 'C' would be 48, while the 'D' above middle 'C' would be 62, and so on. So in this case, Parameter 2 on the second line should be set to 60.

The Filter Condition is now complete and you should see the finished statement as 'Type = Note And Value1 = 60' in the Filter Condition Statement. Now the Logical Editor window knows what we're looking for, we can proceed to tell it what to do with the MIDI Events once it finds them.

The Action List

The Action List is similar in operation to the Filter Condition List, and so is also based on a series of lines (which are again summarised by an Action Statement in a black box just below the list that can also be edited) that specify what is to happen to the Events found by the Filter Condition List. In our example, we want to transpose the found Events up an octave, so if there isn't already a line in the Action List, click the Add Line button — the lower one that's next to the Action List this time, though. Again, you can also remove the selected line by clicking the associated Delete Line button.

The first column in an Action line is the Action Target, which is the parameter of the Event we want to process. Since we want to change the pitch of the selected notes, the Action Target should be Value 1 — remember Value 1 is always holds the pitch information for note events. The Operation column specifies what we actually want to do with the Action Target — in this case, since we want to transpose the notes upwards, the Operation should be Add. Finally, in this example, Parameter 1 specifies how much we want to add to the pitch of the selected notes (in semitones) — as we're transposing up an octave, Parameter 1 should be set to 12. And that's all there is to it.

Once the Filter Conditions and Actions have been programmed, carrying out the process on the selected MIDI Part on MIDI Events is a simple matter of clicking the Do It button. And, rather brilliantly, because the Logical Editor window is displayed in a 'floating' window, you don't have to close it to carry on working or select other MIDI Parts and Events for processing. In fact, you can undo the Logical Editor processing, make a different selection of Events and carry out the processing again all without having to close the Logical Editor window.

Logical Editor Presets

If you program a process in the Logical Editor that you'd like to use again without having to enter it from scratch again, you can save it (along with a brief text description in the Comment field) as a preset by clicking the Store button in the Presets group at the bottom right of the Logical Editor window. Cubase will prompt you for a name, and when you press Return, your preset will be added to the list of Logical Editor presets available from the pop-up menu in the Presets group in the Logical Editor window. Logical Editor presets can also be executed without using the Logical Editor window by selecting the MIDI Events you want to process and choosing the required Logical Editor preset from the MIDI / Logical Presets pop-up menu. It's worth noting that Logical Editor presets are not tied to any one particular Project, so any preset you create is always available in Cubase no matter what Project you're working on.

You can run Logical Editor presets without having to actually open the window by selecting them from the MIDI / Logical Presets sub-menu.

You can run Logical Editor presets without having to actually open the window by selecting them from the MIDI / Logical Presets sub-menu.

If you want to overwrite an existing preset, simply select the preset, make the required changes, click the Store button again, type in the exact same name as the preset you want to overwrite and press Return — Cubase will ask you if you really want to overwrite the preset, so click Overwrite. You can remove Logical Editor presets by recalling them from the Preset pop-up menu in the Logical Editor window and clicking the Remove button. Rather worryingly, Cubase doesn't check if you really do want to remove the preset and the operation can't be undone either, so make sure you're certain that you no longer need it.

In the first release of SX/SL for Mac OS X (1.04), Cubase seemed a little confused about where to look for and save user presets for Project Templates, plug-ins, and, of course, the Logical Editor window. However, fortunately this has been solved in the latest version (1.0.52), and Cubasenow always looks for and saves Logical Editor presets in the 'Home/Library/Application Support/Steinberg/Cubase S?/Presets/Logical Edit' folder, where Home is the name of your user account. Windows users never had to worry about where Cubase was looking for and saving Logical Edit presets, as this was always the 'Program Files/Steinberg/Cubase S?/x' folder. Now you know where these presets are stored, of course, you can also create subfolders to organise your presets, which are translated into sub-menus in Cubase.

Cubase Tips

- Pressing Shift+P, Shift+L or Shift+R opens a text field on the Transport Panel so you can edit the location of either the Project Cursor or the Left or Right Locators numerically — just like pressing P, L or R in Cubase VST. Unlike Cubase VST, however, once highlighted, only one of the four parts of the numerical location can be edited at a time — you need to press the left and right cursor keys to switch to other parts. If the Transport Panel is closed when you press one of these shortcuts, it will be automatically opened for you, although, unfortunately, it also remains open after you press Return.

- Staying with the theme of handy keyboard shortcuts, you can toggle the display of certain parts of the Project window via Key Commands. Press Control/Apple+I for the Event Infoline, Alt/Option+I for the Inspector, and Alt/Option+O for the Overview.