Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions. Where there are no limits! Enjoy your visit!

Welcome to No Limit Sound Productions

| Company Founded | 2005 |

|---|

| Overview | Our services include Sound Engineering, Audio Post-Production, System Upgrades and Equipment Consulting. |

|---|---|

| Mission | Our mission is to provide excellent quality and service to our customers. We do customized service. |

Tuesday, February 28, 2023

Monday, February 27, 2023

Project Templates

Cubase comes with a number of preset project templates... but it's probably better to roll your own.

Cubase comes with a number of preset project templates... but it's probably better to roll your own.

We've all experienced the frustration of having the brilliant germ of an idea slowly drain away as we get our recording software organised with all the inputs, outputs, tracks, effects and virtual instruments we need to capture it. You might not even remember what 'it' was by the time you've reached the point where you're ready to hit record.

Creating your own project templates is one of those useful housekeeping jobs you can do when you're in a less creative mood. You'll reap the rewards when your mood changes, because a well thought‑out project template will enable you to get up and running in a single click. In Cubase 5, when you select File / New Project, the Project Assistant provides you with a number of preset templates, but good though some of these may be for newbies, it's better to roll your own — because that way, you'll end up with something that's properly tailored to your specific needs.

So what should and what shouldn't you include in a project template? A good template should be pre‑loaded with all the essentials you're likely to need in a project, but should also enable you to get up and running quickly and easily — and that's not always an easy balance to strike. The template needs to be free from all those unnecessary extras that make a project cumbersome to use, and you need to avoid packing it with anything that means the template takes an age to load, or, if you're planning to do any low‑latency monitoring, or play virtual instrument parts in via MIDI, anything that increases latency.

If the type of projects you do varies (I might do anything from a sole acoustic musician to a full, programmed orchestral score, for example), it's probably also a good idea to create a series of different templates, each fine‑tuned to the requirements of these different recording and mixing tasks.

Ins & Outs

Make sure you have the various input and output channels of your audio interface specified within the VST Connections dialogue box before starting work on your Project Template.

Make sure you have the various input and output channels of your audio interface specified within the VST Connections dialogue box before starting work on your Project Template.

As a starting point, select the 'Empty' template project from the Project Assistant's 'More' tab. By default, this template contains nothing aside from any input and output channels that you have already configured in the Devices / VST Connections dialogue box. So it's worth making sure that you have the various ins and outs of your audio interface suitably labelled and activated (via Devices / Device Setup), so that they appear in the mixer window of any new project. This is particularly useful if you have a large number of input channels and use them in a consistent fashion (a group of inputs used for a drum-kit setup is one example). In fact, if you tend to change audio interface setups regularly, or if you have different standard microphone setups for certain tasks, you can create dedicated templates specifically for the I/O configuration in this box, via the Presets drop-down menu.

On The Buses

With a colour coded Folder and a Group Channel for each major instrument group, you can keep your project organised right from the start.

With a colour coded Folder and a Group Channel for each major instrument group, you can keep your project organised right from the start.

With the I/O sorted, we could start creating a series of audio and MIDI tracks... but to keep things organised, and make the creative process easier when inspiration strikes, I prefer to start 'backwards', by creating a suitable set of group and folder tracks. How many of these you require, and how you use them, will vary according to the type of project you're creating a template for. For example, with a standard rock band you might set up a separate group track for each of the drums, bass, rhythm guitars, keyboards, lead/solo instruments, lead vocals and backing vocals. Alternatively, for basic orchestral work you might require groups for strings, woodwind, brass, keyboards/harps and percussion, although you could obviously make this more sophisticated with, for example, subgroup channels for the different string sections, all feeding the 'master' string‑section group).

The big advantage of using group channels is that those broad‑brush mixing tasks, where you're establishing the overall balance between the key instrument groups in your project, become much easier to manage and automate: you can mute, solo or apply effects to these channels, as well as creating a custom Mixer window to show only the group tracks.

Keeping Track

A series of tracks (in this case, just audio tracks) can be pre‑configured within each folder track.

A series of tracks (in this case, just audio tracks) can be pre‑configured within each folder track.

Having created the group tracks, I like to organise the tracks that form each group into folder tracks — perhaps even putting the groups into the relevant folder too. That way, you can open up a folder when you need to do work on the elements within a group (for example, recording or balancing the various rhythm guitar tracks or backing vocal tracks) but, if required, can hide all the other tracks to avoid distractions, and keep everything easy to navigate.

In each folder, I've found it useful to create a number of empty tracks, so I can get started recording as soon as the template is opened for a new project. You might not want to create dozens of empty tracks, as that defeats the object of keeping things simple, but half a dozen or so makes for a good start. Unless I know I'm only going to need one track type, I find that a mixture of audio and MIDI tracks in each folder is best. I also tend to include a combination of mono and stereo audio tracks, for maximum flexibility.

Although this might seem like I'm adding potentially unecessary elements, by approaching the template in this way I can include some suitable generic track names ('Rhythm Gtr 1', 'Rhythm Gtr 2' and so on), which can be a time-consuming process that you don't want to have to do again and again with each new project. Not only will naming make project navigation easier, but it will also mean that any audio recorded on those channels will be appropriately named (there's nothing worse than trawling through lots of files called audio_01 and so on!).

For audio tracks and VST instruments, an important final step is to make sure the output of each track is set to the appropriate Group channel, rather than the main stereo output.

Bells & Whistles

Make sure the main output (or outputs) from any included VST instrument are routed to the appropriate Group Channel.

Make sure the main output (or outputs) from any included VST instrument are routed to the appropriate Group Channel.

It's difficult to pre‑configure software instrument sounds to cover every eventuality, but it's worth including anything you commonly use. Depending on the style of music, this might include, say, an acoustic piano, your favourite drum tool, or basic ensemble patches for each of the major sections of an orchestra.

However, while it might be tempting to stuff your template full of the biggest and best sample‑based instruments, this isn't the best approach: if you do, the project will take an age to fire up, while you wait for all the sample layers to load. It's much better to keep things simple: for composition purposes, for example, a basic 'working' patch is probably all you require to get started. If you tend to automate certain parameters of an instrument (say, the filter cutoff and resonance of your favourite synth), it might be worth adding automation lanes for those parameters.

Just For Effect

![]() Including some of your favourite Insert effects on each Group Channel (in this case compression and tube emulation) is also useful.

Including some of your favourite Insert effects on each Group Channel (in this case compression and tube emulation) is also useful.

It can be be useful to add some send effects to your template, although, again, it's best to keep things simple. The obvious choices would be two effects channels containing a basic reverb and a delay, but, as I hinted earlier, try to avoid anything that will add to the system's latency. If you like to use a convolution reverb in your mixes, for example, you might be better off using an algorithmic one for recording, and substituting it later in the project for mixing duties — and the same goes for any DSP effects from the likes of the UAD or TC Powercore cards. Sends to your effects from each of your main group channels, or any key individual tracks like the lead vocal, can also be assigned, so that if you need a bit of reverb to add to your initial rhythm guitars or guide vocal, it's ready and waiting to go.

You don't need to stop there: if you like a little transparent compression across most of your major instrument groups, just add suitable compressors as insert effects on each of your group channels. Similarly, when working on pop and rock material I regularly apply a touch of tube emulation to each of my instrument groups, so I've created a template that pre‑loads my favourite tube and tape emulation plug‑ins.

The simple guide here is that anything you have found yourself regularly using in previous sessions can be added to your template for speed of access, even if you leave it switched off in the first instance — but try not to overdo it, or you'll probably put yourself off using the template!

What Else?

There is a range of other useful things you might do to customise a project template for your needs. Colour‑coding your tracks according to their instrument group can help to provide a useful visual cue when you're browsing through a complex project. Personally, I also like to add ruler, arranger and marker tracks to my templates, as I tend to use them a lot. It can also be useful to customise your initial window layout, as this will be recalled when the template is opened: for example, you might customise your transport panel to show only the key features you regularly use.

The final step, of course, is to save your new project template via the File / Save As Template menu option. Next time the creative spirit happens to drop by, your shiny new (and hopefully perfect) project template will be waiting for you under the 'More' tab of the Project Assistant.

Published October 2010

Saturday, February 25, 2023

Friday, February 24, 2023

Level Meters

Knowing how to interpret and act on Cubase's level meters can help you to make better mixes.

Cubase allows you to change the appearance and behaviour of its meters.

Cubase allows you to change the appearance and behaviour of its meters.

Every DAW package worthy of the name includes digital peak meters, whether in a mixer, on individual channels or both — but how often do you actually use them for anything more than an animated red and green light show? Paying more attention to your meters — and looking beyond simply where they 'clip' — can lead to better mixes.

When I say 'clip', Cubase doesn't actually clip the signal during processing: its 32- or 64-bit engine can accommodate much higher levels. But when you bounce any processing down to 24-bit (or maybe 16-bit) files, or when the signal passes through any A-D or D-A conversion stages (if you're using external effects, for example), the audio file can't store all that information — and you'll end up with clipping. It's this I have in mind when talking about clipping in this article.

In Cubase 5, the channel level‑meters are digital peak meters: they show you how near to clipping the highest peaks of each track are, and if they clip, there's a 'virtual‑LED' indicator at the bottom of the meter that will remain red — an indication that you should pull things back a bit. They're tweakable to some extent, as I'll explain later, and setting them up so you know what they're telling you is important.

But however you calibrate them, such meters tell you very little about how 'loud' things are. Even the briefest, inaudible transient can clip without you really noticing, and it may be that the average level is actually quite low. In other words, you could have two channels, both with the same meter reading, but one much louder than the other; or one signal only reaching ‑20dBFS and the other reaching 0dBFS, but the ‑20 one actually sounding louder! To monitor loudness, you need a different sort of meter that works on average levels — a VU or PPM meter. Cubase doesn't include such meters, but it's easy enough to add third‑party plug‑ins to do the job (I'll discuss a few options later).

You also need to know where any meter is taking its reading from: is it at the channel input, before all the insert slots, after the inserts, or after the fader? It makes a huge difference!

A final thing to say about peak meters in general is that they're quite a blunt tool and won't always tell you if a signal is going to clip. It's perfectly possible for there to be material that doesn't register as clipping on a conventional peak meter, yet will distort when run through a D‑A converter, as the converter 'draws' the the peak of the curve represented by the digital audio signal.

In this article, I'm going to run through a few strategies for getting the best out of Cubase's built-in level meters, and will recommend a few free or inexpensive plug‑ins that can help you plug the gaps where Cubase falls short.

The Built-in Meters

Who needs to see red, unless they're approaching clipping? By changing the colours and calibrating Cubase's meters as shown in the previous screen, I'm easily able to see when a signal reaches ‑18dBFS, as well as when it clips.

Who needs to see red, unless they're approaching clipping? By changing the colours and calibrating Cubase's meters as shown in the previous screen, I'm easily able to see when a signal reaches ‑18dBFS, as well as when it clips.

By default, Cubase's meters are set to show the input level on each channel. This can be changed by right‑clicking on any fader, at which point you're presented with the option to set all meters as pre‑ or post‑fader, or post‑pan. There's no option to do this individually for each meter; such an option could quickly become confusing, but it would be nice to be able to change the master and group channels independently, so you could monitor channel inputs and bus outputs, or vice‑versa. The pre‑fader option displays the input level before any processing; the post‑pan option displays the signal level after the inserts and pan 'pot', and post‑fader displays exactly what you'd expect. Each setting has its uses at different stages in the recording and mix processes.

Conventionally, with an analogue mixer, you'd monitor the channel inputs, to make sure the signal wasn't clipping on the way in, and set each processor so that the signal was at roughly unity gain. That way, you could patch things in and out without affecting the level, and would hear (or see on the group meters) if you were overcooking things: you wouldn't really need post‑fader channel metering. The stereo‑bus meter, though, would be set to post‑fader, so you could see what was going out of the desk.

It's a sensible approach to follow in Cubase, though I do find things slightly different in any modern DAW. For one thing, you probably can't see all your channel and bus meters at once — so it makes sense to display the channel levels post‑panner or post‑fader when mixing. That way, you know you're not overcooking things with processing before the signal goes to the fader, or from the fader to the bus. On the master bus, group or effects channels, I'll also want to know whether the signal is clipping on the way in, and will often rely on a dedicated meter on the last insert on the stereo bus to monitor the output level.

Colour & Calibration

Cubase lacks any VU or PPM‑style metering, and PSP Audioware's freeware Vintage Meter plug‑in can fill that gap.

Cubase lacks any VU or PPM‑style metering, and PSP Audioware's freeware Vintage Meter plug‑in can fill that gap.

All Cubase's level meters are presented as virtual‑plasma columns, with four different colours and a dedicated virtual clip LED. If you go to Cubase/Preferences/Appearance/Meters (Mac) or File/Preferences/Appearance/Meters (PC), you'll find the option to change any of the four colours, and to move the point at which the colours 'cross over'.

This isn't just an aesthetic option. For example, if you leave the 'turnover points' spaced apart, the transition between colours is quite gradual, getting redder (using the default colour scheme) as the signal gets hotter. If, instead, you pull them close together into pairs you can get a much clearer indication of when a certain (non‑peak) level has been reached. It's far from conventional, but I find that latter approach handy, because I can calibrate things so that I can easily set up individual drum tracks to peak no higher than around ‑12dB post‑fader, without having to look at the numeric values on each track. That way, I can be more confident that I'm leaving sufficient headroom on the drum bus, without having to scroll along a busy mixer and look at the bus itself.

Plug‑in Meters: Pay Attention!

Each channel in Cubase has an input gain control, a level fader and six pre‑fader and two post‑fader inserts. There are more opportunities than I'd care to count to push signals into clipping. So, with metering only available directly in Cubase at three points in the chain, it pays to look more closely at gain structure in your plug‑in chains.

The unity‑gain approach discussed earlier is a good practice to get into, but it's not the only way of working. Some manufacturers offer an input and output meter as standard on their plug‑ins, and these can help you to get a cleaner, more satisfactory result from your processing: the bottom line is that you shouldn't really be 'clipping' at any stage, because whereas analogue gear might distort in a muscially pleasing way, and while analogue‑modelling plug‑ins can imitate this behaviour, real digital clipping (unless used as a deliberate effect) will offend your ears.

If your plug‑ins don't include the necessary meters, try inserting Cubase's Compressor with the threshold set to maximum (so that it doesn't act on the audio), and use its meter: simply drag it around your project to the appropriate insert slot when you want to check levels.

Third‑party Metering Tools

Right‑clicking on a meter reveals options for selecting the point in the signal chain from which the meters take their readings.

Right‑clicking on a meter reveals options for selecting the point in the signal chain from which the meters take their readings.

As I mentioned, peak metering isn't the only form of metering. Some form of average‑level metering, such as a VU or PPM meter, will give you a much better indication of the relative loudness of different signals, because they're not measuring the full‑scale transients. So as long as you leave enough headroom to allow for those transients, the averaging meter is a much more useful mix tool. PSP Audioware's cross‑platform freeware Vintage Meter (www.pspaudioware.com/plugins/tools_and_meters/psp_vintagemeter) can be configured in much the same way you would an analogue meter.

When it comes to inter‑sample distortion, SSL offer another freeware meter called X‑ISM (www.solid‑state‑logic.com/music/x‑ism/index.asp), which simulates the process performed by a D‑A converter, and warns when the recreated analogue signal would go above 0dBFS, even though the digital peak‑meter would tell you that the signal remained within that limit.

There are many commercial offerings you could look at if you feel the need, from the likes of RNDigital and Waves, for example, but it's also worth looking at the range of other plug‑ins you already own: some of them include quite sophisticated metering options. For example, I use Universal Audio's Precision Limiter as often for metering as for its intended function as a limiter.

The Master Stereo Buss

The gain strategy I've described is similar to the one you'd use on an analogue console, and if you work in this way, you should find that you have plenty of headroom on the master channel, which means that you're able to bounce your mix, or any part of your project, without fear of clipping. You'll have plenty of scope to process the full mix during mastering. To work in this way, you should be aiming for an average level of something in the order of ‑18dBFS at the input stage on the master bus, and pretty much the same at the output stage — unless you're trying to do any mastering, or 'finalising' at this stage; usually, you wouldn't do that, as you need fresh ears for those tasks.

Nonetheless, you may sometimes find that your mix is clipping at the bus‑input stage, and Cubase gives you a few options for handling this. First, you could reduce the level of all the channels feeding the bus — but, whichever way you choose to do this, it's a faff once you've started to use automation, or threshold‑sensitive processing on groups or effects channels. Alternatively, you can use the input trim control at the top of the bus to attenuate the signal before any processing. Given the floating-point processing, that's a perfectly acceptable approach — though unecessary if you get the levels right in the first place! Finally, you can use the input gain of the first insert plug‑in on the bus to attenuate the signal, which is essentially the same thing. Also, don't forget the advice I've already given about monitoring the input and output levels of your insert plug‑ins, because this applies as much to your master‑bus plug‑ins as it does to any others.

But It's So Quiet!

If you're used to running everything very hot and start to work in the way I've described, you may find that things seem to be rather quiet — and thus less impressive than usual. The remedy is to turn up your amp or monitors, not to raise Cubase's faders! You can get the levels back during the mastering process, and a better mix will be the result.

Meters can only help you so much, and there's really no substitute for using your ears — but the meters in Cubase are there for a reason, and it pays to understand what they and any other meters are telling you: not only can they help you avoid the undesirable sound of digital clipping, but they really can help you to create a better mix of any track.

Published November 2010

Thursday, February 23, 2023

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

MIDI Controllers

Even a handful of knobs and sliders on a MIDI master keyboard are enough to give you hands‑on control of your Cubase mix.

If you just want to make use of some faders and knobs on your MIDI master keyboard, the Generic Remote is the controller you need to select.

If you just want to make use of some faders and knobs on your MIDI master keyboard, the Generic Remote is the controller you need to select.

If you want to mix in Cubase using physical faders, but can't afford, or don't have the space for, a dedicated hardware controller, the faders and knobs built into many MIDI master keyboards offer a capable, low‑cost alternative. In this article, I'll explain how to mix in Cubase using your master keyboard's controls.

For the purposes of illustration, let's assume we have a basic MIDI master keyboard that includes eight faders and eight rotary knobs. The most obvious way to exploit these controls for general mixing duties would be to assign them to volume and pan for a series of eight tracks in your Cubase project. So, assuming your keyboard is already connected to a suitable MIDI port for MIDI note entry, how do we configure these hardware controls for mixing duties in Cubase?

Remote Places

The upper table in the Generic Remote dialogue tells Cubase what controls your surface has, while the lower lets you assign these to mix parameters.

The upper table in the Generic Remote dialogue tells Cubase what controls your surface has, while the lower lets you assign these to mix parameters.

The first step is to get Cubase to recognise your keyboard as a remote control device, using the Remote Devices section of the Device Setup dialogue (accessed via the Devices menu). Clicking on the '+' button at the top left of the window opens a list of dedicated hardware controllers that Cubase supports, such as the Mackie Control. We require the 'Generic Remote', and once clicked, this is added as an item underneath the Remote Devices folder. When this is then selected, the centre‑right section of the Device Setup dialogue changes to show a range of default settings.

For most standard MIDI master keyboards, you'll need to specify the MIDI input (in my system, TC Near via my TC Electronic audio and MIDI interface) but can safely leave the MIDI output as 'not connected'. All this means is that Cubase will not be sending MIDI data back to the keyboard (which is not necessary unless your controller features motorised faders or some form of visual feedback). The bulk of the display is dominated by two tables. The upper table is used to define what controllers your hardware surface has. By default, it includes a combination of faders, knobs, mutes and sends. This is fully editable, and it makes sense to adjust the list so that it only contains entries suitable for the actual physical controls you have on your hardware surface — that's eight faders and eight knobs in this example. As you edit the upper table, the lower table changes to display the same list of controls.

Clicking on any entry in the lower table (in this case, the Value/Action column for fader 1), brings up a list of the possible assignments.The lower table is used to map a specific hardware control to a specific parameter in Cubase. This can be almost anything from a track fader to a particular effects parameter, but some care is needed, as these controls are 'fixed' to that single parameter until you return to the Device Setup dialogue to change them. The flexibility is considerable, but there is not much point is assigning controls to an effects processor that might not be used in your next project, so for a basic mixing setup the obvious candidates are volume and pan for some mixer channels. The question is which mixer channels?

Clicking on any entry in the lower table (in this case, the Value/Action column for fader 1), brings up a list of the possible assignments.The lower table is used to map a specific hardware control to a specific parameter in Cubase. This can be almost anything from a track fader to a particular effects parameter, but some care is needed, as these controls are 'fixed' to that single parameter until you return to the Device Setup dialogue to change them. The flexibility is considerable, but there is not much point is assigning controls to an effects processor that might not be used in your next project, so for a basic mixing setup the obvious candidates are volume and pan for some mixer channels. The question is which mixer channels?

If, as described in SOS March 2008, you tend to submix your various audio and VSTi tracks to a series of group channels, these make a good target. In this example, I have eight group channels in the project (drums, bass, keyboards, lead vocals, backing vocals, rhythms guitars, lead instruments and a catch‑all called 'other'). As shown in the screenshot, clicking in the Device, Channel/Category, Value/Action or Flags column for any of the controllers in the list produces a list of options that can be assigned. In this case, I've assigned each of the eight faders to control volume of one of the group channels in the VST Mixer.

Learn Control

In the second 'bank', the eight faders and knobs have been assigned to volume and pan for the first eight audio tracks.

In the second 'bank', the eight faders and knobs have been assigned to volume and pan for the first eight audio tracks.

The second stage is to link each of your hardware controls to Cubase, using the Learn button, which makes the process very straightforward: simply select a control in the list contained in the upper table (for example, Fader 1), move the appropriate fader or knob on your hardware surface and then press the Learn button. The hardware controller is then linked to that virtual controller and, via the entry in the lower table, to a specific parameter in Cubase. You then simply repeat this process for each of the controls on your keyboard.

Bank Interest

While eight faders may be better than none, if you want to do more than mix a set of group channels, you'll need to use the four 'banks' of controls offered in the Generic Remote configuration. As shown in the screenshot above, the alternative banks can be accessed via the small drop‑down list. In this example, I've configured the three other banks to provide volume and pan control for a series of 24 audio channels, but other targets, such as VSTi outputs, are possible.

Once this configuration is complete, if you open the (tiny!) Generic Remote window (from the Devices menu, as shown in the screenshot, right), you can toggle between the four banks as required – in this case giving us control over four banks of eight channels (the bank of eight group channels, and three banks of eight audio channels). Hey presto! You now have hands‑on control of a key part of the mixing process. Combine this with recording your fader movements as automation data (a topic for a different column) and those complex mixes can suddenly seem to be much more manageable!

Project Translation

The tiny Generic Remote window allows you to switch your hardware device to control multiple banks of parameters. As described in the main text, the Generic Remote configuration is sensitive to the Track List order. Here, the eight group channels are followed by 24 audio tracks. Also note the Quick Control on/off button in the Inspector pane — which is useful for disengaging the Quick Control system when required.

The tiny Generic Remote window allows you to switch your hardware device to control multiple banks of parameters. As described in the main text, the Generic Remote configuration is sensitive to the Track List order. Here, the eight group channels are followed by 24 audio tracks. Also note the Quick Control on/off button in the Inspector pane — which is useful for disengaging the Quick Control system when required.

The Generic Remote settings are global in nature: once configured, the settings apply to every project. This has positives (you don't have to repeat the configuration process from scratch for each project) and negatives (not all your projects will require the same configuration). The approach also has a number of quirks, perhaps the most significant of which is that it is sensitive to the order in which tracks are placed in the Track List of the Project window.

Consider the example used above where the eight group channels happen to appear at the top of the Track List. If, for instance, an audio track were to be added above these group tracks, it would bump down all the hardware controller assignments by one. Fader 1 of bank 1 would now control this audio track, rather than the first of the group channels. At first, this can cause some confusion, but once you are aware what's happening, it's easy to work around the problem: it simply requires a consistent approach to ordering your tracks in the Track List. I often place group channels at the top, followed by audio tracks. The latter can be put into folders if required; it's the overall track order that's important.

Thankfully, the Generic Remote configuration options include import and export buttons. If you do need to configure your hardware controls in different ways for different project types, these can be saved and subsequently recalled, allowing you to develop any number of different configurations as required.

Generic Remote, Or Quick Controls?

Whereas a Generic Remote setup is most suited to mixing operations, the Quick Control system (SOS July 2009) is targeted at hardware control of individual tracks, with up to eight parameters in the currently selected track capable of being tweaked via a hardware controller. The two systems therefore complement each other very well.

One quirk is that it is possible to have both systems operational at the same time, and thus have the same hardware control linked to two different and unrelated parameters in Cubase. If you are not careful, you might find yourself inadvertently changing two parameters with one controller movement! Thankfully, the Quick Control system can easily be disabled via the Quick Control panel of the Inspector, allowing you to use your Generic Remote configuration. The most straightforward way to temporarily disable the Generic Remote system while you use Quick Control is to open the Generic Remote dialogue box from the Device Setup window, and then deactivate the MIDI input to the Generic Remote. Although this approach may be a little clumsy, it does at least do the job.

Published December 2010

Tuesday, February 21, 2023

Monday, February 20, 2023

Switching To 64-bit?

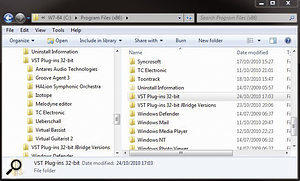

It's well worth creating your own folder structure for 32‑bit plug‑ins, especially if you intend to use the third-party jBridge rather than Cubase's own VST Bridge.

It's well worth creating your own folder structure for 32‑bit plug‑ins, especially if you intend to use the third-party jBridge rather than Cubase's own VST Bridge.

If you're a Cubase user still working in the 32‑bit world, but interested in what the 64‑bit version of your DAW has to offer, is it now time to make the move? Robin Vincent discussed some of the potential advantages and pitfalls of moving to a 64‑bit OS in SOS November 2010, but in an attempt to answer that question for you in a Cubase-specific way, I'll share a few tips and pointers from my own recent experience of this process. While this is very much a PC‑based view, there should be plenty that is of interest to Mac‑based Cubase users too.

Be A Good Boy Scout

Moving from 32‑bit to 64‑bit can involve a considerable amount of software installation work, and it pays to 'be prepared' before you start — so make sure you have all the necessary install disks, serial numbers and update patches to hand, and you should also be checking for 64‑bit availability of all your key effects and virtual instrument plug‑ins.

For those currently using a 32‑bit OS (as I was, with Windows 7), the first significant question is whether to retain the existing 32‑bit OS and create a second partition for your 64‑bit OS (multi‑booting between the two) or to replace the 32‑bit OS partition with a 64‑bit one. Note that Windows 7 doesn't allow an install of the 64‑bit version over the top of the 32‑bit one: Windows 7 64‑bit requires a 'clean' install. My experience of the multi‑boot options built into Windows 7 is that they're pretty robust, so if hard-drive space allows, I'd suggest keeping your tried and trusted 32‑bit environment and build your 64‑bit equivalent in a second partition — or you could install it on a separate physical drive if you prefer. Better safe than sorry!

Martin Walker has covered creation of new partitions and multi‑booting a number of times in SOS (see our web site for past articles), but it's worth adding one minor tip: while the Windows 7 boot management seems to operate well, you might consider a third‑party application to tweak its settings. There are a number of free and shareware applications available that can make life a little easier. I use EasyBCD from NeoSmart (www.neosmart.net).

Make A List

If you use a custom folder structure, make sure the correct paths are listed in Cubase via the Devices / Plug‑In Information / VST 2.x Plug‑In Paths dialogue box.

If you use a custom folder structure, make sure the correct paths are listed in Cubase via the Devices / Plug‑In Information / VST 2.x Plug‑In Paths dialogue box.

Most of us run plenty of software alongside Cubase: my own checklist consists of Steinberg's Halion 3, Groove Agent 3, Halion Symphonic Orchestra and Virtual Guitarist 2, Sony Acid Pro 7 (via Rewire), NI Komplete, Ueberschall's Liquid Instrument and Elastik plug‑ins, Toontrack's Superior Drummer 2, Antares' Autotune Evo and Celemony's Melodyne.

Of this key list, many of the Komplete plug‑ins are now 64‑bit, while Halion 3, HSO and SD2 are also 64‑bit. The others, at the time of writing, were only available as 32‑bit plug‑ins. In principle, this shouldn't pose problems, because built into Cubase 64‑bit is VST Bridge, which is designed to allow 32‑bit plug‑ins to communicate with Cubase 64‑bit. In practice, though, some users have still encountered problems (search the Steinberg forums and you'll soon find some examples). I'll return to this point later.

If this is your first step into the world of 64‑bit music making, the common‑sense approach would definitely be 'keep it simple'. To that end, having installed the 64‑bit OS (and done all the necessary updates and security patches), you should then install just your audio drivers and the 64‑bit version of Cubase 5, plus any updates necessary to get you to the latest version (v5.5.1 in this case). Now it's time for some thorough testing: the key issue is likely to be how robust your 64‑bit audio drivers are, so stretch the system as hard as you can using just Cubase 5 and its built‑in plug‑ins.

Mix & Match

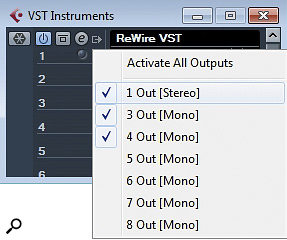

Rewire VST: a neat way to provide Rewire functionality in the 64‑bit version of Cubase.

Rewire VST: a neat way to provide Rewire functionality in the 64‑bit version of Cubase.

As mentioned above, it's possible to mix and match 32‑bit and 64‑bit plug‑ins in Cubase 64‑bit. Lots of 32‑bit applications will also work quite happily in a 64‑bit OS, and this includes the 32‑bit version of Cubase. It's perfectly possible to have both the 32‑bit and 64‑bit versions installed together, meaning that you can have the 32‑bit version available if you do have a key plug‑in or two that won't play ball in the 64‑bit version. Plug‑in compatibilities aside, projects can be moved between the 64-bit and 32‑bit versions quite happily.

Windows 7 puts all the 64‑bit applications in the usual Programs folder and also creates a Programs (x86) folder for any 32‑bit applications, but a little extra care and user intervention can be required when installing plug‑ins. For example, plug‑ins that have both 64‑bit and 32‑bit versions will get placed into suitable VST plug-in folders under both the Programs and Programs (x86) folders. While keeping the 32 and 64‑bit versions well away from one another is a good thing, the default locations used by the various installers may not be optimal. It therefore makes sense to install all your third-party effects and instrument plug‑ins into a folder structure of your own choice.

This is particularly useful if, as described by Robin Vincent, you intend to use the very popular jBridge alongside (or instead of) Steinberg's own VST Bridge. jBridge is a good investment (about €15 from http://jstuff.wordpress.com/jbridge/) and seems to deal with some plug‑ins much better than VST Bridge. However, 32‑bit plug‑ins have to be 'scanned' by the jBridger utility to create a bridging file, and it is the folder containing the bridging file that has to exist as a VST plug‑in path in Cubase. While there are various ways you might organise your 32‑bit plug‑ins, I simply created two folders under the Programs (x86) folder: one named 'VST Plug‑ins 32‑bit' and a second named 'VST Plug‑ins 32‑bit jBridge versions'. When installing my third-party 32‑bit plug‑ins, I made sure they all went into the first of these (with subfolders for plug‑ins from different manufacturers), and the bridging files created by jBridger into the second.

Usefully, jBridge also supports bridging of 64‑bit plug‑ins in a 32‑bit host. If your original plug‑ins and jBridge versions (both 32-bit and 64‑bit) are well organised, in principle, at least, you ought to be able to switch seamlessly between 32‑bit and 64‑bit versions of Cubase, with access to your plug‑ins in both hosts.

For my own part, I was very happy to find that my key instrument and effects plug‑ins listed above worked fine in Cubase 5.5.1, VST Bridge dealing with the 32‑bit ones. While installing and testing one plug‑in at a time may take longer than installing everything in one go, I think it's a less painful experience than doing a mass installation and then having to unpick things later as you discover problems.

Rewire Is Dead, Long Live Rewire!

Rewire VST allows one stereo and six mono audio channels to be returned from your Rewired client.

Rewire VST allows one stereo and six mono audio channels to be returned from your Rewired client.

One of my main reservations about moving to 64‑bit was the loss of Rewire support — but thankfully there's a third‑party solution in EnergyXT's Rewire VST (www.energy‑xt.com). This virtual instrument can be added to a Cubase project in the usual way, and allows you to 'Rewire' another application via the plug‑in. While only one instance of Rewire VST can operate at a time, it does support the transfer of one stereo and six mono audio channels from the Rewire client back into Cubase, and allows the Cubase transport and tempo to control the client.

On my PC system, this worked a treat with Acid Pro, and compared with using the built‑in Rewire support of Cubase 32‑bit, the only significant difference was that I couldn't also use the Acid transport controls to stop and start playback of the two sync'ed applications. That's a shame, but it's not a deal breaker, especially as Rewire VST only costs around £20.

Finally….

I did have difficulties with one 32‑bit plug‑in in this process: Melodyne Editor. In one sense, I wasn't too surprised, because although Melodyne is one of my favourite pieces of audio software, I'd already struggled with it on my 32‑bit OS. I'd pretty much accepted that the rather unpredictable performance was due to some software/driver conflict specific to my system. However, Celemony had announced that a 64‑bit version was 'coming soon' and, two days before I actually starting writing this column, v1.2 of Melodyne Editor, which includes 64‑bit support, became available. I've only had time for some brief experiments, but so far the performance has been flawless: I am a man with a smile!

Bearing in mind some of the problems I'd heard about from other users concerning the transition from 32-bit to 64‑bit operation — mostly seeming to focus on certain combinations of plug‑ins — I started my own experiments with some trepidation. While I wouldn't suggest that my fairly painless experience will be shared by everyone, I am at least encouraged by how smooth, albeit time‑consuming, the process turned out to be. I'm glad I didn't take the jump six months ago, but I'm equally glad that I now have. You should make the change cautiously, check forums for other users reporting difficulties concerning your own key plug‑ins, and leave yourself a 32‑bit bolt‑hole if things don't pan out but, personally, I think the 64‑bit environment is now mature enough to deliver on its potential.

Published January 2011